Ecclesiastical Law and the Church of England

Alexandra Fairclough

In 1997, the Secretary of State for Culture Media and Sports commissioned the Newman Report, A Review of the Ecclesiastical Exemption from Listed Building Control. Many of the issues raised by John Newman in his report have been addressed in the Faculty Jurisdiction Rules 2001, which came into force on 1 January 2001. These changes include changes in nomenclature, new consultation procedures for listed buildings and revised documentation. This article seeks to provide an overview of the Church of England’s faculty system and an update of the recent changes.

WHAT IS ECCLESISTICAL EXEMPTION?

All churches are subject to planning law, and planning permission is required for operational development or change of use regardless of denomination or faith. However, church buildings of certain denominations enjoy exemption from listed building consent and conservation area consent. This exemption originates from the Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act 1913. Since 1913 this has included ecclesiastical buildings that are, ‘for the time being, used for ecclesiastical purposes’.[1]

The Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport may restrict or exclude by order certain buildings or categories of buildings from the exemption. Since 1994 the exemption has applied only to those denominations that have created an ‘approved system of control’. Currently, this exemption applies to the Church of England, the Church in Wales, the Roman Catholic Church, Baptist Union Church, Methodist Church and the United Reformed Church. Other denominations do not fall within the exemption and full listed building or conservation area controls apply. Similarly, other faiths such as Judaism and Islam also fall within secular control.

PLANNING CONTROL AND THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND

The Church of England’s system of planning control, which was recognised by the Secretary of State, is governed by canon law, ecclesiastical law and heritage law. As these laws and canons form part of this country’s ordinary legislation, they require the sanction of Parliament before coming into force.

In addition to the requirement for planning permission, works to all Church of England buildings (whether listed or not) have been controlled for many centuries by the Consistory Courts of the Church. The faculty system is a judicial system now governed by primary legislation (The Care of Churches and Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction Measure 1991), secondary legislation (The Faculty Jurisdiction Rules SI 1992 No 2882 and SI 1992 No 2884) and a code of practice (The Care of Churches and Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction Measure Code of Practice 1993).

Under the provisions of the Care of Churches and Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction Measure 1991, all works, alterations and additions to parish churches, their churchyards and contents require faculty approval.[2] This legal requirement applies to consecrated buildings and land and other churches licensed for public worship since 1 March 1993.

A faculty is a permissive right to undertake works to a church building or its contents. It is the duty of the minister and churchwardens to obtain a faculty before carrying out any alterations subject to the de minimis list (see below) provided by each diocese. Works undertaken without a faculty are illegal even though a retrospective confirmatory faculty may legitimise unauthorised works, and any person undertaking works without a faculty may be liable to both civil procedures (in effect for ‘trespass to land and goods’) and criminal procedures (the Criminal Damage Act applies). A parochial church council (PCC) would also be in breach of trust and a minister may also face disciplinary proceedings.

This system has a far wider remit than the existing secular control as the scope extends to all places of worship irrespective of their heritage status. These include parish churches and other non-parochial structures such as institutional chapels. Legally, ownership of a church is generally vested in the incumbent and held on trust by the PCC for the parishioners, while the contents are the distinct responsibility of the churchwardens who hold them on trust for the parishioners. However, final control over the church, contents and land rests with the chancellor of the diocese, acting on behalf of the bishop.

Once consecrated by the bishop (usually by a special consecration service), a building may not be used in a manner that does not respect its sanctity. A statutory duty is placed on any person or body undertaking the care and conservation of a church building in that they must have ‘due regard to the role of the church as a local centre of worship and mission’ (although this duty does not apply to a chancellor of the diocese when adjudicating a faculty petition), and all liturgical matters should be classed as a material consideration (see paragraph 8.12 PPG15 and para 143 Welsh Office Circular 61/96).

In relation to the Church of England the exemption[3] applies to the following:

- any church building within the faculty jurisdiction

- any object or structure within such a building

- any object or structure attached to the exterior of the building

- any object or structure within the curtilage of such a church building although not fixed to the building. However, the exemption does not apply to an object or structure attached to the building or within the curtilage if it is independently listed.

DE MINIMIS WORKS

The de minimis list includes works or items of a minor nature and as such do not require a faculty. The chancellor agrees the list after consultation with the diocesan advisory committee and others. The exemption from faculty usually includes the following works:

- maintenance and cleaning of churchyards

- introduction or removal of moveable items

- the repair and maintenance of certain areas of church fabric and boundary walls so long as the appearance and structure is not affected and the costs are minimal.

The PCC, minister and/or churchwardens should seek the advice of the registrar or the secretary to the diocesan advisory committee to assess whether the works fall within the de minimis provision. This provision is usually agreed subject to conditions such as the use of a quinquennial inspector or other suitably qualified professional; the approval of English Heritage or the Heritage Lottery fund if financial assistance has been given; and a recommendation in writing by the local planning authority that planning permission or building regulations is not required.

APPLYING FOR A FACULTY

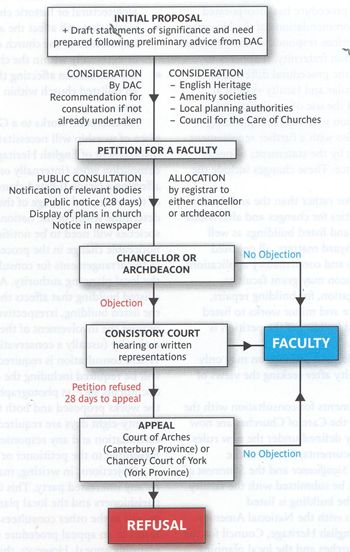

The chart below depicts the proper procedure that a petitioner (or applicant) for faculty should adopt following the new Faculty Jurisdiction Rules.[4] This flowchart refers to schemes involving a material alteration to a building. Most straightforward applications relating to repairs bypass the consultation process and do not require press advertisements. The archdeacons do not have delegated powers to deal with cases involving material changes or churchyard applications even if they are unopposed. The type of cases dealt with by the archdeacons is tightly defined – mainly repairs, maintenance and minor alterations such as the replacement of an altar cloth.

Every diocese has a diocesan advisory committee (DAC) for the care of churches. It comprises of a chairman, the archdeacons and not less than 12 other members. The archdeacon, a person of more than six years holy orders, assists in the faculty procedure. The diocesan bishop appoints him or her and the role is pastoral, administrative and quasijudicial. The archdeacon has the authority to grant unopposed faculty petitions for unlisted churches.

| Who's Who | |

| LEVEL | LEGAL ENTITY |

| Provincial - 2 provinces in England (Canterbury and York), each with an archbishop | The Court of Arches (Canterbury) and The Chancery Court (York) - hears appeals |

| Diocesan - 44 diocese in England and 6 in Wales: 24 senior bishops with at least one diocesan bishop per diocese - suffragan bishops | Consistory

courts (one per diocese) - mainly hears objections Chancellors - up to one diocese, but some chancellors appointed to several dioceses. Chancellors decide the more complex faculty petitions on the advice of the DACs. Archdeacons - several per diocese, each responsible for several parishes. Archdeacons decide the less complex faculty petitions. Diocesan advisory committees (DACs) - one per diocese |

| Parish - 13,150 parishes in England and Wales with 16,000 churches (13,000 of them listed) | Incumbents - usually a vicar (one per parish) - responsible for the buildings Churchwardens - at least two per church Parochial church councils (PCC) - representing the congregation of each church |

The other members include two persons appointed by the Bishops’ Council and, of the other ten, three are approved by each of the following: the Joint Committee of the National Amenity Societies, English Heritage and the Local Government Association. The intention is that the DAC must have access to a good knowledge of the history, development and use of the church buildings; a good knowledge of the art, architecture and archaeology of the artefacts, buildings and churchyards; and a good knowledge of the care and conservation of historic buildings and their contents as well as of liturgy and worship. The bishop may also approve other appointments to act as consultants to the DAC if the DAC so requests.

The functions of the DAC are set out in Schedule 2 of the Care of Churches Ecclesiastical Jurisdiction Measure 1991.[5] They are briefly:

- to act as an advisory body on matters affecting places of worship in the diocese and in particular advise the bishop, chancellor, archdeacons, PCCs and any applicants for faculties on related matters including architecture, archaeology and the history of the place of worship; the use, care and design of places of worship including redundancy; and the use and care of the church, its contents and its churchyard

- to assess the risk of loss or damage to archaeological or historic remains from any proposals to petitions for faculties

- create a repository record for all proposals to alter, conserve and repair

- to approve the appointments of all quinquennial inspectors for the care and conservation of church buildings.

The faculty procedure has incorporated many of the recommendations of the Newman Report and therefore responds to the concerns of the conservation fraternity. It appears to have addressed the procedural differences between the secular and faculty system at least in terms of the use of specialist advice, in the consultation with the local planning authority and also with a further requirement of a justification by the statements of needs and of significance. These changes include the following:

- the chancellor rather than the archdeacon grants faculties for changes and alterations to unlisted and listed buildings as well as all churchyard matters, all opposed applications and confirmatory applications. The archdeacon may grant faculties, under delegation, for building repairs, maintenance and minor works to listed and unlisted building if the petition is unopposed.

- the chancellor and archdeacon may only grant a faculty after seeking the views of the DAC

- the arrangements for consultation with the Council for the Care of Churches are now more tightly defined under the new rules

- two new documents, known as the Statement of Significance and the Statement of Needs, must be submitted with the faculty petition if the building is listed

- consultation with the National Amenity Societies, English Heritage, Council for the Care of Churches and the local planning of Churches and the local planning authority is required at an early stage

- the period for display of public notices has been extended to 28 days for all faculty petitions.

All applicants for faculties must seek the informal advice of the DAC. This is advised to be at the earliest opportunity. Indeed, on proposed schemes which involve changes to a building, parishes are encouraged to consult the DAC informally at an early stage.

Formal advice must be sought of the DAC in all petitions for a faculty. The intending applicant should submit plans, elevations, the statements of significance and need (if a listed building) and a specification for the works. The Statement of Significance should include as much information on the quality of the building as possible. This includes a copy of the listing. The Statement of Needs, which should be provided by the minister, churchwardens and the PCC, should give the reasons why they consider that these changes are necessary to assist in worship and the church’s mission. These two documents are important tools for the petitioners and also for the parish architect, the DAC, English Heritage, the National Amenity Societies and the Local Planning Authority. The chancellor will also consider them. Petitioners for alterations relating to listed churches should submit their statements (of needs and significance) at the earliest opportunity.

Appendix B of the Faculty Jurisdiction Rules 2000 (SI No 2047)[6] outlines the criteria for consultation with the external bodies. It is likely that some consultation will be required if the works include any of the following:

- alteration or extension to a listed church where the works would affect the special architectural or historic character

- works that will affect the archaeological importance of the church either internally or externally within the church curtilage

- any demolition affecting the exterior of an unlisted church within a conservation area.

All alteration works to a Grade I or II* place of worship will necessitate the involvement of English Heritage as will any demolition work (internally or externally) affecting a Grade II listed church. The nature of the works and the age of the building will determine which of the national amenity societies will need to be notified. The most noticeable change in the procedures has been in the arrangements for consultation with the local planning authority. Any change to a listed building that affects the character of the listed building, irrespective of grade, will require the involvement of the local planning authority (usually a conservation officer). Where consultation is required, full details will be required including the designs, other documents such as photographs, details of the works proposed and both the statements. Twenty-eight days are required for the consultation and any responses should be forwarded to the petitioner or DAC.

Objections, in writing, may be made by any interested party. This includes parishioners and the local planning authority as well as the other consultees. This may result in an appeal procedure similar to a planning appeal. However, this is undertaken before the actual decision is made. The forms of objection are written representation and an oral hearing including cross-examination. The chancellor will sit in a consistory court hearing and will assess and analyse the evidence. The chancellor will present his judgement at the end of the hearing ex tempore or it may be reserved for a later date in writing.

The burden of proof lies with the petitioners. Arguably it is not easily discharged. Recent cases in the Court of Arches have imposed a higher test for petitioners to satisfy in listed buildings than the secular test in Planning Policy Guidance Note 15. The Consistory Courts follow a test of why? how?, and when?[7] In short, the test needs to address the following:

- have the petitioners proved a necessity for the proposed works?

- if yes, will the works adversely affect the character of a church as a building of special architectural and historic interest?

- if so, is the necessity such that in the exercise of the court’s discretion a faculty should be granted.[8]

Necessity has been interpreted as something less than essential but more than merely desirable or convenient. A heavy burden sits on those who wish to alter listed churches. In unlisted churches the approach is similar to that for listed buildings. Much depends on the nature, age and quality of the unlisted building. Generally, alterations are allowed unless there are grounds for refusal. Heritage issues are considered as reasonable grounds for refusal.

A statutory appeal exists to the Court of Arches in the Canterbury province and the Chancery Court of York in the York province. An application for appeal must be made on a point of law and the chancellor of either the Consistory Court or the provincial court (the Court of Arches or the Chancery Court) gives leave. The time limit is 28 days from judgement. The Dean of Arches or the Auditor of the Chancery Court (in fact the same person) determines these appeals with two diocesan chancellors presiding.

|

The new faculty rules have incorporated many of the issues of concern relating to heritage. This Parliament has allowed the faculty system to continue and any change to it would require a constitutional upheaval. The system predates the secular building control system by several centuries and the balancing argument remains in that the existing and future needs of liturgy and mission are powerful material considerations.

Religious worship and mission is at the heart of the argument here. However, it must always be remembered that churches are also national monuments and include many of the most important historic buildings in England and Wales. (Almost half our Grade I listed buildings are churches - 2,858 in total - and a further 2,900 are Grade II*).

The new consultation regime is welcomed and time will tell if the new rules are successful in ensuring early involvement of national heritage specialists. The remaining issues of concern relate to the lack of consistent policies or practical guidance. These may vary from diocese to diocese as it does from planning authority to planning authority. It is also argued that the system of decision-making is too private with no public access to meetings or files at the lower levels. This is perhaps justified by the facility to request an open hearing by any related objector. However, it must be noted that the new rules require that, in all schemes involving significant changes to listed buildings, a full set of plans should be on display in the church from the date of the petition’s submission to the determination of the application.

In truth it is the PCCs and petitioners that may suffer the most from a lack of clear guidance. These concerns may be shortlived as many of the dioceses have started to produce guidance notes and booklets to assist the petitioner in the faculty process. However, clear central guidance would be the most beneficial. The Council for the Care of Churches also has started to produce quality guidance that is now readily available on its website. The main issue here is that there are relatively few professionals who understand the system adequately enough to advise parishes. Hopefully, this overview of the system will help in this respect.

~~~

Notes

[1] S60 Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990

[2] www.hmso.gov.uk/measures/ukcm_ 19910001_en_7.htm

[3] Article 5 Ecclesiastical Exemption (listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Order 1994

[4] www.hmso.gov.uk/si/si2000/20002047.htm

[5] www.hmso.gov.uk/measures/Ukcm_ 19910001_en_7.htm#sdiv2

[6] www.hmso.gov.uk/si/si2000/ 20002047.htm#appb

[7] Re Emmanuel, Northwood (1998) 5 Ecc LJ 213, London Consistory Court, Chancellor Cameron

[8] Known as the Bishopgate questions adopted by the Court of Arches in Re St Luke the Evangelist, Maidstone 1995 Fam 1 and Re St Mary the Virgin Sherbourne 1996 Fam 63

Recommended Reading

- M Hill, Ecclesiastical Law, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2001

- M Hill, Heritage and Holiness, Paper presented to Jubilee International and Ecumenical Canon Law Conference at Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, USA, 2000

- C Mynors, Listed Buildings, Conservation Areas and Monuments, London, 1999