The Neues Museum

A fresh approach to conservation

Jonathan Taylor

|

|||

| A third of the Neues Museum was destroyed in the war, including its central staircase. The reconstruction captures some of the spirit of the ruin, with rough reclaimed brick walls, but the new stair and roof is unashamedly modern. (Photo: Dennis Gilbert) |

Design approaches to the conservation of historic buildings vary widely. One approach is to retain damaged fabric as if it had just been found, consolidating it, preserving it, but not restoring it to its original condition. Nowhere is this more dramatically illustrated than at the Neues Museum, Berlin where fine classical architecture has been frozen in a state of romantic deterioration, reminiscent of a drawing by the 18th century illustrator Piranesi.

The Neues Museum is part of a complex of magnificent neoclassical buildings on the northern part of an island in the river Spree at the heart of Berlin. Conceived as a cultural necropolis by the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm IV in the early 19th century, it is now known as Museuminsel. The first museum on the island was the Altes Museum, designed in a strict Grecian neo-classical style by the great Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel in 1830. The Neues Museum by Schinkel’s protégé, Friedrich August Stüler, came next and was completed in 1859. The last museum was not completed until 1930, just nine years before the outbreak of World War II.

The soft sandy soil of the river island posed a challenge for construction. By the time construction started on the Neues Museum, the single storey Altes Museum had already shown early signs of settlement, and this museum was to be much taller, with three storeys over a basement. It was therefore constructed as lightly as possible on timber piles. Stone floors were constructed on a base of shallow vaults of hollow terracotta pots between a grid of ironwork and supported by columns. While those of the principal spaces were of stone, the columns on the third floor were of iron, clad in cast zinc ornament to achieve the classical style required. The roof trusses were of cast iron with wrought iron ties and partly gilded.

The museum’s biggest attraction was its collection of ancient Egyptian artefacts, especially the head of Nefertiti. The Neues Museum was hit by incendiary bombs in 1943 gutting the central stair hall, the Treppenhalle, and in 1945 the museum was hit again, this time at the south-east end, gutting further parts of the building. In addition to damage from the ensuing fires, the cooling effect of the fire hoses used to quell the fire caused much of the structural cast iron work to shatter.

|

|

||||

| Above left: the south-west front of the Neues Museum showing the post war devastation and, above right, the elevation as seen from the Spree today. The facade to the left was reconstructed without its classical ornamentation. | |||||

For the next 50 years the building

languished. Not only was it bombed out,

with much of it roofless, but the building had also suffered from differential settlement,

weakening the shallow terracotta vaults.

Funding was scarce in post-war Germany,

particularly in East Germany, and in any

case there were more pressing problems such

as housing the thousands left homeless. It

was not until the 1980s that a significant

stabilisation programme was launched to

enable the building’s restoration. By then

it was found to have sunk around half a

metre into the soft ground. Before it could

be underpinned with a concrete raft, the

superstructure had to be surveyed and

then repaired and reinforced. During this

process much more of the surviving plaster

and decorative finishes were removed.

The predominant approach taken in Germany during the post-war period was to rebuild what was lost, faithfully copying the original to recreate the country they had known before, as at Potsdam. There was no reason to suppose then that any other approach would be likely to be followed here. As a result the repairs carried out in the 1980s replaced the original soft 19th-century brickwork with hard bright red engineering bricks and cement-rich mortars, ready to be covered over with a render in future restorations.

|

||

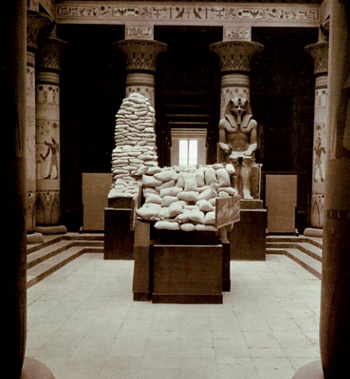

| The Egyptian hall during the war with protective sandbags around artefacts (Reproduced by kind permission of Zentralarchiv der SMB) |

The museum’s future took a dramatic turn for the better when, in 1990, it found itself once again at the heart of a reunified Germany, and in the hands of a more prosperous administration.

By this time it was considered that approximately two thirds of the Neues Museum had survived, but much of this had been reduced to bare structure, and only about a third of its original fine decorative finishes remained intact.

An international competition was held to appoint a designer for the ‘reconstruction’ of the museum in 1993. Although it was won by the Italian firm of Georgio Grassi, the commission was eventually passed to the runners up, the British firm of David Chipperfield Architects. DCA had by then established an international reputation for its innovative museum and gallery designs, but lacking in-house conservation expertise DCA brought in Julian Harrap Architects as consultants. The two practices had worked closely in the past and JHA’s work on the Soane Museum, a building with much in common with the Neues Museum, meant that this practice had an excellent track record of dealing with important early 19th-century neo-classical architecture.

NEW FACILITIES

The starting point for the design was the requirement for additional floor space for the exhibits, and the need for circulation problems across the site to be resolved. All the museums were linked together with colonnades which were open to the elements. These worked well on hot summer days, but to ensure the visitor numbers were maintained in the winter, DCA proposed to link the museums underground through the basements. A new entrance building was proposed to the west of the Neues Museum to relieve space requirements in the museums themselves, and to form the new access way to the subterranean network.

In the Neues Museum DCA’s idea was to glaze over the two courtyards to provide additional space, and to reinstate the interior spaces of the original galleries. The question was how to treat these spaces. Clearly as much as possible of the surviving fabric had to be conserved and retained, including all the fragments of historic fabric which had been rescued after the bombing. The problem was deciding how to design the new surfaces required to piece together the original fabric and all the rescued material. While the idea of recreating the missing fabric as a pastiche was anathema to the British team, the new material had to be sympathetic to the old. Not only was visual integrity necessary if the beauty of the original architecture was to be enjoyed, but visual integrity was also important from the perspective of the museum’s contents. An interior dotted with fragments of original architecture would distract from the displays of art and artefacts. A balance between restoration and preservation had to be struck, and some fierce arguments ensued.

CONSERVATION, RESTORATION AND PRESERVATION

The term ‘conservation’ when applied to the historic fabric of buildings and artefacts has a fairly broad meaning, encompassing every action which has the aim of ensuring the survival of the object. Under this heading falls a variety of different approaches which are often hotly debated. On the one hand there is the argument for restoring historic fabric so that the beauty and historic interest of the architectural composition can be readily appreciated and enjoyed by everyone. On the other there is the counter argument that this approach falsifies the history of the building.

|

|||

| A simple, modern glass roof was constructed over the Grecian courtyard, protecting the restored Schievelbein frieze and providing additional exhibition space below. The gallery in the foreground retains its pock-marked finishes. (Photo: Dennis Gilbert) |

Those historic buildings which were faithfully restored to their original condition in the post war years often now have the air of modern buildings constructed in the style of older ones. Since it is now difficult to determine what is old and what is modern, the approach devalues the original. Furthermore, if modern materials are also used, such as cement-rich renders, the modern reconstructions will never age in the same way. Visually at least, this approach can obliterate all sense of history.

Schinkel himself is quoted by Julian Harrap as saying that ‘Restoration should only extend to defects that pose a threat or are likely to do so in the future, and these defects should be rendered safe as inconspicuously as possible’.

More recently The Venice Charter,

which sets out internationally recognised

guidelines for the conservation and

restoration of monuments and sites, states

that:

‘Replacements of missing parts must

integrate harmoniously with the whole, but

at the same time must be distinguishable

from the original so that restoration does

not falsify the artistic or historic evidence’.

(Article 12 of The Venice Charter, 1964.)

Taken out of context, this approach could be taken to rule out the restoration of any damaged element. The charter does not go that far by any means, since it actively promotes restoration work which aims ‘to preserve and reveal the aesthetic and historic value of the monument’ provided that it stops ‘at the point where conjecture begins’ (from Article 10 of The Venice Charter, 1964). Nevertheless, the wording illustrates a fundamental dichotomy which arises whenever the repair and restoration of historic fabric is concerned: How can an addition or restoration be both ‘distinguishable from the original’ and ‘integrate harmoniously’ with it? Or, to put this another way, how can an alteration or addition which ‘integrates harmoniously with the whole’ not ‘falsify the artistic or historic evidence’ to some degree?

THE NEUES SOLUTION

In addition to the design and conservation firms DCA and Julian Harrap Architects, the team responsible for deciding the future of the museum principally included the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (State Museums in Berlin), representatives of the Landesdenkmalamt Berlin (the LDA is Germany’s conservation authority), and the Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung (the government’s purchasing agency). Various NGOs and conservation bodies were also represented, such as Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz (the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation).

|

|||

| In this section of floor the original decoration has been consolidated and supplemented with a simple framework to delineate its architecture, giving context to the smaller fragments of the original. (Photo: Dennis Gilbert) | |||

|

|||

| The Nordkuppelsaal dome after restoration of the structure and conservation of its surviving plasterwork: the outlines of lost panels have been recreated on the lime-washed brickwork, bottom right, so that the eye can complete the architectural form of the original design without interruption. (Photo: Dennis Gilbert) |

The principles to be agreed by the team had to take into account the practical needs of a museum open to visitors, and the historical requirements of a landmark building which had been almost destroyed in the war.

Julian Harrap believes that in the aftermath of any war the desire to rebuild what has been lost is inevitable, and difficult to resist. And with such an important national building, right at the heart of the country, all options were going to be contentious. Nevertheless, the team resolved to restore only those elements which had survived, and all new work was to be clearly distinguishable from the old. While complete replacements such as the main staircase and new elements such as the roofs over the courtyard could be clearly modern, the juxtaposition of old and new in an element which had been patched and repaired called for moderation. A set of principles was devised to guide the individual teams of conservators and restorers entrusted with the different areas of the building.

As far as the restoration of surviving fabric and the reinstatement of missing fabric was concerned, the most obvious impact of practical requirements was in the distinct approaches taken to surfaces in regular contact with museum visitors, such as floors and doors, and those which did not have to bear the brunt of wear and tear, such as wall areas and ceilings.

Since only a third of the floor surfaces had survived in a state that could be repaired and conserved, one option was to retain the fabric in its existing condition and cover them over, either with a protective carcass of timber and carpet, or with glass plate so that the original surfaces could still be seen, albeit in a very different context. The other option was to repair and conserve the surviving surfaces and infill with new material, restoring the whole floor to a hard smooth, functional finish. It was this option that was selected, reusing fragments of the original floor as aggregate where conservation was not possible. The result is that around a third of the floor surfaces are original, while the remainder comprises a largely new floor which does not try to emulate the original floor design.Being made of the original material it clearly respects it in colour and composition. The new areas tie in well with the new staircase, which was designed as an entirely new element in a bold, crisply modern style, following the original design in outline only, as in this case the original staircase had been completely destroyed.

The surfaces above the floor could be treated with much greater freedom than the floors because they did not have to withstand the footfall of millions of visitors. They could be preserved as found, provided that their structural integrity was reinstated. Or they could be restored to their original condition.

This moderated approach to preservation is well illustrated by the restoration of the Nordkuppelsaal dome on the south side of the building, the top of which had been altered in the late 19th century and then destroyed in 1945. Exposed to the weather, the fabric below had become waterlogged, and much of the plasterwork had long since fallen off, or been removed during the structural investigations in the 1970s, leaving little of the original surface. In all, 14 grotesques and 12 genius paintings had been saved, catalogued and stored by the museum’s curators ready for eventual restoration. Nevertheless, there would still be significant areas of bare structure, and some parts would have been dotted with isolated fragments of the original decoration. The finished result of a puristic preservation approach could not have conveyed any of the character of the original structure. Its historic value would remain in an archaeological sense, but the vast majority of visitors would not have been able to appreciate it.

|

|||

| The Schievelbein frieze in the Grecian courtyard. The gallery in the foreground retains its original finishes unrestored. (Photo: Dennis Gilbert) | |||

|

|||

| The architects’ preferred solution for this gallery was to add a soft green wash to the restored surfaces to soften the impact of the surviving green. (Photo: Dennis Gilbert) |

The solution adopted in the dome was to complete its late 19th century structural form by rebuilding those elements that were missing using reclaimed brick. This reduced the amount of light coming through the opening above. With less glare the details of the surfaces could be seen more clearly. The areas of bare brickwork were simply treated with a lime slurry to tone-in with the plasterwork, picking up the outline of the ribs to help the eye across the lacunae, restoring to the dome its original order and form. The elements salvaged in the 70s were fixed back into their original locations. Damaged sections of plasterwork were consolidated, and missing sections were reinstated to make good the forms of the surviving coffered panels. However, these new sections of plasterwork were not painted, so they remain visibly distinct from the original areas. The result is a successful balance between a full restoration and preservation as found. The original fabric is clearly identified but without damaging the legibility of the architectural composition.

Elsewhere, elements of plaster and decoration retain shrapnel and weathering damage from the past, and almost everywhere the history of the building is clearly displayed. By focussing on restoring a cohesive framework, and by softening the impact of the areas of infill, the recent history does not detract from the enjoyment of what has survived. Indeed, the building has acquired a new life and visual identity which is unique and exciting. It is not a ruin, but some of the romance of a ruin has been captured by the approach.

When the museum briefly reopened in March 2009 without its exhibits, the newly transformed building received a rapturous welcome. Michael Kimmeman, writing in The New York Times described the result as ‘a modern building that inhabits the ghost of an old one … Even the 19th-century frescoes by Wilhelm von Kaulbach, which once traced the progress of man from the Tower of Babel to the glory of Prussia, persist as small fragments embedded high up in the brick, like half-recalled dreams come to life’.

The Neues Museum officially reopened on 16 October 2009.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- Conservation Principles, Policies and Guidance, English Heritage, London, 2008

- The Neues Museum: Conserving, Restoring and Rebuilding within the World Heritage, Seemann Herschel, Leipzig, 2009