Rock of Ages

The story of British granite

Ewan Hyslop and Graham Lott

|

|

||

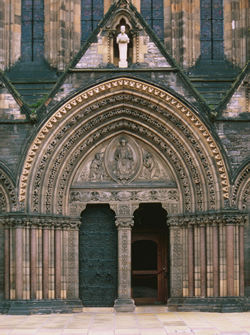

| Above left: the new Scottish Parliament, Edinburgh, completed in 2004, clad mostly using variable sized panels of pale coloured granite from Kemnay quarry in Aberdeenshire. Above right: main entrance to St Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh (built 1874-1917), constructed mostly from sandstone with polished Shap granite used for the columns. (All images: BGS©NERC) | |||

Probably every town and city in the United Kingdom has examples of buildings or monuments made from British granite. As one of the most distinctive of building stones, granite has long been prized for its strength and durability as well as its attractive appearance. Few stone types have been used for such a wide range of purposes, from structural and engineering foundations to decorative building interiors. As a material seen to represent prestige and solidity it was particularly favoured in Victorian times for commercial buildings such as banks, offices and entranceways to major ecclesiastical and public buildings. Granite was quarried in all corners of the British Isles, initially from coastal locations and transported by sea to the major urban centres. The UK was once a major producer of granite, particularly in the 19th century, and it was exported abroad to Europe, America and Australasia. The large variety of textures and colours present in British granite reflects the range of geological ages and compositional variation of granite throughout the United Kingdom.

The granite quarrying industry in Britain developed from the late 18th century. The principal areas of production were Aberdeenshire, Kirkcudbrightshire (southwest Scotland), Devon and Cornwall, Ross of Mull and Shap in Cumbria. Many other smaller scale quarries operated in other areas, generally supplying more local or regional needs.

THE ORIGIN OF GRANITE

|

|

||

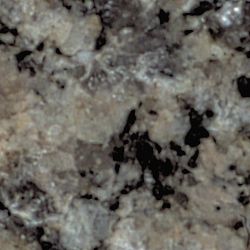

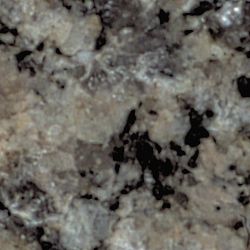

| Left: Typical Cornish granite from Trenoweth quarry, showing pale colour and uniform texture with dark speckles from biotite mica. Natural surface. Image approx 12cm high. BGS©NERC. Right: Granite from Trevone quarry, Cornwall showing typical pale grey colour and common large white feldspar crystals. Natural surface. Image approx 12cm high. | |||

In the British Isles, intrusions of granite and related igneous rocks are present in a variety of localities, and range widely in geological age and origin. Differences in mineral composition and conditions of emplacement mean that British granites show a wide range of colours and textures.

Granite forms from the cooling of large magma bodies at depth in the crust, the slow cooling allowing the growth of large and interlocking mineral crystals. Compositionally, granites typically contain 55-75% silica and are commonly pale coloured with medium to coarse grained crystals discernable to the naked eye. The interlocking crystals provide cohesion which adds strength and makes them suitable for polishing without plucking of the grains. Finer grained granites were typically used for structural purposes (e.g. foundations, walling, kerbstones, setts and paving), while coarser grained and porphyritic (i.e. with large crystals usually of feldspar) varieties were valued for ornamental work. The predominance of silica and other relatively stable minerals in granite make it particularly strong and durable.

|

|

||

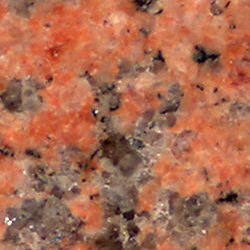

| Left: Granite from Retallack quarry in Cornwall, showing typical pale colour with large elongate white feldspar crystals, once termed 'horses teeth' by quarrymen. Natural surface; Image approx 12cm high. BGS©NERC. Right: Shap granite from Cumbria, one of the most distinctive of British granites with its large flesh-coloured feldspar crystals. It was widely used and favoured for decorative use. Natural surface. | |||

GRANITE IN SOUTHWEST ENGLAND

The principal granite quarries in England were in Devon and Cornwall, with several quarries in each of the five separate intrusive granite masses which form a chain across the Devon and Cornwall peninsula. Production was in its heyday in the 19th century, centred on the Dartmoor (Haytor quarry), Bodmin (Cheesewring and De Lank quarries), St Austell (Luxullian quarry), Penryn (Carnsew & Penryn quarries) and Penzance areas. Most have a light grey colour and are typically coarse-grained and porphyritic with both grey and pink feldspar varieties. Granite has been used for buildings and monuments in Devon and Cornwall from prehistoric times. Significant quarrying began in the 18th century, an early example being the use of De Lank granite from Bodmin, Cornwall for the Eddystone Lighthouse in 1756 and the Beachy Head Lighthouse in 1828. In London, Dartmoor granite was used for Waterloo Bridge in 1817, and for the construction of London Bridge in 1831 (Princetown granite) and again for its widening in 1902. A light grey medium grained biotite granite from Merrivale, Devonshire was used for the retaining river embankments for the Houses of Parliament in 1840.

The introduction of steam ships stimulated the Cornish granite industry from about 1840, with large quantities used to build docks throughout southern England, and from this time these granites were used extensively in London for numerous monuments, buildings and many of the 19th century commercial dock schemes and bridges. Examples include Nelson's Column (Foggintor granite) and Tower Bridge (Cheeswring granite), construction of the Thames Embankment (1865 to 1885) and the Thames bridges at Putney, Kew, Vauxhall, Blackfriars, Tower Bridge and Blackwall Tunnel.

|

|

|

| Truro Cathedral, constructed 1880-1910 from Carnsew granite from Cornwall. | Tower Bridge, London, completed in 1894, using Cheesewring granite from Cornwall. |

OTHER ENGLISH GRANITES

Shap, Cumbria. Despite the relatively small size of the granite intrusion at Shap it has had major commercial success as a decorative building stone. Its coarse porphyritic nature with conspicuous pink tabular feldspar crystals makes it one of the most readily identifiable granites. It has been widely used for monumental work throughout the UK and polished columns of pink Shap granite can be seen in most UK cities (e.g. entrance pillars to St Mary's Cathedral, Edinburgh). Shap granite was particularly favoured in London as a polished decorative stone and examples can be seen in the entrance to St Pancras Station, parts of St Paul's Cathedral, and the Prince Albert Memorial.

Mountsorrel, Leicestershire. A variable suite of igneous rocks in Charnwood and adjacent areas, termed 'granites' by the stone trade, have been exploited as building stones mostly for local use. In south Charnwood, coarse-grained, purple and green mottled diorites have been quarried at Groby and Markfield and are readily identified in buildings in and around the district. In north Charnwood the pink to grey Mountsorrel granodiorite was used for kerbstones and setts which were exported to cities and towns across the country from the early 19th century. As a hard and intractable stone, it was also commonly used as large irregular rubble stone blocks in the walls and houses of older buildings in villages near the quarries. In the 19th century, numerous local churches and houses were constructed or 'restored' using large blocks of dark red Mountsorrel granodiorite. Stone is still quarried at Mountsorrel, although it is mostly crushed for aggregate.

GRANITE IN SCOTLAND

Scotland has a relatively large number of granite intrusions, ranging widely in composition and geological age, with stone from the different regions having different characteristics, for example the silver grey granites of Galloway, the deep reds of Ross of Mull and Peterhead, and the salmon pink of Corrennie in Aberdeenshire. The city of Aberdeen, known as 'the granite city' is built extensively of silver-grey granite from quarries within and around the city. Many quarries have been used to provide a local building material, but in several areas they were exploited on a larger scale for export.

|

|

||

| Left: Ross of Mull granite from the West Highlands of Scotland. Polished surface. Image approx 12cm high. BGS©NERC. Right: Peterhead granite from Aberdeenshire. Polished surface. Image approx 12cm high. | |||

Aberdeenshire

granite. The Aberdeen granite industry developed from the

18th century, with stone first sent to London for paving in 1764

and the construction of Portsmouth docks a few decades later.

Through the 19th century the industry expanded and the area became

a world-renowned producer of granite. The industry was of huge

importance to the local economy, and materials and skills were

so plentiful that much of the city of Aberdeen was constructed

from granite. A relatively sophisticated transportation system

(canal and railways) allowed material from quarries further inland

to be transported to the coast, and the stone was exported in

great quantities to the main urban centres. There were

many granite quarries in Aberdeenshire, producing stone of varying

colour and texture,

and exploited for a wide variety of uses.

A number of the major quarries are described below.

Rubislaw quarry in Aberdeen reached over 90 metres deep, and was known as 'the deepest hole in Europe'. It opened in 1741 and, along with several other quarries in and around the city, produced a grey muscovite-biotite granite extensively used for building in Aberdeen and also widely exported (e.g. Bell Rock Lighthouse in 1806, Waterloo Bridge in London 1817 with other granites).

Peterhead, one of the most important Aberdeenshire granites, was produced as two varieties, known as Red and Blue Peterhead, both exported throughout the UK and abroad during the 19th century. The red variety was better known and used for ornamental construction and monumental work e.g. London, Cambridge (St John's College Chapel pillars) and Liverpool (St George's Hall pillars). Blue Peterhead was used for decorative building and ornamental work, e.g. the base of fountains in Trafalgar Square and the Prince Albert Mausoleum.Peterhead granite is still quarried at Stirlinghill and Longhaven quarries, where it is mostly crushed for aggregate.

Kemnay quarry began production in the mid-19th century producing building stone, setts and kerbs, with the best material reserved for polished monumental work. It is a light grey muscovite-biotite granite. Examples include the Queen Victoria Memorial in London, the Forth Railway Bridge and, more recently, as cladding for the new Scottish Parliament.

Corrennie is a medium grained biotite granite with a salmon-red colour making it favoured for decorative use. Examples include the Glasgow City Chambers and the Tay Railway Bridge. The light grey speckled muscovite-biotite granite from Dancing Cairns quarry has been used in Trafalgar Square, the Thames Embankment and part of London Bridge. Fine-grained dark greyish-blue biotite granite from Dyce quarry was favoured for the interior of London banks and exported overseas to Australia (Bank of Australia, Melbourne). Both Kemnay and Corrennie quarries are still active, along with a number of other granite quarries in Aberdeenshire, but their granites are mostly crushed for aggregate and roadstone, although dimension stone can still be obtained.

|

|

||

| Left: Granite from Corrennie quarry in Aberdeenshire showing distinctive salmon-pink colour. Polished surface. Image approx 12cm high. BGS©NERC. Right: Criffel Granite from Dalbeattie quarry in southwest Scotland showing typical grey colour with pink feldspar crystals. Polished surface. Image approx 12cm high. | |||

Galloway granites. The granitic rocks of the Criffel intrusive mass of southwest Scotland were extensively worked in a number of quarries at Creetown and Dalbeattie. The stone is typically grey (known as 'silver-grey') with pinkish feldspar. From the 1820s large quantities of stone were transported by sea for major dock and bridge works, for example at Liverpool and Swansea. Later it was worked for dimension stone, setts, kerbs and monumental use. At one time, the polished Dalbeattie stone was favoured in London for ground floors to buildings. The granite was extensively used for buildings throughout the local district around the quarries, and is seen today in villages and towns throughout the area. The Dalbeattie quarries today produce mostly crushed rock aggregate.

Scottish Highlands (Ross of Mull). A number of granite quarries operated throughout the Scottish Highlands, most supplying local stone, with a few larger scale quarries mostly producing setts and kerbstones transported by sea southwards to the main urban centres. By far the most important of these was Tormore quarry (Ross of Mull granite), which gained a substantial reputation and was used throughout the UK and beyond. The stone is an attractive coarse-grained reddish-brown colour and was used as decorative columns and ornamental stone for the construction of Glasgow University (1865), and in London, Manchester, Liverpool and as far away as New Zealand. It was said to have produced the largest granite blocks in the UK at over 16 metres long, with 5 metre blocks shipped to the US. Its northern coastal location made it suitable for lighthouse construction (e.g. Skerryvore, Ardnamurchan, Dhu Hartach and Hyskeir lighthouses) and its structural qualities were utilised for the Blackfriars, Westminster, and Holburn Viaduct bridges in London, and the Jamaica and Kirklee bridges in Glasgow. The quarry was reopened for a time in the 1990s and still has reserves of stone.

|

|

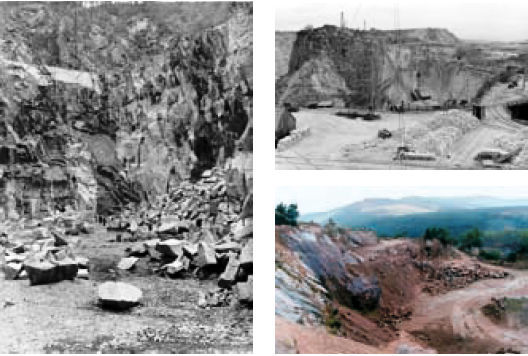

| Left: Rubislaw granite quarry, Aberdeen in 1939 showing stone blocks brought down by a recent blast. The quarry opened in 1741 and reached over 90 metres deep, and was described as the 'deepest hole in Europe'. BGS©NERC. Top right: Kemnay granite quarry in Aberdeenshire in 1939, showing setts and kerbstones stockpiled next to a railway which crosses a bridge over an access road. A 'Blondin' lifting cable is also seen. BGS©NERC. Bottom right: Corrennie quarry in Aberdeenshire. The quarry has recently been worked for crushed rock aggregate, but retains stockpiles of large block for use as dimension stone. |

WALES

Granitic rocks in north Wales have long been exploited for building and decorative purposes. The principal sources of granite are the outcrops at Trefor and at Nanhoron on the Lleyn peninsular in Gwynedd. The Trefor granite is fine to medium grey granite (microgranodiorite), principally used for local walling stone, but also provides a hard stone used in the production of curling stones. Nanhoron granite is also fine grained, grey-brown in colour, and mainly used as a decorative stone. Stone from the Llanbedrog quarries in Caernarvonshire have been used for structural and engineering use, in particular the building of docks. Setts for paving were produced from the Graig Llwyd quarry near Penmaenmawr in North Wales.

CHANNEL ISLANDS

Hornblende

granite from Guernsey, noted for being hard and fine-grained,

was transported to London from the 1820s for roadmaking and

paving, and used for construction of the

Thames Embankment in

the second half of the 19th century. Jersey supplied a coarser

grained pink tinted granite, with stone from the La Moie quarries

near St Helier used for the construction of Chatham Docks.

IRELAND

There are a number of granite intrusions throughout Ireland, with early quarrying taking place at the Dalkey quarries near Dublin from 1680. Some granite was exported to London for paving, and grey Wexford granite from Carnsore Point and Killiney Hill was used for construction of parts of the Thames Embankment. Pinkish grey Newry granite (Castlewellan and Glenville quarries) was used for structural work throughout Ireland, and selected for the base and pedestal of the Albert Memorial (1864-76), and provided setts for Belfast. Stone from the Ballyknockan quarries in Wicklow were used for the construction of Trinity College Dublin in 1832 and the museums in 1889. In Galway, the Shantallow and Barna quarries produced a pink to grey granite for building and monumental use, and provided setts for Dublin.

THE FUTURE FOR BRITISH GRANITE

|

|

| Traditional building constructed using random granite rubble from Mountsorrel quarry, Leicestershire. |

Today, almost all production of granite dimension stone in the UK has ceased, although many of the original quarries are still open, largely producing crushed rock aggregate, roadstone and other bulk products. There are 52 quarries currently working granitic rocks, some of which provide dimension stone for specific projects, and several quarries retain stockpiles of large block specifically for this purpose. In recent years there has been a resurgence in the use of granite, particularly for decorative interiors and cladding. However, most of the granite used now in the UK is imported from overseas.

The enduring quality of British granite is evident from

the numerous buildings, structures and monuments throughout the

country built from granites showing a rich variety of colours

and textures. Many of these are now well over a century old. That they

have not diminished with time testifies to the quality of the

material and its role as a world-class

building material.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- JGC Anderson, The Granites of Scotland, Special reports on the mineral resources of Great Britain, 32, HMSO, Edinburgh, 1939

- British Geological Survey, Building Stone Resources Map of the United Kingdom, British Geological Survey, Nottingham, 2001

- W Diack, 'Rise and progress of the granite industry of Aberdeen', The Quarry Managers' Journal, April 1941-February 1942

- JV Elsden and JA Howe, The Stones of London: A Descriptive Guide to the Principal Stones Used in London, Colliery Guardian Co Ltd, London, 1923

- GF Harris, Granites and Our Granite Industries, Crosby Lockwood & Son, London, 1888

- EK Hyslop et al, Stone in Scotland, UNESCO/International Association of Engineering Geology, 2006

- GK Lott, 'The Development of the Victorian Stone Industry', in England's Heritage in Stone, P Doyle et al (eds), English Stone Forum, Folkestone, 2008

- GS MacLeod and RWD Fenn, 'The Dalbeattie Granite Industry', Tarmac Papers: The Archives and History Initiative of Tarmac plc, 3:219-261, London, 1999

- J Watson, British and Foreign Building Stones: A Descriptive Catalogue of the Specimens in the Sedgwick Museum, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1911

- AA Warnes, Building Stones: Their properties, Decay and Preservation, Ernest Benn Limited, London, 1926