Victorian and Early 20th Century Tile Schemes

Lesley Durbin

|

|

| Detail of the Charing Cross Medieval Hunting Frieze, c1889 (by kind permission of the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust) | |

|

|

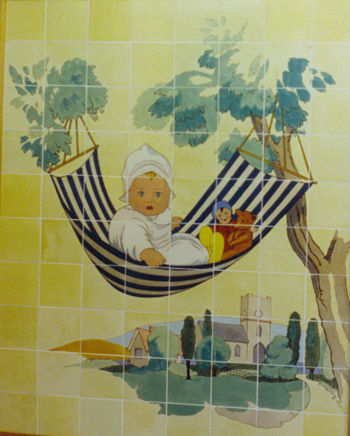

| Rock-a-bye Baby; one of the Ealing Hospital Panels by Carters of Poole, c1930 |

Tiles have been used as a medium for artistic and creative expression throughout the ages and the finest examples, such as murals and the work of William de Morgan at the end of the 19th century, have, rightly, always been regarded as individual works of ceramic art. However, tiled surfaces are common in old and historic buildings and the tiles themselves are, by their nature, so numerous that they are often regarded as being merely utilitarian and disposable, particularly the most recent examples. Furthermore, because tiles have always been mass-produced, generally using cheap and readily available materials, the individual object is often under appreciated. The result, over the centuries, has been the loss of the greater mass of ceramic tile material representing successive ages of manufacture, often merely due to changes in fashion.

What therefore should be our guiding principle for conserving tiles today? Given the diversity of age, location and provenance found under the heading 'tile' it is not always helpful to fall back upon ethical conservation practices which dictate that all historical fabric is of equal importance and as a result must be preserved. Assessment of all facets of the tile or tile scheme in question must be prominent in our minds before any decisions leading to actions are made.

Age is of prime importance when we consider the practical options for the conservation of tiles dating from medieval times through to the end of the 18th century. We might almost say that any fragment of functional ceramic which has survived thus far deserves to be preserved whether it is aesthetically beautiful or not. Furthermore, we must consider whether particular tiles are too important or too fragile to remain in situ, when safe storage is available and desirable. Conversely, if the interpretation of the site is of primary importance, the integrity of the fabric may take precedence over its fragility, and there may be some justification for the tiles remaining in place, whatever the cost. If we use matching new material, must it be to enhance or extend the original only, or can it be used to replace the original if the original is best served by safe storage? Once the best interests of the tile fabric, in terms of location, are determined, what is certain is that it is our duty to retain and preserve all examples of pre-industrial age ceramic tile whether fragmented or whole. The importance of examining, assessing and recording the underlying mortar should also be a factor for consideration in almost all circumstances.

In terms of any sort of conservation or preservation, 19th century tiles were largely ignored until the late 1970s except for a few small collections of tiles, housed in museums with a particular connection to their provenance, which were classified as 'objects'. In particular, the Jackfield Tile Museum in Ironbridge, Shropshire, which was founded in 1983, is a museum of the history of tile manufacture covering the period between 1834 and 1960. In addition to conserving, restoring and displaying the very large collection of tiles and plaster patterns, the museum quickly became a focus for the conservation of tiles in the wider context of the built environment.

Initially the conservation emphasis was on rescuing and preserving large collections of decorative tile panels or ceramic art which were under immediate threat of destruction by demolition. Notable inclusions were ten pictorial hand-painted tile panels by WB Simpson from the Charing Cross Hospital, a further ten nursery rhyme panels by Carter's of Poole from Ealing Hospital and the ceramic mural by Gilbert Bayes, Pottery through the Ages from the Doulton House at Lambeth. In all three cases - and many since - when demolition and complete loss of decorative art panels has been threatened, ruthless, but effective methods employing large diamond cutting saws have been used to free the ceramics from their Portland cement settings. Such methods inevitably damage the tiles which subsequently require extensive restoration. Examples from each of these three buildings now enjoy permanent exhibition space at Jackfield Tile Museum, with the remainder on display at the new Charing Cross and Ealing hospitals and at the Victoria & Albert Museum respectively.

In the more enlightened time in which we now work, with the protection given to tiles by the listing of buildings, the emphasis is to allow important decorative pictorial panels to remain in place and to become positive elements of buildings which have been refurbished and put to new uses. Nevertheless, there are occasions when important pieces of tile art need to be moved. A recent example was a large tile mural, designed by Gordon Cullen, dating from the late 1950s and some 40 feet long, which was scheduled for re-siting due to re-development in Coventry city centre. In this case, a completely different approach was taken in order to significantly reduce the probability of damage to the ceramic. Rather than cutting and separating individual tiles from the cement substrate as in earlier examples of re-siting, the panel was cut into just eight large sections measuring approximately 2.0m x 1.5m each and moved, still adhered to some 350mm of pre-cast concrete substrate, using heavy lifting equipment. A great deal of careful preparation and precision work was required to cut, lift and re-seat each piece successfully, resulting in only minor damage to the ceramic fabric.

The emphasis during the above removal and re-siting projects, and many others like them, was on the time and effort expended to protect every individual tile from damage, and to retain all of the original tile material.

|

|

| Detail of Pottery through the Ages by Gilbert Bayes |

The same principles do not hold, however, as best practice for the restoration of many 19th and 20th century interior tile schemes in working buildings, where a more flexible attitude to repairs and alterations is required if the building is to remain in use. (A redundant building will rapidly deteriorate, losing all its historic fabric, not just its tiles.) Many historic interiors are now being restored to their former glory so that they can continue to function as working buildings well into the 21st century. Indeed, the original beauty and quality of schemes is often fully appreciated by the occupants of the building.

That said, we also require high standards of cleanliness, functionality and quality for the fabric of our public buildings and places of work. In an important interior, such as one of the principal spaces of a hotel, chipped, fractured, missing, worn and dirty tiles are considered unacceptable, no matter how grand and splendid the interior was in its heyday. In these situations the conservation approach is usually applied in its broadest sense, and preservation of the scheme as a whole entity takes priority over individual tiles in much the same way that decayed stone and brick is replaced on external elevations. If a scheme can be retained and admired in the future by replacing the most badly damaged of its individual components and retaining all the rest, then that course is generally considered acceptable.

Fundamental to this approach is the absolute requirement for any replacement material to match the original exactly in terms of colour and form: anything less will be considered by the client to be poor work, and may actually jeopardise the survival of the work in the long term. Care should be taken to record the repairs so that it will be possible to tell which tiles are new and which are original in the future. Care should also be taken to ensure that original material is not removed and replaced unnecessarily when either its condition is still acceptable or a minor repair will restore its condition back to the realms of acceptability. On site repairs to individual tiles can, and should be carried out if the damage is minor, such as holes caused by obsolete fixtures and fittings. Repairs should also be carried out on site if a particularly elaborate one-off moulding is deemed too complex or expensive to replicate.

Victorian geometric and encaustic tile floors are fairly common in entrance halls of domestic and commercial buildings, as well as in churches. Whether complex and beautiful in design or simple and elegant, they all share a common history of many years of dirt and footfall, affecting their surface to a greater or lesser degree. In order to preserve these tile schemes for the future in situ, trip hazards must be removed if accidents are to be avoided. It is best to replace the material worst affected by severe surface wear and fracturing in high traffic areas. For the most important schemes, it may be possible to repair damaged tiles using a filler material such as coloured polyester resin (which is reversible), but usually floor tiles which are badly damaged or irreversibly stained are replaced with matching new tiles.

|

|

| Detail of the art deco interior tile scheme in the D6 Building at Boots, Nottingham |

Although there is an onus on the owners of listed buildings to retain existing tile interiors within their refurbishment plans, quite often 19th century tile schemes simply do not fit with modern requirements for office layouts, disabled facilities, or public access for example. Doorways need to be let in, lifts installed and computer terminal networks established, particularly in hospitals, libraries or municipal buildings. Again the broad brush stroke of conservation is often applied by local authorities as guardians of their local heritage, and it has become increasingly acceptable, in all but our most important buildings, to retain what is the most effective part of the schemes, usually the ground floor, entrance halls and stairwells, while allowing upper floor or basement schemes to be used as sacrificial material for replacement tile.

The Exchange Building in Birmingham is an example of this type of approach. Originally built in 1896, this was one of the first two telephone exchanges in the country, and it is of enormous historic importance. Nevertheless, the building has been upgraded considerably since then to remain commercially viable, and many alterations have been allowed to its tiled decoration.

All interior tile schemes should be judged on their individual merit and it is especially important that an experienced tile conservator is consulted at the early stages of any redevelopment to survey the material and assess its overall condition and significance, as well as outlining all the options available for preserving the fabric to the best advantage.

It can be argued that in some circumstances, particularly art deco schemes of the 1930s, which often rely on a mass of undecorated tiling enhanced by small but significant architectural detail, that it is the design and style of the interior which is worth preserving rather the mass produced fabric of which it is built, and that as long as the exact balance, colour and detail of the scheme are preserved in total, then it is acceptable to replace worn out and damaged component parts and in so doing securing its long term future.

Maintaining a detailed record of all the alterations undertaken is a vital part of a conservation programme of this type. By contrast some schemes, such as the interior of Leighton House in South Kensington, are nationally important or have great artistic, historic or technological merit and must be preserved in their full originality. Whichever route towards preservation is taken, it should be our aim to maintain as many historic tile schemes in their original setting as possible.

Recommended Reading

- T Herbert and K Huggins, The Decorative Tile in Architecture and Interiors, Phaidon, London, 1995

- H Van Lemmen, Tiles in Architecture, Laurence King, London, 1993

There are also many other books on the history of tiles but very little on tile conservation. Buckland Books is a good place to look for titles in this field (email info@bucklandbooks.co.uk or tel 01903 717648).