T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

3

Foreword

I

F GOD IS IN THE DETAILS, as the cliché

goes, then this directory is the bible for those

seeking skilled practitioners who can preserve

the essence of historic buildings – an essence that

often consists as much in patina and the subtle

touch of a craftsman as in the raw materials. The

BCD is, in effect, a celebration of skill of the kind

that can easily be side-lined in a homogenised,

standardised and mechanised world.

Erosion of detail is one of our big problems. The

number of demolitions of historic buildings has

fallen, if not to negligible levels then certainly to

levels that are far lower than the post-war average.

In 1979 nearly 700 buildings were the subject of

demolition applications. That figure fell to just over

ten in 2013, a reduction of nearly 99 per cent and a

real vindication of the sustained efforts of building

conservation lobbyists over the past half-century.

So far, so good: on one level, the climate for historic

buildings is unprecedentedly benign. But behind

the figures lies a mass of smaller alterations, to

windows, doors, plan-form, fabric, setting. Assessing the impact of these now forms the bulk of the day-to-day casework of amenity

societies, for whom the staple is now not so much avoidance of catastrophic change as mitigation and amelioration of incremental

impacts. Cumulatively, over time, these can be almost as damaging.

The fact that we are in this position is hardly surprising. In part it is a product of success: if buildings themselves are being saved,

it is likely that more and more work will involve altering existing fabric. In an ideal world, it would also follow that the skills to do that

sensitively would be in greater demand and be placed at a premium. To some degree that has happened: the satisfying bulk of this

volume is testament to a thriving marketplace for building conservation skills.

But we can never be complacent. The will to save buildings is a necessary but not a sufficient condition of a healthy historic

environment. That also requires a willingness to seek and follow the right advice from people who know how historic buildings are

made, how they mature and how they decay: people, if you like, with an intuitive understanding of organic architecture. Quite often,

in the interests of a historic building, we suggest that applicants go back to the drawing board,

literally; or find a new architect; or commission a conservation appraisal; or seek specialist

skills. The last two of these, certainly, are about encouraging a deeper awareness of a living

building that is capable of speaking to those who understand the language. These days, when

house owners are routinely subject to anything from time pressures, to onerous building

regulations, to the blandishments of modern-day snake-oil salesmen peddling plastic windows,

it can be difficult, especially for the novice and even for those with good intentions, to follow

the path that is truly best for the building. In the midst of these confusions, time spent

browsing this directory is time well spent.

Lord Crathorne KCVO

President

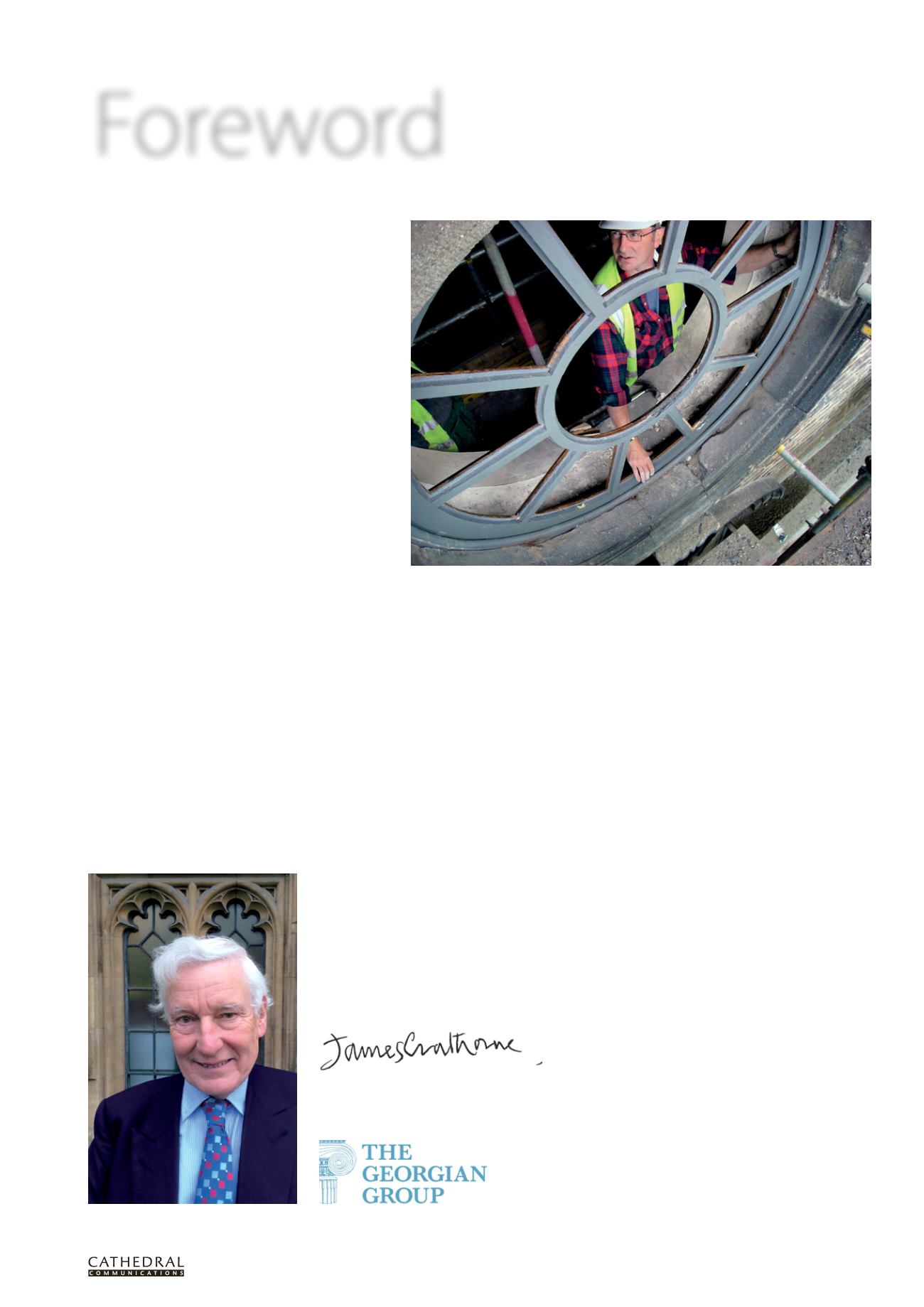

A restored radial window is returned to its rightful place during the conservation of a 1750s

townhouse in Newcastle upon Tyne. The project was commended in the Georgian Group/Savills

Architectural Awards for demonstrating light-touch conservation with an emphasis on retention of

patina and recovery of lost detail.