T W E N T Y T H I R D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 6

1 5 9

INTER IORS

5

COLOUR IN GEORGIAN

INTERIORS

EDWARD BULMER

T

HE START

of George I’s reign saw the

publication of two works which were to

have a powerful impact on architecture

and design in the Georgian period (1714–1830):

the first English edition of Palladio and the

initial volumes of

Vitruvius Britannicus

. Both

are now seen as manifestos for the adoption of

a classical approach to the design of buildings.

Important patrons began to adopt the ‘new’

classical style although, in truth, classical

architecture was not new to England – the

innovation lay in the rigour with which

classical design was now applied throughout

the building, and not solely to their exteriors.

This heralded the age of the ‘correct’ use

of the classical orders, in which line came

before ornament. Classical proportion could

now be adopted without the need for costly

decoration, so the highest status buildings

were sometimes the most august and the

simplest. It could be summed up as ‘grammar

not vocabulary’ – design for the mind as well

as the eye.

Fashion, while not being the only driver

(many existing buildings remained resolutely

un-remodelled) worked as it does today. What

the rich wanted they got and what the less

well-off saw the rich having, they imitated as

cheaply as possible.

Palladianism, as architectural historians

have now termed this classical revolution,

was a universal style. It had the great good

fortune of looking good in ‘common colours’

(see page 160) as well as the richest of

finishes. It was a style that had its roots in

stone building and, for walls, pilasters and

columns, the stony tones of earth pigments

included in the palette of ‘common colours’

were therefore very suitable. (Other common

colours included browns and greys which

tended to be used for distinct elements –

brown for timber elements such as window

joinery, but usually stone colours for skirtings,

whether or not made of timber.) Thus we

find that natural stone and stony colours

predominate even in high status interiors.

Although it should be noted that the

pigments used for this ‘cream through to

beige’ palette did differ in price (see Baty,

Further Information), the greatest difference

was made by the introduction of gilded

enrichments, carved furniture and deeply

dyed cloth for wall hangings and upholstery.

Much of this decoration was achieved with

imported materials and émigré craftsmen.

Contemporary conversation pieces and

portraits help us to visualise the effect of

these interiors.

Classicism embodied hierarchy, best

recognised in the orders, from Doric to

Composite. Ancient and, later, renaissance

writers sought to explain their meaning and

how to use them. By the early 18th century

architects and builders sought to employ

the orders as a narrative of their client’s and

their own learning, culture and status. They

were used to ornament interiors but also to

differentiate their function.

The entrance hall of a wealthy household

was a room to receive all comers, from

messengers to dignitaries and as such

was couched in terms of the exterior of

the building – finished in a sculptural

and emblematic idiom and furnished for

durability. A typical hall would not have

‘stuffs’ (no curtains or upholstery) as they

could harbour germs. Instead a polished

hall chair would proclaim the lineage of the

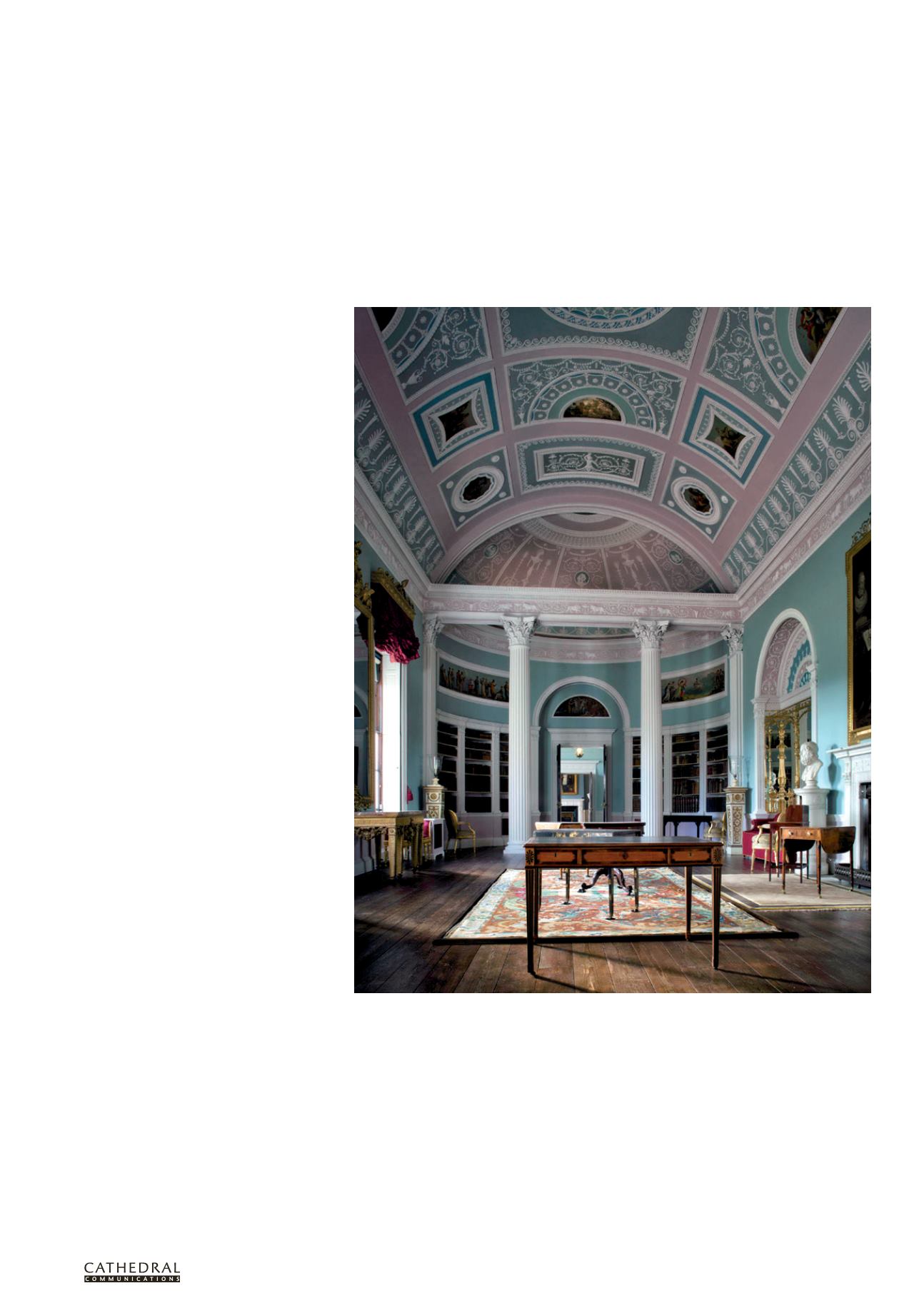

The Library at Kenwood after recent redecoration showing the colours used in the first decorative scheme.

The window cornices, one window seat and the pier glasses are the sole survivors of the original furnishing

that accompanied this scheme.