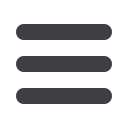

T W E N T Y T H I R D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 6

9 5

3.2

STRUCTURE & FABR I C :

MASONRY

JOINT FINISHES ON

HISTORIC BRICKWORK

GERARD LYNCH

T

HE FINISHING

treatments found on

the mortar joints of historic brickwork

reflect skills and traditions developed

over many centuries. Joints can account

for 15 to 30 per cent of the façade so when

skilfully executed they make an important

contribution to the overall aesthetics of

the finished brickwork. Understanding the

original appearance of brickwork is therefore

essential to its appropriate conservation.

Both the mortar and the joints’ surface

finish affect the brickwork in several ways.

The colour and tone of the mortar lightens or

darkens the overall brick facade. How joints

are profiled affects how light is caught and

reflected: recessing or angling the profile

creates shadows in sunlight, emphasising the

texture, whereas a subtle profile can obscure

the impact of the bricks allowing them to

merge into a homogenous surface.

Historically, when bricks were less

uniform in colour and regular in shape,

the joint finishes could be designed to add

accuracy and repose to premier facades by

creating the illusion of accuracy. This

trompe

l’oeil

effect relied on finishes to create a grid

on the centres of the beds (the horizontal

joints) and perpends (perpendicular joints),

using either fine grooves, pencilled (painted)

lines or precisely trimmed narrow ribbons of

fine mortar.

JOINTING

The finished profile of the original mortar

joint may be formed either immediately,

as the bricks are laid, or later in a separate

exercise known as pointing. Jointing is the

bricklayer’s term for the action of finishing

the joint faces of the bedding mortar as

work proceeds. It is the oldest method

for finishing brickwork and was mainly

executed using trowels until the early 17th

century when jointing tools increasingly

became standard. It continued to be used

for ordinary work and with the decline

in craft traditions after the first world

war, jointing predominated once again.

Advantages

• unified joint

• uniformity of joint in strength and colour,

provided mortar is accurately gauged

• reduced labour costs

Disadvantages

• less quality control of joint finish

(not all bricklayers joint well)

• difficulty in maintaining uniform

colour throughout the wall face.

POINTING

Pointing is the craft term used to define

the application of a separate and frequently

superior mortar onto the bedding matrix

which is then skilfully brought to the desired

finish. As lime mortars used in domestic

brickwork were slow-setting, the pointing

mortar was applied quite thinly to the still

soft bedding mortar, setting as a unified

compound joint. Pointing was reserved for

premier facades from the 17th century and

remained a common site practice until the

first world war.

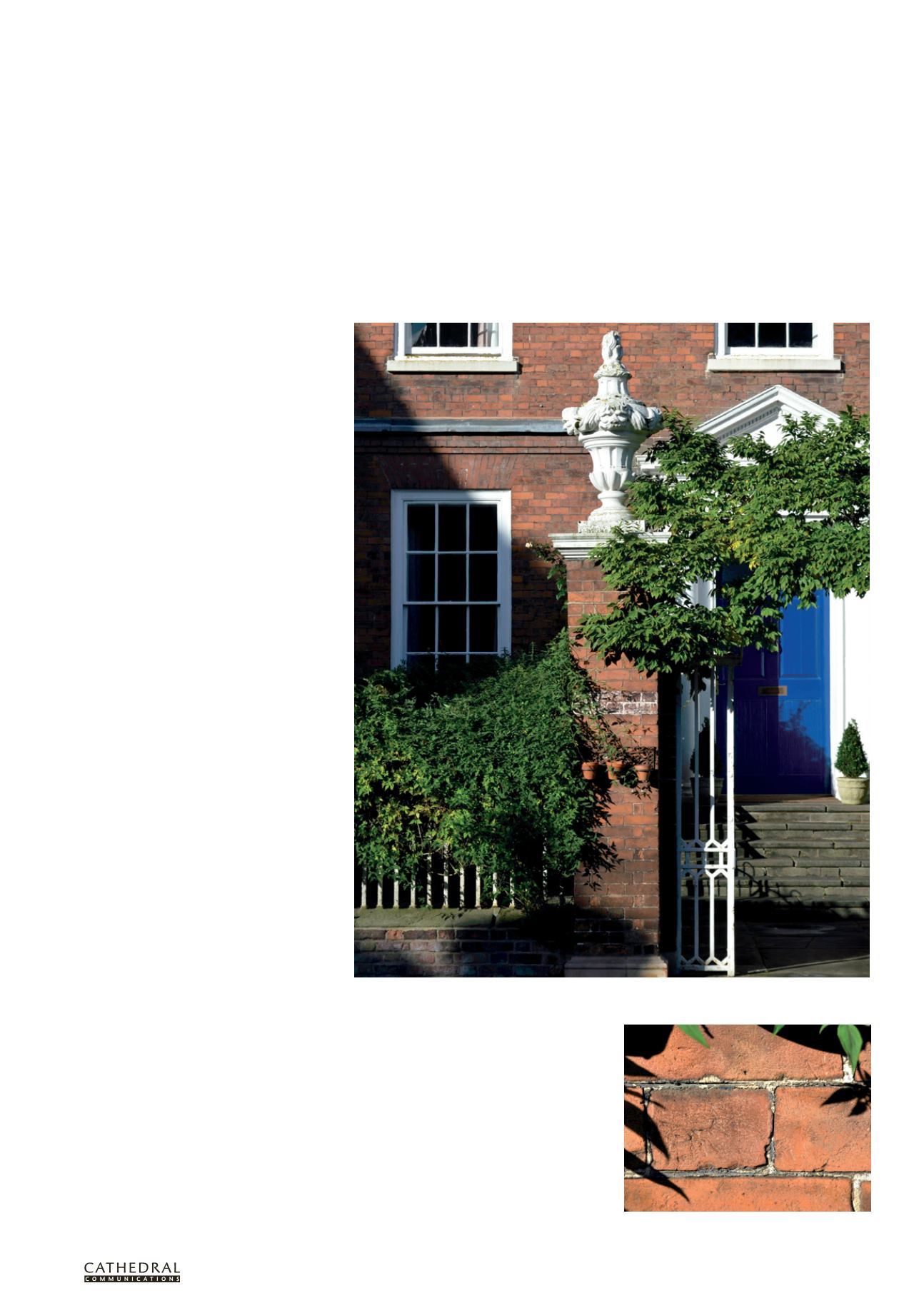

Evidence of the original ‘ruled’ joint finish on a gate pier in Miller’s Green, Gloucester c.1741