Basic HTML Version

26

Historic Gardens 2010

BCD Special Report

Malus pumila

and the pear

Pyrus communis

2

and they were competent in the skills of

grafting*, developing new varieties and

probably cider-making.

3

Perhaps surprisingly,

the 500 or so years of Roman occupation

left no written evidence or vestige in a

place name of such activities. The Angle,

Jute and Saxon invaders who followed the

Romans left a scattering of place-names,

such as Applegarth (‘apple orchard’) and

Appleton (‘where apples grow’), and these

are thought to refer to groupings of

Malus

pumila

established in the landscape.

1

Traditional orchard cultivation began

to decline with the fall of the Roman

Empire, but the associated skills and

knowledge may have survived into the late

medieval period within settled monastic

communities. Monasteries were well suited

to developing and cultivating skills such

as planting, grafting and pruning in their

monastic orchards or ‘pomaria’.

4

Henry

VIII’s Reformation destroyed many of

these orcharding centres, but his appointed

fruitier Richard Harris introduced grafting

material (scion wood) for pears from the

Netherlands and apples from France and

established orchards at Teynham in Kent.

During the 17th century much of our

fruit growing expertise centred around

aristocratic nurserymen such as Ralph Austen

and John Tradescant, and the writer John

Evelyn, who were influenced by continental,

and particularly French fruit-growing

heritage. These wealthy travelling plantsmen

collected fruit varieties and established

orchards in the estates and large houses of

England. Orchards became widely associated

with the aristocracy, as illustrated by the

number of National Trust properties that

incorporate historic orchards. Trees were

often grown in quite formal arrangements

on dwarfing rootstocks*, but larger trees

and spacious plantings more characteristic

of our idea of ‘traditional’ orchards occurred

as well. By 1700, orchards were a dominant

landscape feature in many counties.

The first written records of cider-

making date from the reign of King

John (1199–1216). By 1700 the counties

of Worcestershire, Herefordshire,

Gloucestershire and Somerset already had

a well-established tradition of orcharding

for the production of cider and perry. This

industry developed to use up surplus fruit

that could not be taken to market due to

the region’s then inadequate infrastructure.

5

These proliferating farm orchards would

often have been dual purpose: providing

fruit to eat, cook or store for the farm as

well as juice and alcohol. Cider became a

component of the farm labourer’s wage.

Many of the extant traditional orchards in

Britain are the legacy of the small-scale mixed

farming that was predominant before the

intensification of agriculture after the second

world war. As a result, these orchards are

often found close to settlements and usually

betray the location of former farms, now

shrouded in more recent development. This

proximity to habitation facilitated some of

the cultural associations that are still apparent

today, with orchards acting as centres for

‘songs, recipes, cider, festive gatherings... wisdom

gathered over generations about pruning and

grafting, aspect and slope, soil and season,

variety and use’

.

6

The wassail is one such

example of these ‘festive gatherings’ designed

to ward off evil spirits and encourage

productive cropping in the coming year. It

still occurs at Carhampton in Somerset, and

in many other parts of the West Country.

In contrast to cider orchards, perry pear

orchards with standard trees are a rarer

but more spectacular component of the

landscape of south-west England, with the

trees growing larger and older than apple

trees. Some of the old perry pear trees

that survive today date from 18th century

plantings, in keeping with the saying,

‘Walnuts and pears, you plant for your

heirs’. Luckwill and Pollard list 101 different

varieties of perry pear from Gloucestershire

alone, many being very localised.

The 19th century was a turbulent

period for traditional orchards, but by 1870

fruit growing was on the increase again to

provide for nascent markets (such as that

for jam) supplied by a new rail network.

From 1912 onwards, the standardised

rootstocks developed by the research stations

at East Malling, Merton and Long Ashton

enabled people to maximise their planting

arrangements for productivity, with the

vigorous type M25 rootstock the most

suitable for grazed traditional orchards.

Since 1950, fewer and fewer traditional

orchards have been planted and the national

stock of standard fruit trees is now heavily

biased towards an older generation of trees

that are more than 50 years old. The 1980s

saw the beginning of a significant push to try

to reduce the national dependence on food

imports with the advent of the Common

Agricultural Policy. Funding was made

available to convert traditional orchards

into more productive farmland causing the

widespread destruction of older orchards;

a pattern which, to some extent, continues

today. Over the last century virtually all fruit

grown for the consumer market has been

produced in intensive commercial orchards

that utilise semi-dwarfing rootstocks, a range

of chemical treatments and trees planted

closely in rows along herbicide treated strips.

Traditional standard orchards are still planted

in association with the cider industry, since

sheep-grazed orchards are a component of the

commercial set-up of a few producers, like

Julian Temperley at Burrow Hill, Somerset.

Biodiversity

The ecological value of traditional orchards

has long been underestimated and they

have only recently come to be appreciated

as biodiverse islands within a largely

intensive agricultural landscape. In 2004,

over 1,800 species were found across the

plant, fungi and animal kingdoms in just

2.2 ha of traditional orchard in the Wyre

Valley Site of Special Scientific Interest

(SSSI) in Worcestershire in the first study of

its kind in the UK.

7

In April 2009, Natural

England published a report on traditional

orchard biodiversity after surveying six

traditional orchards for diversity of species

and habitat features, with a particular focus

on bryophytes*, lichens, invertebrates and

fungi. Within these groups they found a

total of 810 species, and more generally the

sites were rich in nationally rare and scarce

species and contained a varied matrix of

different habitats including veteran fruit trees,

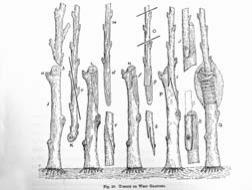

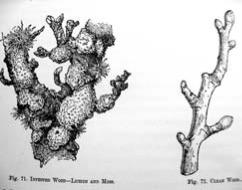

Two illustrations from John Wright’s The Fruit Grower’s Guide published in 1892, at a time when Victorian horticulturalists were devoting tremendous energy to the study of all aspects of fruit growing