Basic HTML Version

38

Historic Gardens 2010

BCD Special Report

However, cold baths were not only viewed

as a method of curing disease. Throughout

the century there was a renewed interest in

following a regimen to achieve good health.

According to Virginia Smith, ‘between 1700

and 1770 the medical advice book market

expanded intermittently but steadily’.

2

The

books often described modes of healthy

living that, the authors claimed, would extend

life expectancy. One of the many types of

routine advocated was the cold regimen,

which included spending time out of doors,

eating cooling foods, taking plenty of exercise

and bathing in cold water. One of the great

advocates of this regime was the philosopher

John Locke. In the 1703 edition of his tract,

Some Thoughts on Education

, he argued that:

Every one is now full of the miracles

done by cold baths on decay’d and weak

constitutions, for the recovery of health

and strength; and therefore they cannot

be impracticable or intolerable for the

improving and hardening the bodies of

those who are in better circumstances.

John Floyer, a Staffordshire doctor, was one

of the most high-profile medical men actively

promoting cold bathing during this period; his

pioneering work,

An Enquiry into the Right Use

and Abuses of the Hot, Cold and Temperate Baths

in England,

was published in 1697. Floyer’s

belief in cold water was not confined to the

written treatise, for in the 1690s he constructed

his own small bathing spa, St Chad’s Bath at

Unite’s Well, about a mile from Lichfield. The

restored remains of the spa are in the grounds

of Maple Hayes School, near Lichfield.

It is perhaps not surprising that cold

baths began to appear in several local gardens

soon after. One of the first was constructed

at Streethay Manor, north of Lichfield.

This is a fascinating moated site with strong

Floyer associations, as he was the relative and

friend of the family that owned the house,

the Pyotts. The remains of a late 17th- or

early-18th-century spring-fed, stone-cold

plunge bath-house (illustrated right) can

still be found in the grounds, no doubt built

with Floyer’s encouragement. It was placed

between the house and moat and is now

free-standing, but the stone foundations of a

wall running parallel to its south side have

recently been uncovered, suggesting that the

pyramidal-roofed structure might have been

the wellhead to a much larger cold bath room.

Cold bath houses and pools in

the landscape

Plunge pools and cold baths took several

different forms. The plunge pool at the

Georgian House in Bristol was built within

the actual villa in the 1790s by John Pinney,

a man who wanted his house filled with all

the latest modern conveniences. This reflects

a desire to explore new technologies and

possibly also later medical theories concerning

the need to regulate the temperature of the

water into which one plunged – something

which could be achieved more easily indoors.

Similarly, the late 18th-century plunge pool

at Greenway, Devon, was also fully enclosed,

although in this case the bath house was

situated away from the main house, on the

banks of the picturesque River Dart.

Plunge pools at Painswick in

Gloucestershire and Stourhead in Wiltshire,

on the other hand, are both external, each

differing in their placement. The 18th-century

plunge pool at Painswick (illustrated overleaf)

commanded open views across the landscape.

At Stourhead, in Wiltshire, the pool was

set within an ornamental grotto containing

statues and purposely sited to exploit a

designed view across the lake (top left).

In 1765 Joseph Spence described how the

jagged opening was ‘coverable with a sort of

Curtain, when you chuse it’, so that the inner

darkness could be transformed at the pull of

a drape, and plunge pool bathers could be

protected from the prying eyes of visitors on

the lake’.

3

In fact, the only way to get the view

through the grotto opening is to be at the

level of someone standing in the cold bath.

The remains of the late 17th or early 18th century bath house at Streethay, Staffordshire, which may well have been designed

with advice from cold bathing advocate, John Floyer (Photo: Timothy Mowl)

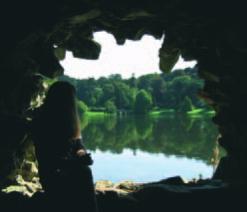

The view through the grotto and across the lake that Henry Hoare and his rollicking visitors

would have enjoyed in the plunge pool at Stourhead, Wiltshire (Photo: Timothy Mowl)

The statue of Neptune in the grotto at Stourhead