4

BCD Special Report on

Historic Churches

17th annual edition

of stained glass images in Cambridgeshire

and Sufolk, is another well documented

example of ofcially sanctioned action against

‘superstitious’ images. Other losses, such

as the medieval glazing of Worcester and

Peterborough Cathedral cloisters, were the

unfortunate result of an unruly soldiery.

It is easy to overemphasise the extent

of the losses incurred during this period.

When the city of York fell to parliamentary

forces in July 1644, the intervention of the

parliamentary commander, and Yorkshireman

Lord Tomas Fairfax, ensured that the

articles of surrender stipulated ‘that neither

churches nor other buildings be defaced’.

While a quantity of plate, three copes and the

monumental brasses were lost in the aftermath

of the surrender, the Minster’s medieval

windows remained largely unharmed. It has

been suggested that damage to the heads

of the fgures of archbishops in the 14th-

century Great West Window refect deliberate

iconoclasm, but the deterioration of the

medieval glass is just as likely an explanation.

Writing in the 1690s, antiquarian James

Torre was able to describe in considerable

detail stained glass in almost every Minster

window, although he described one window in

the north aisle as having been plain glazed as

a consequence of the glass being removed and

sold during ‘the late Troubles’. His reticence in

identifying the religious subjects depicted in

the windows may refect a continued anxiety

about the popish associations of the medium.

Despite Fairfax’s eforts, not all the

windows of the city churches escaped

unscathed, as in 1645 superstitious images

in the windows of St Martin’s Coney

Street were ordered to be ‘taken away or

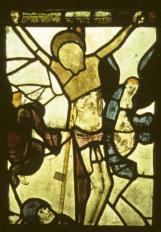

defaced’. Te damaged Trinity images in

the churches of St Martin (above) and Holy

Trinity, Goodramgate may well also refect

iconoclasm at this time, as parliament had

renewed injunctions intended to stamp out

images of the three persons of the Trinity.

Elsewhere, parishioners went to sometimes

extraordinary lengths to protect their windows

from loss. In the Gloucestershire parish

of Fairford, for example, the 28 windows

containing medieval glass survived the

Reformation, despite the Puritan zeal of Bishop

John Hooper, the second bishop of the newly

formed diocese of Gloucester. Te windows

enjoyed considerable celebrity and in the early

years of the 17th century attracted the attention

of two Oxford poets. Te arrival in nearby

Cirencester of parliamentary troops in the

summer of 1643 brought danger. In Cirencester

much damage was done, and in anticipation of

iconoclasm William Oldisworth, to whom the

Fairford rectory had been leased, took action

to safeguard the glass. Rather than remove

the windows wholesale, key details, especially

heads and upper part of fgures, including the

head of the Crucifed Christ in the east window

(below left), were removed for safekeeping,

in some cases never to return. In 1648, while

the Commonwealth still prevailed, the parish

commissioned local glaziers John and Edward

Scriven, to restore the windows, although in

1716 antiquarian Tomas Hearne reported

that some glass removed during the civil war

had still not been returned to the windows.

Hearne’s account also reveals that the

aged parish clerk, blind Richard Walklett,

conducted guided tours of the window,

reciting from memory the words of an old

‘Parchment roll’ that had since been stolen.

Walklett’s commentary shows that scenes

of pre-Reformation Catholic apocryphal

legend had been transformed into scenes of

impeccable protestant Bible history, preserved

for their didactic value. Te scene of Joachim

and Anna at the Golden Gate, for example,

had become ‘the salutation of Zacharias

& his wife Elizabeth’, while the birth of the

Virgin and her reception into the temple had

become ‘the birth of St John the Baptist and

the Virgin’s visit to her cousin Elizabeth’.

Te post-Reformation maintenance of York

Minster’s windows illustrates only too well

the impact of the Reformation on the craft of

stained glass. Te craft which had once been

so prominent in the life of the medieval city

had dwindled away and although the Minster’s

windows continued to be repaired, the task was

entrusted to plumber-glaziers such as Edward

Crofts, with apparently limited glass-painting

skills. When the nave windows were repaired

in the second half of the 18th century, the

Minster’s own glaziers undertook the glazing

repairs, while new painted glass was provided

by William Peckitt (1731–95), the self-taught

stained glass painter who was to become the

best-known exponent of the craft of his day.

Some of Peckitt’s earliest work for the

Minster was less than a success and his 1754

fgure of St Peter for the south transept failed

and was removed to be replaced with a new

and technically more profcient version in

1768. His provision of painted glass for the

restoration of the west window and the two

west windows in the nave aisles (1757–8)

cannot be judged to be entirely successful

either. However, he was careful to renew only

those parts of the heads that were missing,

and in the adaptation and reinstallation in the

Minster of the late 14th-century Jesse Tree in

c1765 Peckitt showed remarkable sensitivity to

the historic glass. In his later south transept

fgures of the 1790s (Abraham, Solomon and

Moses), the infuence of late medieval canopy

design at New College, Oxford, can clearly

be seen (facing page, small illustration).

It has been suggested that Peckitt may

have had a hand in the restoration of the

Minster’s Great East Window, the masterpiece

of Coventry glass painter John Tornton,

made between 1405 and 1408. Te complicated

Damaged 15th-century Trinity image, St Martin’s, Coney Street, York

An early 16th-century Crucifxion in the east window of

St Mary, Fairford, with head of Christ removed, prior to

restoration by Barley Studio (Photo: Barley Studio)