Basic HTML Version

BCD Special Report on

Historic Churches

18th annual edition

19

how to control bells more effectively.

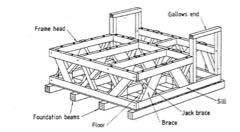

‘Change’ bell ringing (the ringing of

tuned bells in a pre-determined sequence)

developed during the 17th and 18th centuries

and spurred the modification and development

of stronger bell frames that could cope with

the forces generated by bells being swung

full-circle. Although there are many variations,

this group of timber frames, described as

‘long-headed’, form a box with top plates, sills,

foundation beams and braces to contain the

bells. Such frames were designed to hang the

bells in different alignments with lighter bells

counteracting the heavy ones. Full-circle ringing

meant that bells could be held motionless for a

second or two at the end of each full 360 degree

swing to allow the ringers to generate ‘changes’

by altering the sequence in which bells are rung.

There are a number of frame types.

These were first classified by bell historian

George Elphick in 1945 and more recently

updated by Christopher Pickford FSA.

Threats to timber bell frames

The greatest threats to the survival of this

resource of fine historic engineering and

craftsmanship are neglect, the re-hanging

of bells, and augmentation (increasing the

number of bells to an existing ring). Many

churches, particularly those in rural areas,

are at risk of redundancy. There are fewer

regular Sunday service bell ringers and even

fewer practice nights, when bells and their

frames and fittings are usually maintained.

Without maintenance, the timber bell frames

fall into disrepair, allowing decay to spread

and causing the bells to become unusable.

A broken louvre, leaking lead roof or

damaged downpipe can easily lead to the frame

becoming saturated. Ultimately, the timber

bell frame will rot with fungal decay or invite

Death watch beetle, which favours damp oak.

A structural failure in the tower will put a stop

to bell ringing, perhaps indefinitely. Inevitably,

the company of ringers will move to another

church or just give up their art leaving the bells

and historic timber frame to deteriorate.

The re-hanging of bells or augmentation

may mean altering an existing historic timber

bell frame or, at worst, replacing it with a steel

one. The desire to add further bells is driven by

an active and enthusiastic band of ringers who

want to develop their unique cultural heritage of

change ringing and preserve their craft. Often

in the past, little consideration has been given to

their significance and the impact that alteration

will have on the historic timber bell frame.

The process of change

Whereas alterations to secular listed buildings

require an application to the local authority

for consent, the principal denominations

in England, Scotland and Wales all operate

internal systems of control which exempt them

from this. Within the Church of England, for

example, no alterations, additions, removals

or repairs to a church, its fabric, ornaments

or furniture may be made without a ‘faculty’.

Where bells and their frames are concerned,

the DAC must be consulted, via their bell

advisors, as must the consultative bodies

including the CCCBR and English Heritage.

The following national amenity societies

would also be notified: the Society for the

Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), the

Church Buildings Council (CBC), the Ancient

Monuments Society and the Council for

British Archaeology. With later structures

this could involve the Georgian Group, the

Victorian Society or the Twentieth Century

Society. Once the consultative bodies have

been advised, it is the diocesan chancellor who,

through the diocesan consistory court, issues

the faculty to allow the work to commence.

Objections to inappropriate works are heard

through the diocesan consistory court,

presided over by the diocesan chancellor.

Applications should be submitted with

supporting documentation including plans

and, for most denominations, two ‘statements’:

the statement of significance and the

statement of need, before recommendations

for management and change are made.

In order to identify the significance of a

bell frame, it is necessary to understand and

evaluate its fabric, construction, age, whether

it is the work of a single maker and whether

the frame bears any important inscriptions.

For example, there is a fine example of a signed

and dated frame at the Church of St Botolph,

Slapton, Northamptonshire (title illustration):

a locally made frame for two bells installed

in 1634 by Thomas Cowper of Woodend.

It is important to know how and why

the frame has changed over time and the

relationship with its setting in the tower,

including ancillary elements such as

clock mechanisms or carillons. It is then

necessary to consider, in the words of

English Heritage’s

Conservation Principles

:

• who values the place, and why they do so

• how those values relate to its fabric

• their relative importance

• whether associated objects

contribute to them

• the contribution made by the

setting and context of the place

• how the place compares with

others sharing similar values.

Clearly, the last remaining early medieval

timber bell frame in Dorset is of exceptional

national historic significance, as are the

detached timber bell cages at East Bergholt,

Suffolk and Wrabness, Essex. But would

a medieval timber frame which has been

altered over the centuries with only a

fragment of medieval work remaining

have the same significance? The question

is impossible to answer generically – each

case must be judged individually.

Regional differences can also contribute

to the significance of a particular bell

frame. Historically, timber was relatively

rare in areas such as Cornwall, compared

to Herefordshire, East Anglia and South

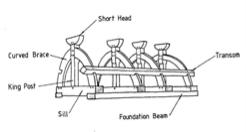

St Thomas a Becket, Hill Croome, Worcestershire:

A simple medieval king-posted frame with steep

braces with heavy transoms across the ends of the

three parallel pits. The transoms are stepped to allow

the bells to swing and give clearance for the clappers.

(Photo: Christopher Pickford)

St Mary, Pakenham, Suffolk: Timber oak plate

repaired with new scarf joint with compatible

material (Photo: Douglas Kent)

Medieval shorted-headed king post frame truss

Long-headed box frame, 18th–19th century (Diagrams: Christopher Pickford)