Basic HTML Version

22

BCD Special Report on

Historic Churches

18th annual edition

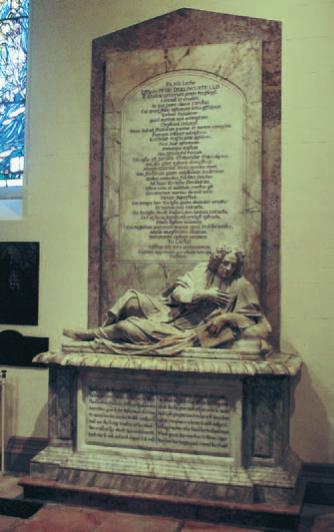

Baroque Drelincourt monument in the north aisle

perfect symmetry of form, slightly veiled

beneath its flowing folds. The features

are strongly expressive of intelligence,

mildness and benevolence, and were

peculiarly admired, by Dr. Drelincourt’s

contemporaries, for the strong

resemblance which they bore to the

original. The whole monument is, indeed,

an exquisite piece of workmanship,

perfected by the hand of Taste,

usque ad

unguem

.� On the front of the sarcophagus

[is an] appropriate inscription.⁴

Behind the figure of Drelincourt is a tall slab

of marble on which is carved a fulsome Latin

inscription giving an account of Drelincourt’s

history and background and mentioning the

Ormond connection, among much else.

The Stuart monument

This is now in the north aisle, and is a

distinguished work of Francis Leggatt Chantrey

(1781–1841). Born in Jordanthorpe, Norton,

near Sheffield,

5

young Chantrey had only a

rudimentary education, but around 1808 he

determined to concentrate on sculpture and

moved permanently to London. He soon

achieved fame, and King George III sat for him

in 1809: this royal patronage marked the start

of an illustrious and prolific professional life.

In 1809 too, he married his cousin, Mary Anne

Wale, who brought a substantial dowry to the

marriage, and his career took off at a spectacular

pace. Chantrey’s standing led King William IV to

confer a knighthood on him in 1835, and when

he died the sculptor left a considerable fortune.

His splendid monument in Armagh,

a serene masterpiece of Neo-Classicism,

commemorates William Stuart (1755–1822),

fifth son of John Stuart (3rd Earl of Bute and

prime minister from 1761 to 1763) and his

wife, Mary Wortley Montagu (only daughter

of Edward Wortley Montagu and Lady Mary

Wortley Montagu, the celebrated letter-writer,

who introduced inoculation against smallpox

to Britain in 1721). William Stuart was ordained

in 1779, and 1793 saw his appointment as

Bishop of St David’s. His homilies were greatly

admired by King George III, and in July 1800

he received a request from the King to consider

assumption to the office of Primate of Ireland

and was duly translated to the See of Armagh.

As archbishop, Stuart was indiscreetly critical

of his fellow-bishops, largely because of their

failure to promote education. He chaired the

Irish Board of Education Inquiry and under

his ægis that organisation issued 14 influential

reports between 1809 and 1813. He also

oversaw a poorly conceived ‘restoration’ and

re-ordering of the cathedral, which had to be

comprehensively unpicked and remedied some

25 years later. Stuart had an unfortunate and

premature death owing to a mix-up between a

bottle of embrocation and one of laudanum.

As far as is known, Chantrey carved three

memorials that were erected in Ireland. Apart

from that to Archbishop Stuart, he produced

the funerary monuments of John James

Maxwell (2nd Earl of Farnham) in Urney Parish

Church, Cavan (1826), and of Major-General

Sir Denis Pack in Kilkenny Cathedral (1828).

Stuart’s monument was ordered in 1824 and

completed in 1826: it cost a thousand guineas,

then a very considerable sum. In addition,

there was the expense of transporting it to

Armagh, where it was originally erected in June

1827. Rennison recorded that ‘Mr Chantrey’s

Man’ had arrived to do the work,

6

and that a

place for the monument had been ‘fixed on’.

7

The place selected was in the south aisle,

so the figure of the archbishop originally faced

west. Chantrey’s completed work attracted

some criticism: the ‘stiffness of the arm or rather

shoulder which adjoins the wall’ was noted,

for example.

8

William Makepeace Thackeray,

however, visited Armagh in 1842 when

collecting material for his Irish Sketch Book and

singled out the ‘beautiful’ Stuart monument

for praise, finding the cathedral as a whole ‘as

neat and trim as a lady’s drawing-room’.

9

Primate Stuart had presided over some very

curious alterations in 1802, including the placing

of an altar at the west end of the nave,

10

but by

the late 1830s such travesties of ecclesiastical

arrangements were seen as unacceptable.

However, the Cathedral Board Vestry Meetings

also reveal that there was some re-ordering

and shifting of positions of monuments in the

1880s.

11

In 1886

12

Alexander James Beresford

Beresford Hope (1820–87, politician, author,

ecclesiologist, and architectural pundit) wrote

a letter recommending the appointment of the

architect Richard Herbert Carpenter (1841–93,

son of the early Gothic Revivalist Richard

Cromwell Carpenter [1812–55])

13

to carry out

new works of restoration and re-ordering.

Carpenter was at that time in partnership with

Benjamin Ingelow (d1925), and Beresford Hope