Basic HTML Version

40

BCD Special Report on

Historic Churches

18th annual edition

Cuthberti virtutibus, proved that the saint’s

power endured. A late 12th-century manuscript

that was probably Reginald’s own autograph

copy is kept in the cathedral treasury. When

Cuthbert was disinterred 11 years after his death

he was found ‘whole, lying like a man sleeping,

being found safe & uncorrupted & lyeth awake,

and all his masse clothes safe & fresh as they

were at ye first hour that they were put on him’.

2

In 875 he was again disinterred when

the monks fled before Viking incursions.

The community entrusted with the care of

these sacred relics was defined by that task

and their ‘Exodus’ experience which lasted

120 years until, while trying to return with

the body to Chester-le-Street where they had

sheltered before, the bier on which the saint

was borne became fixed to the spot. After

fasting and prayer to determine what this

meant, the bishop and the community had

a revelation that the body should be carried

to Dunholm, a hill (or ‘dun’) on an island (or

‘holm’; ‘Dunholm’ gradually evolved into the

modern ‘Durham’). His last resting place was

miraculously revealed to them and a temporary

shelter of wattle was built. Then ‘the Bishop

came with ye corpse and with all his [strength]

did worship’.

3

The cult was now permanently

located on a protected and virgin site, divinely

revealed. The bishop then began work on:

a mykle [little] kirk of stone, and

while it was in [the] making from

ye Wanded kirk or chapel they

brought ye body of that holy man

Saint Cuthbert: & translated him

into another White Kirk so called,

& there his body Remained [ four]

years, while ye more kirk was builded,

then the Bishop Aldun did hallow

ye more kirk or great kirk so called

before ye kallends of September, &

translated Saint Cuthbert’s body out

of ye white kirk into ye great kirk as

soon as ye great kirk was hallowed

to more worship than before.⁴

It seems improbable that Cuthbert’s body was

moved from the wattle church (which even then

appears to have had a stone tomb for the saint)

into a ‘White church’ (implying stone) for four

years before being translated into the greater

stone church at its consecration on 4 September

998.

5

Different interpretations are compatible

with the text of the manuscripts.

6

Whatever the

finer details of that sequence, however, there is

no doubt that the sanctity of the relics and the

established liturgy of the cult of St Cuthbert

dictated the fundamental characteristics of

the architecture from its precise location to its

size and material. Only the most important of

buildings at this date were of stone, so if there

was an intervening smaller church of stone,

then this was a sequence of utmost significance.

In the new abbey church, completed

in 1020,

7

Cuthbert’s shrine was on a broad

pavement elevated ‘[three] yards high, being

in a most Sumptuous & goodly shrine above

ye high altar called ye fereture’.

8

This raised

pavement recalled the first feretory in St Peter’s

Church on Holy Island. Bishop Cosin’s Roll

manuscript continues, describing the saint’s

tomb in the cloister,

9

‘when he was translated

out of the White Church to be laid in the

Abbey Church’, resulting in multiple sites for

veneration. Cosin goes on to describe a carved

and painted stone effigy of the saint, with

mitre and crozier ‘as he was accustomed to

say mass’, placed above the tomb which was

enclosed by a wooden screen. This created

a miniature church, recalling the first one of

wattle which had received Cuthbert’s body

on his miraculous arrival. That resting-place

had been sanctified and memorialised at what

was either another temporary resting-place

for Cuthbert’s reliquary or had possibly been

Cuthbert’s shrine in the Saxon Cathedral.

10

The structure, in any event, remained

in the garth (a garden enclosed by a cloister)

until the Dissolution, near the door where

deceased monks were carried for burial in

the garth. The monks thus made a journey

similar to Cuthbert’s, passing the same

sanctified place, in the hope of the same final

destination in heaven. In this monument, the

long Exodus and the miraculous designation

of its end is called to mind in order to bring

out the full significance of the saint’s tomb.

Processions to the monument and to the

tomb or high altar were, then, redolent of

the memory of that extraordinary Exodus

experience. The high altar was just to the west

of the intended final tomb, so the mass, which

joined the worship of the community with

the worship of heaven, was reinforced by the

relics which were the existential connection

with the saint who continued to intercede

on their behalf in the courts of heaven.

The monumental structure in the cloister

stood until the Dissolution when Dean Horne

caused it to be demolished and its material given

over to his own use. He had Cuthbert’s effigy

set against the cloister wall. Dean Whittingham

had it defaced and broken up to remove all trace

of the cult of saints. Whittingham believed in

the sanctity of the Word, not of places, spaces

or things, and this major theological shift in

the notion of sanctity would cause a similar

shift in the patterns of use and focus of the

architecture. The radical nature of this shift can

hardly be exaggerated; Cuthbert’s presence had

defined the community from before his death

‘The North Prospect of the Cathedral Church of St Mary & St Cuthbert at Durham’, J Harris, 1727 (Cathedral

Library, Durham)

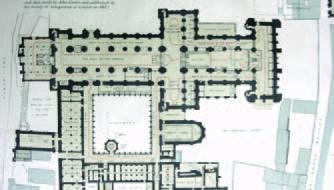

Plan showing the ancient arrangements according to existing remains and other evidence [Based on the

Ordnance Survey 1/500 Plan (1860), and that made by John Carter and published by the Society of Antiquaries

of London in 1801]’, WH St John-Hope, in Fowler’s edition of Rites of Durham