BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

21ST ANNUAL EDITION

21

worn, although there were also areas where

porosity in the original casting had allowed

material from the core to leach through to

the surface. In several places there were large

encrustations of salts and corrosion products

forming a distinct disfiguring layer, with

further corrosion continuing underneath.

There were also problems where the

separately cast components of the piece

had been joined. In places, the sections

had been brazed in with copper, which

was an entirely different colour, and there

were areas where pieces of metal appeared

to have been hammered in to fill gaps.

Water entering the sculpture through the

original casting joints and through corrosion

holes presented a problem for the room

beneath, where the book of remembrance

is displayed. The book was removed to be

digitally recorded, conserved and temporarily

displayed at the University of Manchester.

In addition to working on the repair and re-

instatement of the page-turning mechanism,

conservators at the university also had to

consider adding new pages to commemorate

those killed in more recent conflicts.

CLEANING

The removal of the book of remembrance

in early May 2013 allowed Eura’s staff to

begin the process of testing appropriate

cleaning techniques. It was decided to

select a small area of horizontal surface not

visible from the ground and closely examine

the lacquer to determine its condition

before carrying out cleaning trials on it.

A lightweight scaffolding tower was used

to gain access to the base of the bronze and

an area on the south west corner was chosen

for the trials. Micro-photos were taken of

the selected area before and after testing to

enable precise recording and assessment of

each treatment. The area was then cleaned

using a one per cent solution of Triton

X-100 non-ionic detergent, agitating with

natural bristle brushes. The surface was

swab-dried, rinsed with de-ionised water

and allowed to dry. To the naked eye there

was no apparent difference between the

trial area and the surrounding metalwork,

although it could be seen from the swabs

that some soiling had been removed.

It was clear from the micro-photographs

that the lacquer was thicker in some places

than others, that the colour varied considerably

and that green corrosion products were visible

in many places. Examination of the surface

also showed that the sculpture was greener

where the lacquer was more severely degraded.

Once the trials had been completed the

results were disseminated to all interested

parties, including WMT and English Heritage,

to allow for discussion of the best way forward.

As the lacquer coating was clearly failing

it was necessary to remove it, a conclusion

supported by English Heritage’s consultant.

Further trials were carried out and

the best results were obtained with a

dichloromethane-based solvent. The use of

dichloromethane has been heavily restricted

under EU REACH (Registration, Evaluation,

Authorisation and restriction of Chemicals)

regulations since 2012. However, its use

is sometimes necessary when removing

historic treatments which weren’t applied

with reversibility in mind and, if used

carefully by conservators, it can safely remove

coatings without damaging the substrate.

The memorial was completely scaffolded

and screened for access and safety reasons.

Further protection was added by laying a

geotextile membrane (a permeable synthetic

fabric) over surfaces to collect residues and

to protect the local drains from the run-

off of cleaning products and old lacquer.

The dichloromethane was applied with

soft bristle brushes and swabbed off, and the

bronze was thoroughly cleaned between coats

with a high pressure steam cleaner, taking

care not to damage any existing patina. Even

with this treatment it took up to five coats in

some areas to fully remove lacquer residues

from sheltered crevices. All chemical residues

were caught in the geotextile membrane

and removed from site for safe disposal.

The removal of the lacquer coating

allowed for further assessment of the

surface and a photographic reference

was made of problem areas.

While some loose corrosion products

were effectively removed by repeated steam/

pressure washing, there were still areas of

active corrosion, intractably stubborn salts

and black sulphide accretions to deal with.

Working closely with WMT and the other

organisations concerned, it was agreed that

the worst areas of active corrosion should

be selectively and carefully cleaned further

using the wet Jos method. Jos is essentially

an air/water abrasive cleaning system which

is suitable for removing active corrosion

from bronze. In this case the medium used

was marble dust (calcium carbonate) mixed

with water and applied under pressure.

On bronze statuary, great care must

always be taken by the operatives when using

an abrasive system like Jos as it is possible

to damage the surface of the bronze. For

this reason, only a select group of well-

experienced operatives and technicians

was allowed to undertake the process. In

addition, it was used as lightly as possible

and only in those areas where it was

absolutely necessary, with a small nozzle

fitted to confine the spread of the medium.

Nevertheless, at the end of this process

there still remained, in places, very thick

coatings of salts or black sulphide deposits

despite water/steam pressure of up to 80

bar and selective Jos treatment. So, the final

stage in the process was the careful removal

of these deposits by hand, using wooden

spatulas, bronze spatulas and dental picks.

The whole sculpture was again

fully washed and steamed before

patination trials were commenced.

SURFACE REPAIRS AND PATINATION

Large holes and cracks in the surface of

the sculpture were repaired with bronze

mesh solidified with bronze-loaded resin.

Smaller areas were filled with bronze-

loaded resin or, wherever possible, with

coloured microcrystalline wax.

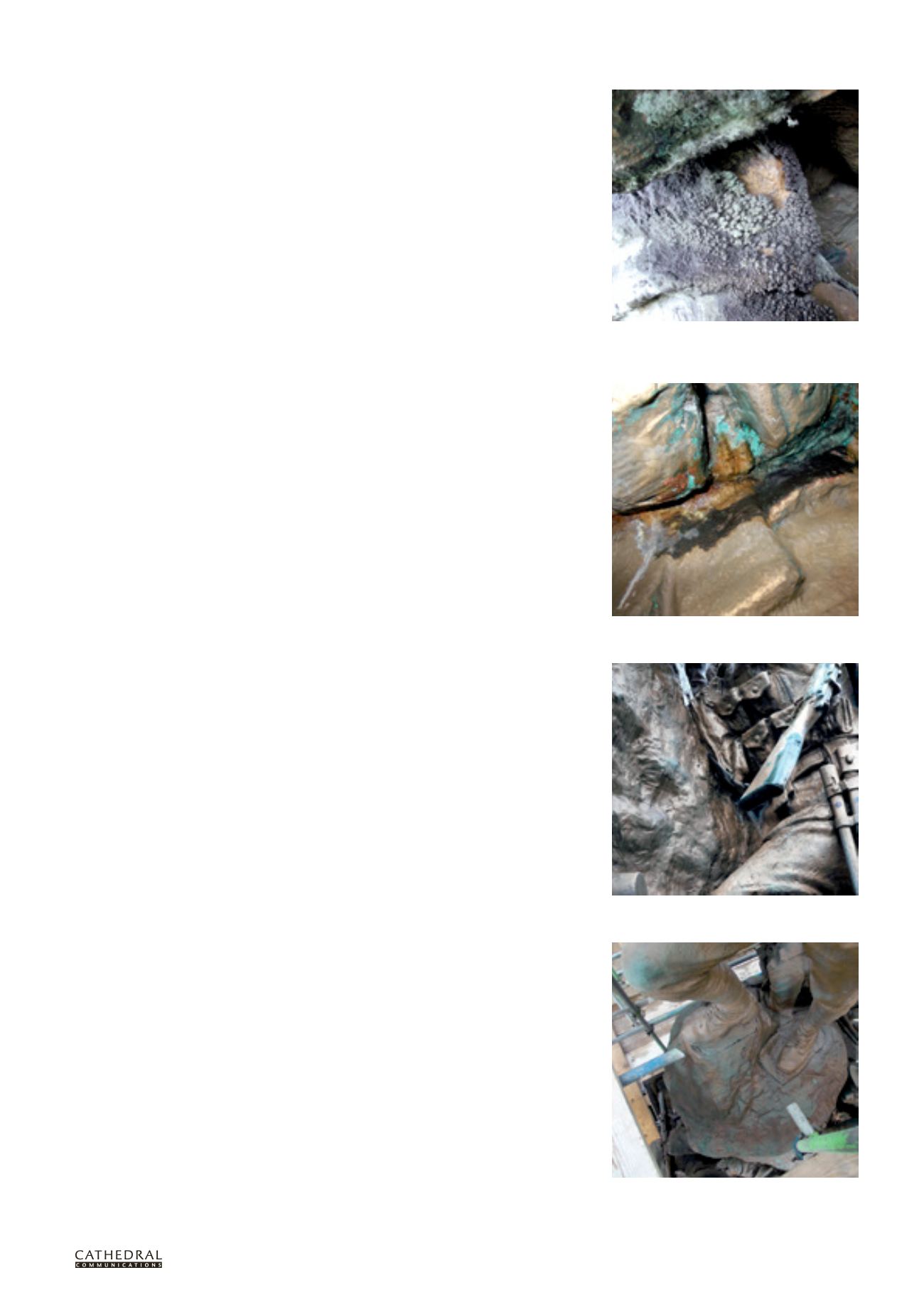

Salts and other material which had leached from

the core of the bronze formed thick encrustations in

some areas.

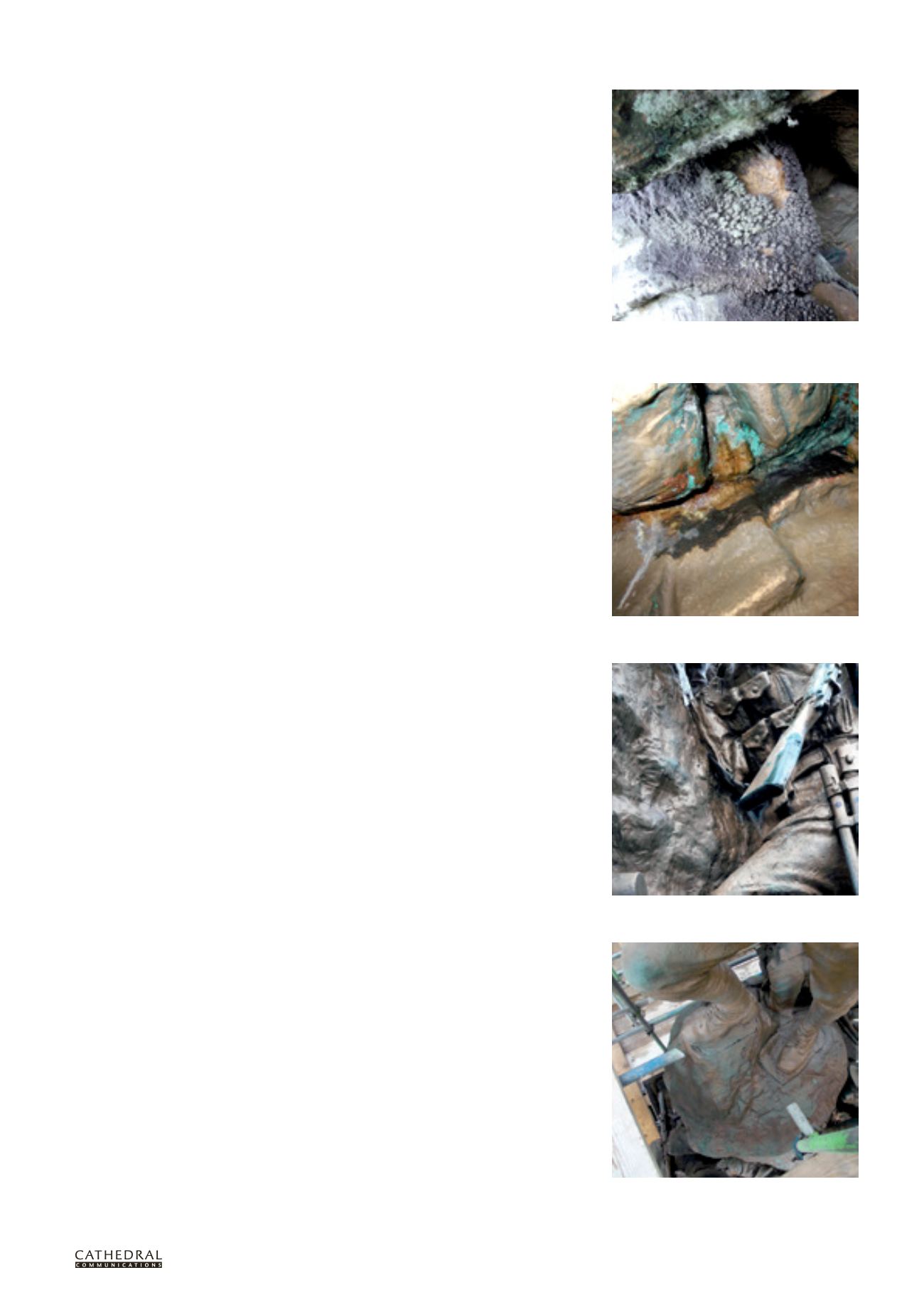

Salt accretions with active corrosion (the green areas)

and a band of black sulphide staining

Poorly sealed gaps at the feet of the topmost soldier

where the castings had been joined together

Staining and pitting around a large, active corrosion

hole which had penetrated to the core of the rifle butt