Reviving the Cross Bath

Peter Carey

|

|

| The Cross Bath seen from Bath Street, and (bottom right) the same elevation in 1987 |

The Cross Bath, a small, unique and beautiful gem of a Georgian building, sits somewhat precariously over its own spring source in the heart of the World Heritage city of Bath, the latest in a succession of structures stretching back for at least 2,000 years. Despite extensive alteration over the centuries, it is a Grade I listed building in its original use, previously with scheduled monument status and recently designated a national sacred site by the World Wildlife Fund. The story of its revival encapsulates much of the history of the spa as a whole.

BACKGROUND

On 7 August 2006, three years to the day after the Three Tenors concert which should have celebrated the opening, the magical waters of Bath were once more made available to its citizens and the wider public. It had been nearly 30 years since all bathing was stopped following the death of a young student who had contracted meningitis after a routine swim. The cause of death was eventually proved to be an amoebic infection from Naegleria fowleri, a well-known yet potentially deadly inhabitant of most hot-water springs around the world.

|

In the days before the Millennium Commission and its £7.5 million match-funding grant, which finally convinced the city to take on the project itself, the intervening period was one of raised and dashed hopes as one private scheme after another proved unworkable.

Since its re-opening, the spa has exceeded all predictions for visits and popularity among a worldwide public, although the cost has left many local council taxpayers far from happy. The problems of the construction phase are still under debate but should not obscure the importance of the scheme's longer-term, real achievements. These include:

- The restoration of an essential facility to a city whose very name it evokes

- The rejuvenation of an abandoned key area of a World Heritage city

- A critical element in the long-term functioning and attractiveness of Bath as a tourist destination, helping to revitalise the local economy

- The spearheading of a resurgence in a spa culture within Britain

- The provision of a contemporary iconic building by the renowned architect Sir Nicholas Grimshaw

- The renovation of a number of unique historic buildings

- An important example of creative co-operation between the local authority as client and development controller, English Heritage, the local amenity bodies, the Millennium Commission as catalyst, and a European private-sector spa operator.

LOCATION

|

|

| The Melfort Cross of 1739 by John Fayram | |

|

|

| Elevations from Baldwin's 1783 scheme | |

The Cross Bath stands at the western end of Bath Street, the 18th-century colonnaded masterpiece by Thomas Baldwin which links the only three natural hot spring sites in the country. King's Spring, which lies at the east end of the street, feeds the Roman Baths and the famous and elegant Georgian Pump Rooms. The remaining two, the Cross Bath Spring and Hetling Spring, which feed the Cross and Hot Baths respectively, are both within the new spa site.

The Millennium project incorporates three other listed buildings: the two Grade I listed properties, 7/7a and 8 Bath Street, which form the south-western crescent end of Baldwin's grand development, and the Grade II listed Hetling Pump Room opposite the Hot Bath, where in Georgian times the waters of the Hetling Spring could be taken.

Nicholas Grimshaw's new building, re-titled the New Royal Baths, now occupies the site of the only non-listed building in the complex. This was a 20th-century adaptation of Decimus Burton's Tepid Baths, then built as a medium-temperature municipal swimming pool.

These four buildings form the spa complex which is operated under the new name of Thermae Bath Spa by the Dutch-owned Thermae Development Company (UK).

INFRASTRUCTURE

By 1987 the whole of the western end of Bath Street was in a dreadful state. The buildings had been abandoned for ten years and a swimming facility directly to the north had been burned out. All the surrounding buildings were still suffering from the coating of black carbonation and coal smoke that had been the previous hallmark of Bath. The area was uninviting and unvisited. The city council was desperate to encourage regeneration, but equally determined not to be drawn into running a spa operation for which it had no expertise.

The council's initial scheme was aimed at encouraging private-developer investment. It included removing the fountain from in front of the King and Queen's Bath to open the views down Bath Street, and repaving with cobble setts to improve the appearance and to encourage slower-moving traffic and favour pedestrians. Donald Insall Associates was commissioned to clean, repair and consolidate the two major Georgian baths: the Cross Bath and Hot Bath.

At the same time, elimination of the contamination from the spring supplies was undertaken by a combination of bore holes and tube wells. These tap the spring sources at a much lower level where the oxygen content of the water is too low and the temperature too high for the amoebic pathogen responsible for the student's death to survive.

Concurrently, planning permission was given to develop the site of the burnt-out New Royal Baths as a new commercial shopping mini-mall called the Colonnades, all intended to encourage people back into the area.

PHASE I REPAIRS 1987-93

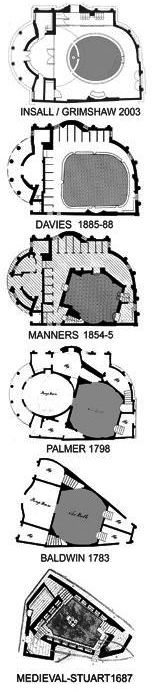

In the 1890s, Major Davies, the then city architect, had undertaken major consolidation works at the Cross Bath. The original internal pool walls had been removed from the south and east, the pool itself had been remodelled in concrete in a semi-kidney shape, and a heavy concrete, vaulted structure had been constructed below the Georgian walls.

|

These underground chambers were drained for the tube well installation. This also gave the archaeologists a brief window to investigate and record the Roman remains. However, de-watering these spaces caused a very worrying shift in the foundations, so the chambers were rapidly re-flooded and the drilling rig adapted to bore sideways and create a number of ground anchors. This meant that when Phase II was being conceived, no possible alteration to Major Davies' concrete groundworks could be entertained.

Before conservation could commence, the masonry had to be gently cleaned using nebulous spray washing. Removal of the carbonation and soot deposits soon revealed the extent of stonework damage and decay, and repairs were scheduled with the number of replacement blocks kept to a minimum, while not being shy to expose the scars of time and patina of age where not of structural concern. The cleaning and conservation works were carried out by Gregory Thain Ltd and the decorative stone consolidation and repair were undertaken by Roland Stone Masonry Ltd and Nimbus Conservation.

The plaque of King Bladud, which was part of the 18th-century Baldwin design, was brought back to the site, conserved and placed behind the great chimney feature which overlooks the pool. The remaining fragment of the Baldwin 1783 pool wall was also carefully conserved and consolidated at this time using pure lime mortars and shelter coats. The fine Corinthian capitals to the colonnade and blind screen were cleaned using poultices, and conservation repairs were undertaken, all of them having been encapsulated during the primary washing and cleaning phase.

The 20th-century flat roof to the Hot Bath was heaving with dry and wet rot, having enclosed a steamy atmosphere for many years. There were similar concerns for the timber structures surrounding the Cross Bath pool. Changing cubicles of 20th-century origin were taken down to reveal the condition of the primary masonry structures behind.

Research had shown that the building had been entirely roofed over in the early 20th century, resulting in the decorative panels either side of the chimney being removed to provide ventilation, and the urns taken down to accommodate the roof structure. But, although the brief for the first phase excluded improvement works, sufficient evidential basis survived for a careful replication and recarving of those details. This was undertaken by Simon Verity.

Overall, this initial phase was very successful. The work won the Europa Nostra Conservation Award in 1993 but, ultimately, it failed over the next few years to produce a satisfactory and viable proposal from any private developer.

PHASE II, THE MILLENNIUM PROJECT

Paul Simons, past SPAB Lethaby Scholar, joined the council as Economic Tourism and Development Officer and quickly spotted the opportunity that the Millennium Commission could offer of a matching grant towards a council-led redevelopment of the site. However, it was made clear at the outset that this was not to be a Heritage Lottery grant and that the criterion was for a contemporary facility to be provided. This laid the ground for the selection of Sir Nicholas Grimshaw and Partners to lead the project and to design the new building element of the development.

Given the practice’s previous experience of the site, Donald Insall Associates was chosen as architect responsible for the repair and alterations to the other six listed buildings on the site, with Arup for structure, water and services engineering, and Speirs and Major Associates for lighting design.

Undoubtedly, the greatest challenge for the conservation team was the re-interpretation of the jewel-like Cross Bath. As often happens, the prior historical research, while sufficient for the repair phase, had drawn a blank just where it mattered most: the plan form of Thomas Baldwin’s 1783 pool and pump room remained unclear, and it was not known what alterations were made by John Palmer, ten years later. Mid 19th-century plans, made after the pool had been extended and the pump room and changing rooms amalgamated, were all that was available. However, careful inspection of an unexplained section of ashlar wall led to the first eureka moment when a barely detectable curve in its form was revealed, raising the possibility of an oval pump room. This form resolved the skewed axis of Baldwin’s pool with the perpendicular axes of Palmer’s rebuilding. (These latter axes relate to the then new Bath Street alignment.) Such an elegant solution still had no evidential basis and proposals to demolish the intermediate truncating wall were hotly resisted by English Heritage until, by a stroke of luck, John Palmer’s plans were discovered and recognised by David McLaughlin, conservation architect with the city council, as the missing link clearly identifying both stages of construction.

With the pump room form understood, the question of the appropriate shape and form of the new pool was still as yet unclear. One criterion was that the new structure had to be introduced to provide new and uncontaminated surfaces to retain the pool water (Naegleria fowleri is known to inhabit contaminated structures indefinitely, merely waiting for suitable conditions to revive.) In addition, as discussed above, no breach of the 19th-century concrete structure could be countenanced owing to the delicate and unquantifiable condition of the existing structure. This precluded at a stroke any thoughts of trying to replicate Baldwin’s pool, even in outline.

|

|

| The focal spring feature with Baldwin's fragment to the right |

THE NEW OVAL POOL

The second eureka moment occurred when considering how the form of Palmer’s oval pump room could be suggested without compromising the conjectural reconstruction debate and holding true to the requirement of a contemporary solution. The oval pump room was seen to have generated the semi-circular colonnaded north end, and so a matching oval pool would also respond to the curved blind colonnade to the south east. Where these two overlapped, a secondary pool could be created, resolving another awkward design conundrum of how and where to present the spring emergence. Everything at this stage then fell into place as the overlap or ‘cross’ of the ovals occurs symmetrically in the plan form and on the central axis of Bath Street itself. When it was realised that this was the ancient and highly symbolic form of a vesica piscis, the spiritual box was ticked as well.

To summarise, all the original historic fabric had been repaired, consolidated and retained. The materials palette of glass, stainless steel and stone had been established by Grimshaw, and new work was to be identifiable. A new wall containing a disabled-accessible toilet has now been built to mirror an existing wall to the north east. Palmer's oval pump room has been recreated in a virtual sense by the entrance roof and floor pattern. The Bath Street axis has been resolved in the spring feature pool and overlap with the pump room and pool axis. Baldwin’s fragment to the west and south has been retained and partially protected by a curved stone memorial bench in front. The central doorway to Baldwin’s original serpentine elevation, blocked by Palmer when relocated on an axis with Bath Street, has now been opened up to reveal the view of the spring head. Translucent screens have been introduced here and in the southern arched window for use when the pool is occupied by bathers, but may be removed at other times to make visual connections with the surrounding area.

THE SPRING FEATURE

The design of the spring feature posed as many problems as any element. The spring water has to rise into the atmosphere under its own head, untreated and untouched by metal, so that it appears to feed the pool. It must then be taken under the street to the main treatment plant within the depths of the new building and return to the Cross Bath for use by the public. (Spring bathing water does not require treatment, but it must be cooled to a comfortable 35°C, and it must be treated for contamination from outside and from other bathers.) The spring source is continuously monitored for contamination, and for any variation in temperature and volume flow rate, both of which remain remarkably consistent at around 44°C and 192,000 litres per day.

The commission was won by William Pye. Two tall flank columns run with spring water and are internally illuminated to give patterned light to the canopy above. They frame the central polished dish which receives the spring water, untreated and uncontaminated, as it flows over the hemispherical dome, and is animated by the natural bubbles rising from within.

DUCK TROUBLE

The constructional phase of the project was dogged by seemingly endless problems, as has been well reported elsewhere. However, the unique nature of this undertaking can be demonstrated by one particular episode when the whole project was put in jeopardy as construction ground to a halt owing to some nesting ducks that had got under the protective netting of the Cross Bath. All was thrown into confusion as the sanctuary of this WWF-acknowledged Sacred Site was invoked.

Ultimately, the determination to see the project through of the local council and the Dutch operator, together with the project team, are now paying dividends. This very popular scheme has so far won awards from the Georgian Group and the Civic Trust.