Design in the Historic Environment

Michael Davies

|

|

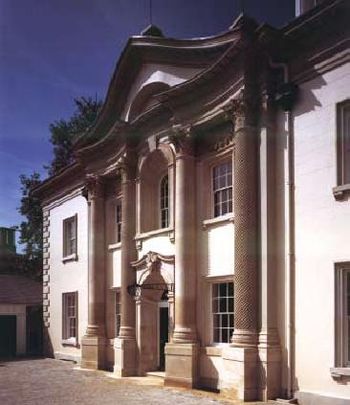

| The Corinthian Villa by Erith & Terry: a new house in an historic style which works because of its accuracy, attention to detail and exquisite craftmanship |

On this small island that is Britain it seems more difficult to build than ever. There are huge demands on our towns, cities and countryside. A growing population and a seemingly endless army of experts ready to shoot down any hint of development, protected by mountains of preservationist policy which seem to stifle the very idea of imaginative design. So it is not surprising that when development is proposed in an historic environment these difficulties are magnified many times.

It is right that we should be concerned for our historic buildings. Lessons have been learned from the 1960s and '70s where a Brave New World threatened to remove all traces of our past. Since then the planning control system has been developed to try to ensure that the many historic buildings and areas which have survived throughout the country are conserved, not lost or damaged, and that any new development in these areas is sensitive to its historic environment. Unfortunately, the word 'sensitive' is a very subjective term coined by conservationists; nevertheless it is an excellent watchword, serving to raise awareness of the issues at stake. But have we overreacted to the mistakes of the '60s and '70s? Have we become too conservative, losing the confidence to build well in an historic context? For some people, one of the most appealing aspects of an historic building is seeing the various phases of development, not least because they help to show how the building has evolved over time, each adding to the building in its own style. So, if we were to add to the past by building an extension, or by making minor alterations to the inside or outside of an historic building, or simply by creating a new building next door, how should we leave our mark, and how will our buildings be judged by future generations?

STYLE, SCALE AND PROPORTION

The criteria of 'style, scale and proportion' generally represents the basis upon which design in the historic environment is judged. Most design guidance will tell you that the scale and proportion of the new building should be subservient to the old. There should be respect for the historic status of the existing, and designers should adopt a sense of awareness to the historic circumstance of their surroundings. This is a sound basis upon which to design. The scale and proportion of new buildings can have a varied affect upon the neighbouring buildings. If the new building dominates the existing, the historic character might also be diminished, while a relatively indifferent design might heighten the historic qualities of the existing building. However, these prescriptions for 'good' design are no substitute for the skill of the designer. Even the most subservient design can ruin the appearance of a beautiful old building or street. If only all buildings could reflect the hand of skilful design.

QUALITY COUNTS

In recent years much has been written about the quality of architecture. Prince Charles popularised the debate in 1988 with his Vision of Britain - a passionate cry from the heart with which the British public could identify, if not the professional fraternity. Here the Prince searched for the answer to why all the buildings he liked were old and none of them modern. The Vision of Britain did go on to identify some good modern examples, but the clear message was one of tradition and the past. This led to the Prince of Wales building a new village in Dorset as an exemplar of his gospel. Walking into Poundbury is like walking into the past. However, if you compare this with another new town - Milton Keynes (planned upon a modern grid), the appeal of Poundbury becomes clearer. So it is not surprising that we hark back to the comfort of what we know and love - it is safe and enduring; it satisfies our needs. But is this the answer? After all, most villages and towns were built up over many years and evolved their own peculiar character.

We often struggle to find an identity in a style as if this is the panacea for good design, and yet some of the most outrageous designs have succeeded in the most sensitive context. The Sagrada Familia, Gaudi's inspired cathedral in Barcelona, is outrageously original and a triumph of modern design: the quality of its design speaks volumes and it dominates its setting. Will the same be said of Daniel Libeskind's extremely bold extension to the Victoria & Albert Museum? The success of quality is often the test of time. What we might see as a success today might not be seen in the same light in the future.

John Ruskin had the foresight to realise the endurance of good quality by proclaiming 'When we build let us think we build forever' (the Lamp of Memory).

Edward Cullinan believes it is a lack of aesthetic sensibility by planning committees, government agencies, and pressure groups which have accepted that new buildings should reflect the old buildings surrounding them, resulting in a mild mannered architecture composed of simplified or watered down components, lifted from the past. He believes that this insults both the past and the present and enhances neither.

A MODEL

There is therefore more than one way to design in the historic environment, and much will depend upon other influences, such as the aspirations of the building owner, cost, the aesthetic sensibilities of the planners, the skill of the designer, and so on.

1)

Pastiche |

Richmond

Riverside Development by Erith & Terry A very skilful approach that requires an academic understanding of the period. Every detail and choice of material is an essay in the historic language of architecture. This building could easily be mistaken for the 'real thing', but if the detail and materials are watered down it will result in a poor imitation. |

||

|

|||

2)

Traditional |

Televillage,

Crickhowell by Powys County Council architects A safe option that is often encouraged by the planning authorities, as it tends to follow the local vernacular. Much of its form, detailing and materials are borrowed from the past but have evolved into a watered down version. It takes little imagination and skill to produce a solution that 'fits in'. If handled sensitively it can produce some pleasing results. |

||

|

|||

3)

Subtle |

Cathedral

Library extension, Hereford, by Whitfield Partners Probably the most universally accepted approach to design in the historic environment. It is a conservationist's approach, where a light touch is required. Note the use of historic references and traditional materials, yet it is still subtly modern. It combines a respect for its surroundings with subtle detailing that confirms its place in the present. |

||

|

|||

4)

Modern |

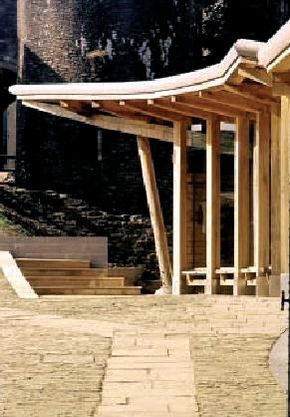

Visitor

Centre, Caerphilly Castle, by Davies Sutton Architecture Ltd This approach displays a modern design that is clearly of its time, but still respects its historic environment. It will have a strong and clear philosophy which draws its inspiration from the past. It might assemble local traditional materials in a modern way or, use modern materials in historical forms. This requires a skilful hand and a good understanding of its historical surroundings. |

||

|

|||

5)

Arrogant |

Extension

to the V & A, London, by Daniel Libeskind The tension created between old and new can be quite breathtaking, but requires great skill and vision to pull it off. A bold approach that needs an enormous leap of faith by all those involved, from client to planning authorities. This may be considered a 'building of the future' and will inevitably receive mixed reviews. |

||

|

|||

The model at the bottom of the page attempts to set out five different approaches to design and gives examples of real buildings which might arguably fall into each category. The model can be used as an initial discussion tool to visualise and debate the various approaches and decide which one is suitable.

As in age and politics, design for the historic environment is polarised by two extremes: the very historic and the very modern. Then everything else fits somewhere in between on a sliding scale, and it is possible to place any building on the scale to determine its stylistic relationship with its surroundings.

The 'Pastiche' approach (1) is where a building or extension is created as an historic essay based upon academic learning. Invariably this is very difficult to pull off, and there are nearly always some concessions to modernity. In the case of our example at Richmond, modern open plan offices sit behind a very fine replica façade; its downside is that large expanses of suspended ceiling are easily visible when standing outside the building.

The 'Traditional' approach (2) is probably the most common and is arguably that which has 'watered down components lifted from the past'. It could also represent the modern vernacular of speculative house building.

From the other end of the spectrum, the 'Arrogant' approach (5) is immensely confident and pays little regard to its historic context. For this to succeed requires the most skilful designer, and many people would always find this unacceptable.

The 'Modern' approach (4) provides an unambiguous building clearly of its time drawing its inspiration from the past and respectful of its historic context. When skilfully handled this is arguably the ideal approach.

The 'Subtle' approach (3) requires a light hand and a deft touch. This approach probably pays the most respect to its historic context and is often adopted where a quiet, gentle approach is appropriate, one which allows the historic environment to speak loudest.

There is no doubt that design, like art, is subjective, and trying to understand the meaning and the process of design is difficult, let alone attempting to prescribe what is good design, and what is acceptable. Sir Henry Wotton (1568-1638), translating from the writings of the first century Roman architect Vitruvius, passed down an enduring interpretation of what represents good design: 'In Architecture, as in all other operative arts, the end must direct the operation. The end is to build well. Well building hath three conditions - commodity, firmness and delight'.

It is therefore left to the individual to decide how to approach design in the historic environment. But beware the opinions of others. Like many other things in life, it is the diversity of opinion and personalities that enrich our lives, and so it is with architecture. The historic environment is capable of absorbing the many personalities of our new and old buildings, and there is room for all the many different approaches to design in the appropriate place. However, the one thing that must prevail is quality - quality of design and quality of materials. We should not just see it as 'building'; we are creating 'architecture'. Ironically, it was the most famous modernist of all who captured the meaning of design and beauty in architecture when he said: 'You employ stone, wood and concrete, and with these materials you build houses and palaces; that is construction. Ingenuity is at work. But suddenly you touch my heart, you do me good, I am happy and I say: "This is beautiful". That is architecture. Art enters in' (Le Corbusier, 1927).

VISITOR CENTRE, CAERPHILLY CASTLE

|

At Caerphilly Castle, the new visitor centre has provided a solution to placing a new building in the grounds of a scheduled ancient monument. The building is unashamedly modern and of its time, and yet it is sensitive to its surroundings by looking to its past for inspiration. While the castle is constructed of massive stone walls, it once also contained other structures of timber frame construction, such as small buildings, fighting platforms and lean-to roofs or pentices. Being of timber, these structures have long since rotted away, although Cadw has rebuilt for interpretive purposes several siege engines and a hourd, a timber structure which protected people on the castle walls from arrows. The dominating oak framed structure of the new building fits well within this theme, and nestles against a protective stone wall near the entrance to the castle. As the new building was never part of the original castle, it is alien, an invader, and as such its roof can be seen rising up to attack the inner gatehouse, reintroducing drama to a once dramatic environment in more dangerous times.

The extensive use of timber also satisfies another 'conservation' issue - one of sustainability and the environment. Timber from a locally managed resource has a very low embodied energy factor and can ultimately be recycled when the building has expired. By placing the building against the north wall and facing directly south it is protected from the cold northerly winds, and the large area of glass generates large amounts of free heat from the sun. The dark natural slate floor absorbs the sun's heat and radiates back into the building when the temperature drops. The underfloor heating is operated from a heat pump, which is connected to the vast moat surrounding the castle, extracting more clean, free energy from the environment.

Recommended Reading

- John Warren, John Worthington and Sue Taylor (eds), Context: New Buildings in Historic Settings, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, 1998

- Quality in Town and Country, Department of the Environment discussion document, July 1994

- Power of Place: The Future of the Historic Environment, The Historic Environment Steering Group, English Heritage, 1994

- HRH The Prince of Wales, A Vision of Britain, Doubleday, London, 1989

National Planning Policy Guidance

- PPG01 General Policy and Principles, February 1997

- PPG07 Countryside: Environmental Quality and Economic and Social Development, February 1997

- PPG15 Planning and the Historic Environment, September 1994