Earth Buildings and Their Repair

Dirk Bouwens

|

||

| A new extension contructed with cob walls, rendered and limewashed. As a thermally efficient building material which involves minimal energy-use in its production, earth is attracting renewed interest for the construction of new buildings and extensions. |

Most people associate buildings with earth walls with Africa, Arabia and South America. Yet, despite our damp climate, there are thousands of earth buildings in the United Kingdom, some of which are over four hundred years old.

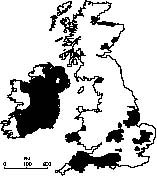

Each region (see map) tends to have its own form of construction dependent on the nature of the materials available locally. The principal forms of earth building include:

Cob: The thick cob walled houses in the West Country are probably the best known of all earth walled building types. Their thick walls are made by piling a mixture of subsoil and straw, about 600mm thick, on the wall and paring the rough edges flush with the wall. The next layer is put on when the previous work has dried enough to bear the weight. This method of building extends east as far as Basingstoke where the subsoil used is mainly chalk. Similar forms of construction can be found in the South West and in north west Wales.

Between Oxford and Aylesbury thin walls were constructed using the cob technique, where it is known as wychert (or whitchert), meaning 'white mud', and in the Midlands the local earth is used to build in the same way.

To the north, on the Solway Plain, and on both sides of the border, walls are built with the continuous cob method in which the subsoil is placed in thin layers alternating with layers of straw. Because the layers are so thin, by the time one layer has been put right around the building the previous layer has dried sufficiently for the building work to continue.

Clay-lump or 'Adobe': The universal mudbrick, adobe is found only in East Anglia in the area east of the A1 and south of the A47, where it was introduced, from abroad, around the end of the 18th century. For about 100 years it was the principal walling material for every sort of building on the chalky boulder clays of Norfolk and Suffolk. Although adobe was reported in Perthshire before it was introduced in England, none has been found. Construction is similar to brickwork with regular bonded courses, but the dried blocks of adobe or clay-lump are much larger and are usually laid in a mortar of fresh earth or clay.

|

||

| Areas of the British Isles in which earth buildings are commonly found |

The roofs of earth buildings are usually hipped, not gabled, because of the difficulty of providing the necessary restraint for a gable wall. Rafters are carried on wall plates positioned over the centre of the wall and the spaces between the rafter feet are filled with subsoil.

Chimneys are usually constructed of brickwork above the roof, although the flues below are often of clay-lump. Where there are no chimney pots, water is liable to get inside the chimney and erode the top of the clay-lump. Many brick flues were lined with subsoil and some had their brickwork laid in earth mortar.

Openings in walls are bridged with wooden lintels and often have blocks of wood built into the reveals for fixing doors or windows. In clay-lump buildings the windows and doors were built in. Because monolithic walls shrink as they dry, the openings were formed as the wall was built and the doors and windows were fitted afterwards.

Many clay-lump houses have one or more elevations faced with brickwork which was either built with the house or put on as an improvement later. The brickwork was fixed to the clay-lump with bands of hoop-iron which were nailed to the clay-lump or were built into the mortar joints. In time these ties rust and fail. They can be replaced using remedial ties designed for cavity walls.

Wattle and Daub: The most common form of non-load-bearing earth construction is wattle and daub, which has been widely used to infill the panels of timber-framed buildings. Like all the other forms of earth-based building materials the 'daub' is made of a subsoil which must contain a small proportion of clay mixed with animal or vegetable fibre. In this case the earth mixture is supported by an interwoven lattice of sticks and laths (the 'wattle').

A variation of this technique can be found in Lincolnshire where there are a number of houses with mud and stud walls. In this case the mixture of straw and subsoil is placed around and between earth-fast posts. These houses are small and generally well recorded, well repaired and fiercely conserved.

Others: In addition to the techniques described above, there are numerous variations and hybrids, such as shuttered clay (a form of cob in which the plastic subsoil is placed between boards) and pisé de terre, in which shuttered earth is rammed in thin layers to form an extremely dense, hard material. In Scotland, walls can be found which are made using grass turves and peat turves.

DAMP AND DECAY

The strength of earth walls is proportional to their moisture content. At a moisture content of 13 per cent of its dry weight the strength of the material falls to a point where it can no longer resist the pressure exerted by an average wall (c. 0.1N/mm2). At this level the wall may collapse. Damp is usually caused by poor alterations, inadequate maintenance, or a lack of ventilation.

Rising Damp:Most earth buildings have shallow rubble foundations with footing walls of brickwork or rubble masonry, varying from about 150 - 1200mm in height. Rising-damp seldom crosses from the footing wall into an earth wall. However, where a damp course is necessary, it should be inserted in the footing wall to avoid any damage to the earth construction.

Where earth walls have no footing walls, rising damp is more likely to be a problem, but in these cases, damp-proof courses which provide a barrier should not be used, as they prevent the drying of the part of the wall below by isolating it from the wick effect of the wall above. This can lead to the collapse of the wall as the moisture level increases. Alternative methods of reducing damp should be introduced on the advice of a specialist, such as improvements to land drainage and the rapid removal of surface water from around the building when it rains.

Impervious Coatings and Renders: Earth walls are traditionally finished externally with lime or earth renders and internally with similar but finer earth or lime plasters. Renders with a cement content of more than 10 per cent should not be used as they are not vapour permeable, and inevitably trap moisture within the structure. They also provide a cold surface on which condensation will form within the structure and, furthermore, cement expands when warmed (it has the same coefficient of thermal expansion as steel) while earth tends to shrink. As a result, differential thermal movement causes cement renders to crack, allowing water to enter. This moisture, combined with condensation on the back of the render, percolates to the base of the wall where it accumulates, causing the earth wall to deteriorate.

Failures due to the use of cement renders have been dramatic, involving the collapse of large sections of walls. Painting the exterior of the building can have the same effect, as many modern paints trap moisture in the wall. This sort of damage may not be covered by normal household insurance policies. Therefore, where repairs are required, a lime or earth render should always be used which matches the original as closely as possible, and when dry, they should be painted with limewash which is not only the traditional finish but also vapour permeable.

EARTH MIXTURES FOR REPAIRS

Because the subsoil varies so much, there are no definitive recipes for render mixes. However, all earth mixtures contain two essential ingredients in water; an aggregate such as sand or chalk, and clay which coats the aggregate particles and acts as a binder. Other ingredients might include set retardants such as hydrated lime, and fibre reinforcements such as straw and ox hair.

The clay content of the render shrinks as it dries and cracks develop. Unlike the cracking of cement renders, these cracks are essentially an aesthetic problem only, because the whole of the render is porous and water can therefore evaporate as readily as it is absorbed. The earth mixture is therefore selected with the aim of decreasing the size of the cracks and increasing their number; ideally there should be countless invisible cracks. Reducing the amount of water in the mixture reduces the cracking but also makes it more difficult to apply. By adding any sharp sand, straw, chalk or hydrated lime, the proportion of clay in the render is reduced and the cracks reduced in size. Chopped straw, produced for chicken litter, is ideal because more of this type of straw can be mixed in. Chalk (agricultural lime) should be graded 6mm down (ie sieved to include only particles of 6mm diameter and less). Adding hydrated lime also reduces the size of the cracks by slowing the rate at which render dries. Deflocculating agents (which affect the polarity of molecules) may be used to reduce the amount of water necessary to make the render workable. These include urine, isinglass, fresh cow droppings (from a milking parlour), and waterglass.

Any scheme of rendering must start with a trial patch which is best carried out on a sheltered elevation in case it can be kept, even though the mixture has to be improved. Quite severe cracking can often be re-worked by brushing the face of the wall with a stiff broom before starting the rendering.

A dry wall will suck the moisture from a render mix in moments. Therefore, many operatives wet the wall with a hose before rendering to reduce the suction; while others prefer to make the mix very wet to enable it to be reworked later. Clay renders perform best if they are forced on to the wall. More pressure can be exerted if the rendering starts at the bottom of the wall. If there is any doubt about the condition of the surface of the wall being suitable, then lime renders, in particular, should be put on to a stainless steel or other non-ferrous metal mesh which is fixed with spring head sheeting nails.

Minor damage to earth walls can be patched. However the size of holes which can be patched is limited by the shrinkage which will occur when large volumes of new material are applied in a wet form. Large holes therefore have to be filled in layers; each one being left to dry before being scored to provide a mechanical key before the next is applied. The hole should be over-filled and finally the surface is cut back, or 'pared' to the line of the wall. These techniques are fully described in several publications and it is probably better to contact the local Earth Building Association before attempting them for the first time.

Larger repairs are made by cutting out the damage and rebuilding using cob-blocks or clay-lumps laid in mortar. Cob-blocks are made for sale in the West Country and should be made of subsoil similar to the wall to be repaired. The material which is cut from the wall can be crushed and riddled, to remove large stones, and used for the mortar in the repairs. When cob-blocks and clay-lumps are laid in wet mortar the moisture in the mortar is absorbed very quickly into the blocks so the work is not delayed while the mortar dries.

Wattle and daub often contains more archaeological evidence than the timber frame, and it can be quickly and cheaply repaired. Yet it is often discarded during works.

The daub should be salvaged and reconstituted to a paste with added barley straw cut about 100mm long. Tie hardwood coppiced sticks (20-40mm diameter) to the frame in the same way that the originals were tied, spaced so an open hand will go between. The County Conservation Officer will know where to get coppice sticks. Working on both sides, press the daub through the wattle to cover it to a 25mm thickness. As the daub dries it will pull away from the frame. If another coat of daub or plaster is to be put on, prick a key into the surface otherwise press the daub with a float to close the gap.

Rats burrow in earth walls especially if they are damp and near a source of food. Grout with an earth slurry only when confident that the extra moisture will not weaken a wall already weakened by the burrows. Burrows are probably better cut out so new blocks can be put in.

~~~

Further Information

- Advice on problems to do with earth buildings can be obtained by contacting your local authority conservation officer or Earth Buildings Association

- Devon Earth Buildings Association, Environment Directorate, Devon County Council, County Hall, Exeter EX2 4QW

- EARTHA, East Anglian Earth Buildings Group, Paperhouse, West Harling, Norfolk NR16 2SF

- East Midlands Earth Structures Society, The North Wing, Harrington Hall, Spilsbury, Lincs

- Centre for Earthen Architecture, University of Plymouth, School of Architecture, Notte Street, Plymouth, Devon PL1 2AR

Recommended Reading

- Hugo Houben and Hubert Guillard, Earth Construction: A Comprehensive Guide, Intermediate Technology, London, 1994

- Larry Keefe, The Cob Buildings of Devon 2: Repair and Maintenance, Devon Historic Buildings Trust, 1993

- John Norton, Building with Earth: A Handbook, Intermediate Technology, London, 1986

- Gordon Pearson, Conservation of Clay and Chalk Buildings, Donhead, Shaftesbury, 1992

- Jane Schofield, Lime in Building, Black Dog Press, Crediton, 1995

- Bruce Walker and Christopher McGregor, Earth Structures and Construction in Scotland, Historic Scotland, Edinburgh, 1996