Lest We Forget

Stained Glass Memorial Windows of the Great War

Jonathan Taylor

|

|

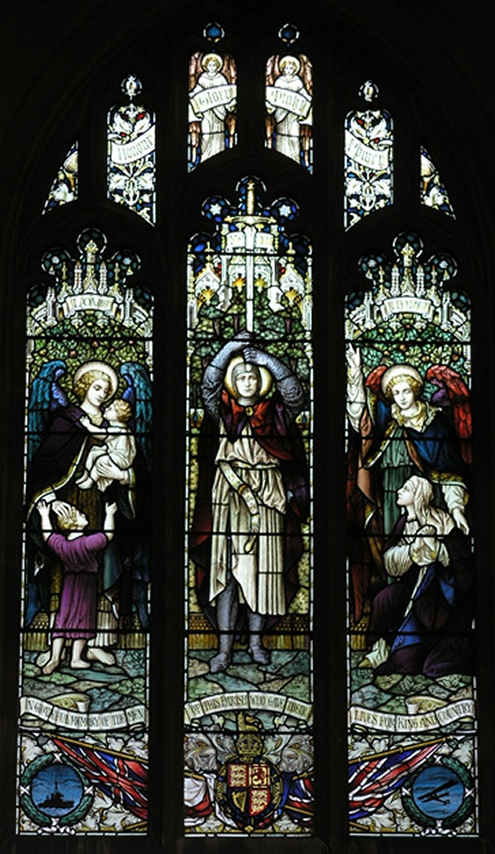

| A memorial to the parishioners of St Luke’s church, Bath: the style owes much to the medieval designs of William Morris, but the two roundels at the bottom show a battleship and a plane - images of modern warfare |

The United Kingdom of Britain and Ireland suffered three million casualties in the First World War (WWI). Memorials to this missing generation took many forms. In addition to the more visible monuments in city centres, towns and villages, a surprisingly large number of stained glass windows were installed and dedicated to their memory.

These church windows follow a tradition of memorial construction in places of worship that is perhaps as old as churches themselves. Many celebrate the lives of all those who died in a local community, as at St Luke's, Bath, illustrated here. At St Chad's Roman Catholic Cathedral, Birmingham, the memorial window (by Hardman & Co, 1919) has a triptych below it containing the relics of the fallen, including rosaries, photographs, buttons, badges, prayer books and identity books. Some memorial windows were donated by locally-based regiments, companies or organisations which had lost members, such as the South Metropolitan Gas Company memorial window in the retro-choir at Southwark Cathedral, London (also by Hardman & Co, 1923), which is illustrated further down this page. Others celebrate the lives of family members, such as the Wilson family memorial window in St Mary's, Chippenham (by Christopher Whall, 1919), dedicated to the memory of the three sons of Mervyn and Helen Wilson; Captain Herbert Wilson, killed in action at the age of 29 in Mesopotamia in 1917, Evelyn of the East Yorks Regiment killed in Hulluch, France in 1915 aged 23; and their younger brother Mervyn, a captain in the Wiltshire Regiment killed in action seven months later at the age of 22.

Dedications like these, to a generation lost in the Great War, are commonly found in cathedrals, churches and chapels of all denominations, from big cities to small country churches, throughout the country. The UK National Inventory of War Memorials (www.ukniwm.org), which is based at the Imperial War Museum, currently lists 3,000 stained glass war memorials (1,800 relating to WW1), mostly in churches, and its research continues.

|

|

|

| Above left: detail from centre of a three-light window at Southwark Cathedral, London by Hardman & Co showing the presentation of Christ in the temple. This window was presented by the South Metropolitan Gas Company in memory of 386 employees who died at its works nearby and, above right: single light memorial in the church of St Lawrence, Brundall by Morris & Co. The amount of ‘white’ glass reflects the fashion for lighter windows, but this was otherwise a very traditional design (Photo: John Salmon) | ||

As well as being of enormous importance to the descendants of those remembered and to the wider community, these stained glass windows have now acquired great historical importance as products of momentous historic events, providing a physical connection with the past.

Like all historic stained glass windows, they are also important as historic works of art, illustrating the aesthetic tastes and sensibilities of a particular age, and providing rich and colourful images. Furthermore, many of them contain images of modern warfare that are not only poignant, but also captivating, not least for their incongruity in an ecclesiastical setting.

The period which followed WW1 was a particularly interesting one for art and architecture, with new approaches to design emerging. These changes are particularly evident in the design of stained glass war memorials, which include sumptuous, if a little out-dated Gothic Revival designs, as well as a few more forward-looking examples, some of which clearly display Art Nouveau influences. Those of the Second World War (WW2) illustrate how these trends developed, although often still clearly influenced by the Arts & Crafts tradition.

TRADITIONAL GOTHIC REVIVAL DESIGNS

Many

of the studios which pioneered the development of Arts & Crafts

stained glass flourished in the period which followed WW1. These

companies were firmly rooted in gothic imagery, a style ideally

suited to the gothic tracery of church windows whether medieval

or Victorian, and their memorial windows are often indistinguishable

from other church windows

to the casual observer.

|

|

|

|

| The Wilson family memorial (top, with detail below), at St Andrew’s, the parish church of Chippenham, Wiltshire to its three sons killed in WW1: the poses of the four archangels remain formal, but the gothic tracery and flat panel decoration which typically surrounds biblical characters in Gothic Revival designs has here been swept aside by Christopher Whall’s explosive use of colour and form. |

Two three-light memorial windows in the retro-choir at Southwark Cathedral typify this approach. One of these shows the presentation of Christ in the temple (see illustration, left), flanked by Simeon and Elizabeth on the left, and 'wise men travelling' on the right. This window was presented by the South Metropolitan Gas Company in memory of 386 employees. The other, which is similar, stands next to it and has the Nativity at its centre. This window was donated by Oxo to commemorate the lives of its employees who died in WW1. Typically the windows contain symbolic icons for the informed observer. The wise men, for example bear a palm symbolising martyrdom, and a candle symbolising faith.

The windows were designed by Donald B Taunton of John Hardman & Co in 1921. Hardman's is the stained glass studio most closely associated with AWN Pugin, one of the main pioneers of the Arts & Crafts movement.

William Morris & Co, another leading light in the development of Arts & Crafts stained glass work, also designed many stained glass war memorials after WW1. William Morris, who founded the company in 1875, had died in 1893, and Burne Jones, the artist most closely associated with the company's stained glass designs, had died in 1898. Nevertheless, his designs continued to be reproduced for many years afterwards.

In many of these otherwise traditional designs, small insets were incorporated, showing images of war, usually in grey, or regimental standards, such as the picture of a bi-plane in one roundel and a picture of a battleship in another in an otherwise fairly conventional Gothic Revival window in St Luke's, Bath. Regimental motifs are also often incorporated in the same way.

NEW APPROACHES IN A GOTHIC VEIN

By the early 20th century a number of smaller studios had become established, generally based on individual craftsmen or women. It was these studios that now began to challenge the supremacy of the large companies.

Two of the early pioneers were the architect ES Prior who developed slab glass in 1889 and Christopher Whall (1849-1924) who used the material so creatively. Slab glass, or 'Prior's Early English glass' as it was also known, was designed to emulate the luminosity and varied colouring of early medieval glass. It was made by blowing glass into a rectilinear box and then cutting off the sides. This yielded flat panes of uneven thickness, often streaked with colour. Whereas the prevailing style of glass relied on meticulous draughtsmanship and line control to create rich backgrounds of flat surface decoration such as gothic mouldings or foliage, the new glass could be used to create backgrounds with a more abstract pattern, as in the St Pancras roll of honour (illustrated below), or combined with lead alone to create bold and dramatic effects such as the wings of the four archangels at St Andrew's, Chippenham (see illustration, left).

Arguably Christopher Whall's greatest contribution to the development of stained glass was to return to the principles of Morris and Ruskin, and particularly to Morris's emphasis on craftsmanship. Unlike the established companies, where design and production had become separate aspects of the same business, Whall and the new generation of Arts & Crafts artists tended to take control of all aspects, experimenting with production methods to create the effects they required.

Secondly, Christopher Whall’s approach to pattern and figurative form, which is also evident in the work of others, including Louis Tiffany in America in particular, heralded a fundamental shift in philosophy. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, stained glass artists in Britain endeavoured to create ever more realistic images. Great pains were taken to create natural folds in the robes, and the advent of photography and fine wood engraving encouraged artists to look again at light and shade. The faces of the archangels (above left) follow this approach, but other elements are more representational, reflecting the gradual absorption of Continental ideas, and the influence of impressionism.

As the dominance of the Arts & Crafts studios continued to decline, more individual approaches emerged, some directly influenced by Whall, such as the group of artists in Ireland called An Túr Gloine (Tower of Glass), others by a more free interpretation of the Arts & Crafts philosophy. One common thread is the increasing use of lead and coloured glass alone to create patterns and shapes; another is the development of bold, loosely drawn lines to create characterful images often combined with heavy leading, as in the work of Scotland's east coast school led by Douglas Strachan.

IMAGES OF WAR

Although small and inset images of war are quite common in WW1 memorials, as at St Luke's, Bath, it is less usual to find soldiers and other military figures appearing in Gothic Revival scenes. An exception is Ninian Comper's window at Ufford, Suffolk. Another is a window by the studio of Jones and Willis at St Clement's church, Terrington, Norfolk, which depicts a WW1 soldier lying at the foot of the Crucifixion, with pre-Raphaelite angels surrounding the Cross.

|

|

|

| Above left: a detail from a memorial window by Hugh Easton in the church of St Peter under Cornhill in the City of London. The artist uses soft shading to create natural forms and simple realism, and cartoon cut-out characters to tell his story – in this case of WW2 soldiers on a tank witnessing the Resurrection. Above right: a detail from a window at St Mary’s Felmersham, Befordshire (1951) in which the artist Francis Spear uses bold, loosely drawn brush lines to create highly stylised images, following in the Arts & Crafts tradition. | ||

One of the most interesting examples in this category can be seen at St Mary Magdalene's Enfield in Middlesex by James Clark (1858-1943), which also shows an image of a soldier lying on a battlefield at the foot of the crucifixion (illustrated below). Here, however, the scene crosses from one light into the other, with the soldier's body lying across both. The lower part of the scene is dark and naturalistic, but in the upper part the leading takes on an almost abstract composition, bearing no relation to the sky, and Christ's legs run across the lines, as if drifting in and out of focus. The colours too verge on the surreal, rich with purples and touches of pink conveying the idea of a vision.

|

|

|

|

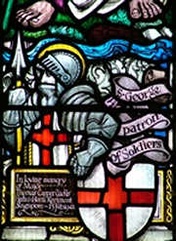

||

| Top left: a detail of Ninian Comper’s WW1 memorial at the Church of the Assumption, Ufford, Suffolk (1920) (Photo: Simon Knott). Above left: Detail of one of two memorials at the church of St Pancras, London. The knight stands at the top of a roll of honour, and the design is clearly heavily influenced by the Art Nouveau. Above right: St Mary Magdalene, Windmill Hill, Enfield. In this WW1 memorial James Clark conveys the idea of a vision through the use of colour and swirling lines of leading (Photo: John Salmon) | ||

Images of war rarely extend to cover the whole window, but there are notable exceptions. Some of these remain within a traditional framework, with separate images in each light, and may even have gothic tracery around them, as in the rather gory war scenes in the three window WW1 memorial at St Mary the Virgin, Swaffham Prior, Cambridgeshire, which capture the horror of trench warfare and show mortar shells exploding. This new realism is taken to greater artistic heights after the Second World War by Hugh Easton in particular.

Such designs may seem shocking and incongruous in a place of worship. However, they very forcefully illustrate the link between the church and its community. Church buildings and their fabric are the product of social and political issues, whether national, local or personal.

The importance of the role the church has played in the fabric of society and in the lives of ordinary people, is nowhere more graphically illustrated than in the memorials to those who died in WW1.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- Michael Archer, English Stained Glass, the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, 1985

- David Beaty, Light Perpetual: Aviators’ Memorial Windows, Airlife Publishing, Shrewsbury, 1995

- Sarah Brown, Stained Glass: An Illustrated History, Bracken Books, London, 1992

- www.ukniwm.org.uk – the website of the UK National Inventory of War Memorials