New Life for Old Ruins

Michael Davies

|

||

| Blencow Hall, Cumbria: a Grade I listed fortified manor house which was converted into a luxury country hotel in 2008 (Photo: James O Davies/English Heritage) |

Extreme modern interventions in the historic environment, like IM Pei’s glass pyramid at the Louvre in Paris, were once unthinkable in the UK. In recent years we have become less conservative about adapting and altering historic buildings and more accepting of the new roles they can play in a modern society. Of course, this view is not universal: there are still many preservationists around who think that we should pickle everything that has the word historic attached to it.

Nevertheless, the concept of ‘adaptive reuse’ is embedded in current conservation thinking. The idea that redundant buildings are often redundant because their original use is no longer viable has taken root. Finding new beneficial uses for the UK’s redundant historic buildings has sometimes been a major challenge, despite the growing number of building preservation trusts around the country, supported by the Architectural Heritage Fund. When the building in question is a ruin, the problems are often far greater and the debate widens.

There is nothing new about breathing new life into old ruins. The Forum in Rome is one of the most famous ruins in the world and many of its buildings have been reused at some point. This reuse extended beyond the common practice of recycling the marble in new structures, and included the adapting of existing ruins for new uses. The Trajan Market, built in AD 107-110, was completely transformed for reuse in the Middle Ages. Sadly, the phases of medieval, and Renaissance building in the Forum were subsequently removed in the single-minded archaeological pursuit of the ‘glories of imperial antiquity’.

How should we go about bringing new life to old ruins, and are some ruins just too precious to alter? One of the main arguments for intervention is the need for continual maintenance and the heavy costs that come with it. There are very few organisations with annual budgets dedicated to preserving and maintaining huge lumps of masonry just so visitors can wander around them on bank holidays. Indeed, those few that do, like English Heritage, Cadw, Historic Scotland and the National Trust, increasingly have to take a commercial view of their building stock. But where ruins are in private hands the burden is even greater. Grants can be made available for initial repairs but it is ongoing maintenance that presents the long term challenge. It is now generally accepted that a building with a beneficial use is far more likely to survive than one that has no use at all.

|

|

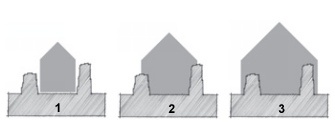

| 1. Building inside the ruin This method tends to express the ruin most fully but provides the greatest difficulty in making a weather-tight seal between old and new. |

|

| 2. Building on the ruin The ruin can be seen from both sides, but the interface between old and new often means that the ‘ragged edge’ of the ruin may be lost, as is the case with Norwich Cathedral’s new refectory building. |

|

| 3. Building over the ruin This provides the simplest and least destructive solution. The ruin is enclosed inside a museum-like building. However, the ruin is now separated from its context. |

|

|

|

| The Ara Pacis Museum, Rome |

APPROACH

There are many examples of redundant historic buildings being brought back into use, buildings that are largely intact and still present a commercially viable solution. However, ancient ruins present a different set of problems. The buildings, which have lain empty and roofless for decades or even centuries, are often scheduled monuments and therefore a more preservationist view is often thought to be appropriate.

Intervention is often a matter of degree. To what extent should the historic be compromised by the new? Can the new remain subservient to the old if the old is now in ruin and much is already lost?

There are three particular issues that are of primary consideration when finding a creative solution for ruins:

1 Juxtaposition (see diagrams, right)

The visual impact of the new structure will largely depend on its relationship with the old. For example, does the new sit within the old as if it is growing out of it: the reptile in the process of shedding its old skin? Or does the new building sit directly on top of the old structure, either bearing on it or supported on a frame so that only the outer skin rests on the historic fabric? Or does the new building enclose the ruin: a new shelter that protects the historic fabric like an exhibit in a museum, as can be seen at Richard Meier’s Ara Pacis Museum in Rome (right)?

2 style

The choice of materials and style will also have a significant impact on the ruins. Rebuilding in the same materials and style may ultimately produce a pastiche of the old building, while considerably reducing the significance of the original fabric. A more successful approach that has been used in the past involves the introduction of a seam, such as a coloured line of stones, where the old and the new meet, which clearly delineates the join. However, a more widely favoured approach is to provide a clear contrast between old and new materials and styles, thereby accentuating the historic fabric against a contemporary backdrop. Even if the new building dominates the combined structure (as at the Kolumba Museum, Cologne, discussed below), in a curious way it can also heighten the visual importance of the old.

3 Material interface

The interface between the old and the new provides all kinds of technical challenges, not least keeping the weather out. Masonry ruins, especially rubble stonework, will often have irregular edges: a less than ideal surface on which to place new material. Dealing with existing openings such as unglazed windows can also present difficulties, particularly if they are stone and partly ruined.

At Norwich Cathedral Refectory (discussed below), the approach was simply to build up the existing walls with a slightly different stone, creating a well engineered surface on which the structural glazing could rest.

|

|

| Candleston Castle, part of the Merthyr Mawr Estate in Glamorgan |

At Raglan Castle, the tops of the rubble walls were capped with concrete, with a soft membrane separating the two materials. Again, this provided a suitable level surface on which to build. A proprietary cloth fabric was used as a separating layer which allowed the new work to be totally reversible: the concrete can easily be removed at the separation layer without damaging the existing fabric.

In the process of trying to make a better join between old and new, is it acceptable to remove some of the existing fabric, particularly where it is common work and there is little to distinguish it? Alternatively, is there a tendency to be too precious about each and every stone? This represents an ongoing dilemma in the management of change in the historic environment: is the approach just too conservative? Managing change is all about compromise. Bringing new life to a ruin has obvious benefits, but these must be balanced against the loss of a ruin as a piece of architectural sculpture that is in a state of ongoing organic decay, and the loss of something that appeals to our artistic and romantic sensibilities.

CASE STUDY 1: CANDLESTON CASTLE

Candleston Castle (above) forms part of the Merthyr Mawr Estate in Glamorgan, and stands adjacent to a large range of sand dunes. The building forms part of the ruinous remains of a 14th-century manor house. The owners were committed to preserving the ruin but felt they needed to find a commercial solution to funding maintenance costs after the initial repair work had been completed.

Putting a roof back on the building and giving it a new beneficial use was considered, but this would have been expensive and was not commercially viable. The estate then considered another alternative: the domestic range of the castle forms one side of a walled courtyard and although the curtain wall is dilapidated there is still enough remaining to form a significant enclosure. Using the romantic ruin as a backdrop, a marquee will be erected on the grassed courtyard space and hired out for wedding parties. This solution offers a commercial return to support the continued maintenance of the ruin, while involving minimum intervention in the structure itself. The marquee is a temporary structure so the setting of the castle is not compromised

CASE STUDY 2: KOLUMBA MUSEUM, COLOGNE

|

||

| Kolumba Museum, Cologne: the new structure is fused to the walls of the ruined medieval church that it protects (Photo: Yuri Palmin) |

This towering edifice, which almost completely engulfs the medieval ruins of St Kolumba’s Church, takes an extreme and less sympathetic approach to building over ruins. Yet paradoxically it emphasises the special character of the ruins.

St Kolumba was badly damaged during the second world war and was transformed into a memorial garden during the 1950s. With the ruins becoming increasingly surrounded by commercial development and a collection of temporary roof structures protecting the delicate archaeological excavations, the Archdiocese of Cologne commissioned Swiss architect Peter Zumthor to build a new museum to house its collection of religious art with the ruins of St Kolumba accommodated within it.

The new structure both incorporates and shelters the original. The contrasting light grey brick was developed for the project and provides a contrast in colour, in texture and in the monolithic simplicity of the massive new structure. But this is not an uncoordinated relationship between old and new: there is a subtlety to this holy alliance. Directly above the exposed ancient fabric, the weight of the new masonry is relieved by small perforations in the masonry that also admit a dappled light into the cavernous interior, where the remains of the old church lie.

The interface of the undulating rubble stonework and stone dressings of the old structure, and the small masonry units of the new brickwork, provides a workable junction for building new on old. The overall visual contrast is striking but, like many great buildings, new and old, this is one that needs to be experienced firsthand to fully appreciate the success of this approach.

CASE STUDY 3: NORWICH CATHEDRAL REFECTORY

The one-metre thick 14th-century walls of the library at Norwich Cathedral were deemed untouchable, structurally, by the Cathedrals Fabric Commission of England. As a result, designing a new £3.5 million refectory building within the ruins of the cathedral cloisters presented a delicate challenge. Michael Hopkins Architects’ modern intervention appears delightfully simple and yet captures the essence of the cathedral nave with a treelike wooden structure supporting its lead roof.

|

||

| The new £3.5 million refectory building built within the ruins of Norwich Cathedral’s cloisters (Photo: Phil Thomas/Norwich Cathedral) |

The lightweight framed structure fits inside the original ruined building and its predominantly glazed outer walls sit effortlessly on the original fabric, minimising the load placed on the ancient rubble walls, both structurally and visually. However, the large sheets of rigid glass and the random composition of the walling material, which includes flint, brick and limestone, do not sit easily together. The clever part of this junction is the subtle introduction of another masonry walling material that bridges this difficult connection. Building up the flint walls with a new yet subtly different masonry solves two problems: it provides a practical solution for a difficult junction, and it provides an identifiable contrast between the old and the new, making it much easier to read the building’s history.

Arguably, some uneasy questions remain. Has the ruin been partly obscured by the new design? Should the outline of the ruined fabric be more visible? Has the romance of the ruin been engulfed by the modern building above, the ragged outline lost under a veil? Inside, the ruin is more easily defined. Original fabric is clearly visible and has not been built over to the same degree. Overall, the effect is very pleasing and provides a bright and lively space of tremendous quality which provides the cathedral with another stream of income.

CASE STUDY 4: DOVECOTE STUDIO

Snape Maltings is a complex of Grade II listed industrial buildings, many of them still derelict. The Dovecote Studio (below) forms part of the internationally renowned music campus founded by Benjamin Britten in abandoned industrial buildings on the Suffolk coast. A general strategy for regeneration of the Maltings was developed through close dialogue with the client, English Heritage, and Suffolk Coastal planning officers.

The regeneration strategy concentrated on preserving existing fabric, with all its patina of age and use, and adding to it – where necessary – in a legibly contemporary architectural language that should be as uncompromising and industrial as the original buildings, and should age gracefully to unite with the existing structures. Literal reconstruction of the dovecote would have contradicted this strategy. Instead, the new studio was conceived in a form that reflected the shape of the original building, but in a material, Corten weathering steel, that was strikingly modern. This form was seen as a separate structure that could be placed within the shell of the existing ruin, while leaving it untouched.

Although contemporary, Corten steel weathers to a shade of rust-red almost exactly the same as the colour of Suffolk red bricks. Meanwhile, although its form echoes the shape of the old dovecote, its construction from a single material gives the new studio an enigmatic quality. The result is a building that from a distance evokes the ghost of the original structure, but, seen from close up, reveals itself as entirely new.

The Haworth Tomkins design complements the distinctive architecture of the Maltings in a way that is both sensitive and uncompromisingly modern. It solves the complex challenge of working within a fragile ruin without losing the essence of the ruin to the ambitions of redevelopment.

|

|

| The Dovecote Studio, part of the famous music campus at Snape Maltings which occupies a complex of converted Victorian industrial buildings on the Suffolk coast (Photo: Philip Vile) |

CASE STUDY 5: BLENCOW HALL

When the Grade I listed Blencow Hall (see title illustration) was acquired by the present owners, the central and south ranges were still in occupation but the two late 16th-century towers lay vacant and decaying. The south tower was a roofless ruin and had sustained a large breach in its east wall, possibly as a result of ‘slighting’ in the Civil War (partial destruction designed to deny the use of fortifications to the enemy) combined with later structural settlement. Donald Insall Associates, with local architect Graham Norman, devised a scheme to bring the towers back into use as part of a luxury country hotel, with a sensitive yet dramatic solution.

It was decided to retain the breach in the outer wall as it is part of the story of the building, and a steel frame was used to support the leaning external walls. The new glazed wall behind the breach was set back from the original walls, so that the raw edges of the broken masonry remained visible. The recreated rooms on all three levels within the south tower were designed to make the best advantage of the stunning views to the south east and they offer light open interiors that contrast with the more enclosed remaining rooms which retain their traditional windows.

Reinstating the original roof provided most of the necessary weatherproofing for the tower, leaving only the junction between the new glazed wall and the old stone walls. The new wall is well set back behind the edges of the breach with the vertical abutments being protected by the small balconies and the overhanging roof. These abutments have been weatherproofed with a compressible water resistant foam seal strip to take up the irregular profile of the rubble stonework. Apart from the consolidation of the exposed ragged edges of the masonry, there was no intervention into the masonry structure either side of the breach.

The beauty of this solution lies in the clarity of the contrast between new work and old, and in the minimal intervention to historic fabric.

WHERE OLD MEETS NEW

There is a hard commercial fact at the core of this debate: how can we continue to maintain and enjoy these structures where a subsidised purse is not available in perpetuity, and continue to promote sustainable change in our historic environment? English Heritage claims that its responsibility to provide good stewardship means that it must recognise the need to maximise commercial opportunity at its historic monuments. This highlights the fact that even those sites that enjoy the benefits of subsidy need to make better use of their heritage assets. Without subsidy the need to find a creative solution is clearly even greater.

Finding the right solution for adapting a ruin is one of the greatest architectural challenges. Not only is the form of the structure often uneven, and the materials compromised by years of exposure to the elements, but the philosophical challenges of how to approach the design and how to touch the existing fabric lightly are complex and highly contentious.

Achieving a clear contrast between new and old while ensuring a successful technical collaboration between materials is bound to present a dilemma when ancient stone meets new ambition.