The Ancient Art of the Locksmith

Valerie Olifent

|

|

| Figure

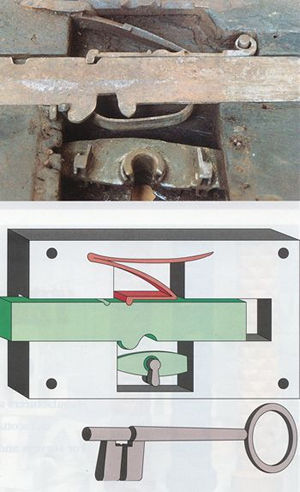

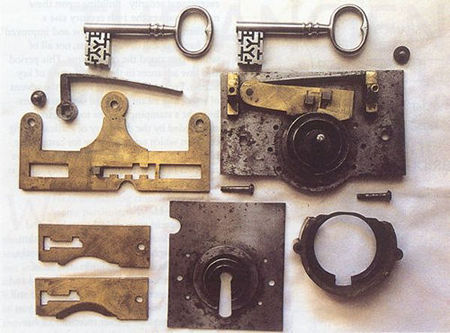

1 The Banbury Lock

Above, a close up photograph of an 18th century Banbury lock mechanism

(cap removed) from Theddlethorpe Church in Lincolnshire which is

in the care of The Churches Conservation Trust. Note the decoration

to the tumbler and spring.

Below, a diagram of the Banbury lock, showing mechanism set into

a wooden stock, and the distinctive key with a collar set within

the width of the bit.

|

When considering church locks it seems particularly appropriate that the earliest depiction of a lock should be found on a bas-relief in an Egyptian temple at Kamak dating from 2000BC. Although not immediately recognisable to modern eyes, and being somewhat cumbersome in operation, it functioned effectively. The principle, that of raising pins to create a shearline to allow movement, was rediscovered by Linus Yale Senior in 1848 and further developed and refined by his son Linus Junior between 1861 and 1865 to give the pin tumbler cylinder lock so widely used today. The Greeks are credited with the invention of the keyhole, the point of a sickle shaped implement being inserted through a small hole in the door, and, with a slight rotary motion, closing or withdrawing a large bolt A Linear B tablet dating to 1300BC, excavated in Crete, was translated.

Thus the Mayors and their wives and the Vice-Mayors and key-bearers and supervisors of figs and hoeing will contribute bronze for ships and the points of arrows and spears.

Keys are mentioned in the Old Testament, notably in Judges ch3 v25, written around 1170BC and Isaiah ch22 v22, from about 740BC. The earliest lock excavated came from the Palace of Sargon at Khorsabad in Iraq, dating from 700BC. By the time that Vesuvius erupted in 79AD, when a metal worker's shop was overwhelmed, locks had been developed and had assumed a form recognisable to modern eyes. Many have been excavated both from Pompeii and from the numerous Roman sites in Europe and the Middle East. As they were now made from metal a large number have survived. Padlocks with a spring tine mechanism were found at York when the Jorvik Viking settlement of 850 was discovered.

A small but useful source of information from this period through to medieval times comes from the art of the period; carvings, wall paintings, illuminated manuscripts and stained glass. Depictions of everyday life sometimes show contemporary locks and keys and portrayals of St Peter can be a rich source. Even the Bayeux Tapestry shows Duke Conan of Brittany surrendering the keys of the town of Dinan to William on the point of his lance. Written records start to appear in the medieval period. The surviving accounts for the refurbishment of Portchester Castle in 1385 record the purchase of locks, and in 1394 London smiths were forbidden to make keys from an impression 'by reason of the mischiefs which have happened'. In 1411 Charles IV of Germany created the title of 'Master Locksmith' and by 1422 the London Guilds included the 'Lockyers'.

Some locks still in use do survive from this time, in historic college and university buildings as well as churches, but most are in private collections or museums. In the Victoria and Albert Museum you can see the 'Beddington Lock' which accompanied Henry VIII on his travels through the kingdom, being installed on his chamber door wherever he stayed to ensure his security and privacy. In the accounts for July 1532 is written 'Item - paid to the smythe that carryeth the lock about wh the King in reward VIIsVIc'. After the distress of the Civil War and the privations of the Commonwealth, the Restoration of the monarchy in the 17th century saw a flowering of architecture and the arts, which extended even to locks and keys. Locks were made of an intricacy and beauty rarely equalled, often with the mechanism as highly decorated and engraved as the case.

|

|

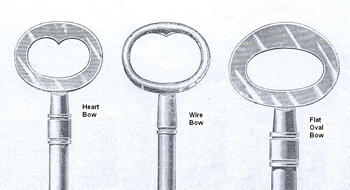

| Figure 2 The parts of a key | |

|

Even until the mid 18th century and beyond, when elegance ruled, a degree of decoration of the mechanism sometimes persisted, enclosed within the plain, simple lockcase. The latter half of the 18th century saw the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution. In 1778 Robert Barron took out a patent to improve the security of locks, earning him the appellation 'Father of the English Lever System' (see Figure 5). Some of the locks with his 'modern' and distinctive mechanism and keys can still be found in churches. In 1784 Joseph Bramah, the inventive Yorkshireman, patented the Bramah lock, an entirely new concept in lock design which utilized a series of sliders in a circular pattern to provide exceptional security. Building upon these major advances the 19th century saw a proliferation of patents for 'new and improved' mechanisms and developments, not all of which have stood the test of time. This period also saw advances in the manufacture of key blanks. Previously all hand forged, the advent of water and steam powered drop hammers brought a stamping process to key making, superseded by the discovery of malleableising cast iron which came into use for casting key blanks from around 1816: these processes are reflected in the changing shape of key bows as mass production was introduced.

CHURCH LOCKS

Many

different types of locks can be found on church doors, depending on age,

location and patronage. They may be either rim locks, mortice locks or

even padlocks, and be of completely metal construction or of wood and

iron. The doors of many historic churches still carry an old wooden lock

although often you find that a modem 5-lever mortice lock has been installed

along side it to meet insurance requirements. Some of these old locks

will date from the foundation of the church and some from when the original

door was last replaced, but many are the result of a Victorian makeover.

|

|

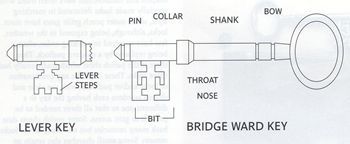

| Figure 3 A cast iron safe: this safe is typical of those produced in response to the George Rose Act of 1812 |

The generic name for the family of wooden locks is 'woodstock locks' a term dating back to the specialisation of trades springing from smithing, with some terms in common between the various branches. The earliest form is the 'Banbury lock' (Figure 1) in which the wooden stock is an integral part, with the metal components of the lock being mounted in the wood; the key is of a very distinctive form, with the collar being located within the width of the bit. Before industrialisation many Banbury locks were made by local craftsmen and so, especially amongst early ones, there are many variations to the standard deadbolt pattern, some having latchbolts in addition, operated by the key; some having double bolts and some double-handed for use in either a right-hand or left-hand application. There were also great differences, especially in the 18th century in the external shape of the keyhole, necessitating special keys, an additional security measure.

Improved iron working techniques in the 18th century were used in the 'plate lock', when all the working parts were mounted on a metal plate and the wood was merely a cover. Plate locks also had a long history of development, characterised by the shape of the metal plate which reflected the increasing degree of mechanisation in forming the corresponding recess in the stock. This progression from dovetail shape to rectangular, to rectangular with rounded corners, and to semi-circular end clearly illustrates the stages of development from hand made artefacts to the products of industrial processes via the ever increasing use of powered cutters. However, as the industry as a whole, with a few notable exceptions, was composed of small 'backyard factories' there was a considerable degree of overlap between all these various features which can make dating very difficult; for instance a modified version of the Banbury lock was made up to the end of the 19th century and even later. Woodstock locks were not left out of the proliferation of lock patents, there being several incorporating greater security, easier operation and different methods of manufacturing the various components.

|

|

| Figure 4 Plate lock from the 18th century showing hand cut stock and dovetail plate. |

One further development was fuelled by the Victorian passion for refurbishing churches and for things 'gothic'. This was the 'church door lock', a specific item which incorporated a latchbolt and ring handle as well as the deadbolt. As they were designed for use in this burgeoning market they are usually of much heavier and better quality, with varnished oak stocks and often highly decorated with chamfering and ornamental metal work. There was even a small market for imitation medieval locks, with a large and splendid stock covering a very ordinary standard lock mechanism. Woodstock locks seem to have been the preferred lock for church doors until the 20th century and the need to meet modern security requirements. However, iron case rim locks, especially the better quality ones from the latter half of the 19th century were sometimes used on new build churches and also mortice locks for those with a 'Modem' style or new doors.

Locks were not used solely on the main doors; there will usually be locks on bell towers, vestries and organ lofts too, often as old as the church, sometimes remaining forgotten during a modernisation. Ornamental wrought iron screens and gates enclosing private chapels and mausoleums were often fitted with specially made locks decorated in matching style, while outer porch grille gates have stout locks, although, being exposed to the weather, few have survived in working order, often being replaced by a modern padlock. Then there is the parish chest which traditionally had three locks. These could be any combination of locks and/ or padlocks, with the vicar and church wardens each having the key to a different one so that all three needed to be present to gain access. Some parish chests date back many centuries but not many of the locks remain. Some small churches also retain an ancient and crude alms or poor box, sometimes with provision for two locks, but these locks have rarely survived, having been superseded by modern padlocks or replaced by small 19th century and 20th century wall safe donation boxes. There are often small locks on aumbry doors (an aumbry is the small niche close to the altar in which the sacrament was kept), some of quite high security, and there is the ubiquitous cast iron safe installed in response to George Rose's Act of 1812 requiring church registers to be kept safely in an iron box. These safes are fitted with locks which have very complex warding (the gate through which the key passes when it is turned - see Figure 5), requiring skilfully made keys of the highest standard, carrying on the tradition of Georgian strongroom key.

|

|

| Figure 5 Late 18th/ early 19th century high security lock from a Butler's Pantry, dismantled to show complex warding and Barron's double tumblers. The keys are reproductions made to fit the lock. |

CONSERVATION, CARE AND MAINTENANCE

Locks

are very often forgotten in any conservation and maintenance programmes,

being regarded as totally utilitarian objects, while other aspects of

church architecture and decoration of a similar age are looked upon as

remarkable.

Because, upon the whole, very little is known of their history and development and there is very little published material to guide those interested, most people do not realise what exceptional artefacts are in their care. Because they are usually strongly made and can withstand an enormous degree of neglect no notice is taken of them until they cause trouble. It would perhaps be useful to include them in the 'quinquennial inspection', the essential survey of the fabric carried out every five years .

To ensure that problems are discovered in time, examine all the keys for signs of wear such as deep grooves on the nose of the key or on either side of the bit; these can lead to poor location of the key in the mechanism and difficulty in operation. Look at the keyholes, have they rusted or worn oval so that the key flops about, another cause of poor location. Remember always that a key and a lock work together and wear together, so when having a key duplicated if it is worn the result would be two worn keys! It is always better to make a key to the lock than to copy from a pattern key: locks can usually be fairly easily removed from doors, and, while the new key is being made, can be refurbished to bring them back to much easier and more efficient operation.

|

|

| Figure 6 Gate lock to 1868/9 South Transept memorial chapel in St Peter's Church, Deene, Northamptonshire, in the care of the Churches Conservation Trust. The design of this lock echoes the style of the decorative ironwork. It was refurbished by The Keyhole and three reproduction keys were made for it. |

Test the lock by locking with the door closed, if resistance is felt, try again with the door open. If the bolt extends freely, check the alignment of the bolt with the staple on the doorframe; the door may have dropped due to wear on the hinges or loosening of the wood joints and the bolt may be fouling the bottom of the staple. The closing of the door may have been affected by swelling of the wood in wet weather or damp conditions, again, causing the bolt to foul the staple; if only a minor or temporary degree of distortion is present, learning to exert firm pressure on the door whilst turning the key is usually sufficient to overcome the problem. Still with the door open, operate the lock so that the bolt is extended; if the bolt can be pulled further out until a sharp click is heard, this indicates wear to either the key or the lock mechanism or both and that the bolt is not seating correctly, which will eventually lead to a lockout situation; if the bolt can be moved freely to and fro, usually the spring is broken and as above could lead to a lock-out, but in addition this fault compromises the security of the lock. In both cases advice should be sought urgently.

|

|

| Figure

7 The effects of vandalism: a 19th century plate lock from St

Michael's Church, Cotham, Nottinghamshire, which is in the care of The Churches Conservation Trust. |

Conservation and care of locks is really simple matter once an inspection and maintenance programme is instituted and, mostly, is a matter of common sense. For example, a covered escutcheon on the outer face of a south or west facing door can do a lot to inhibit rusting of the mechanism of a lock by keeping out some of the prevailing weather. With woodstock locks check for signs of active woodworm, more common in later, cheaper quality beech stocks, especially if unvarnished, and treat with a proprietary solution. Discourage those who wish to oil locks or pack them with grease; oil and grease goes tacky with time, hampering the smooth working of the mechanism, and grit and dust which enters through the keyhole will stick to it, making a most efficient and wearing grinding paste. If oiling is felt to be absolutely necessary, use a graphite based product. Be aware and do not leave keys, especially attractive ones, easily available, there are light fingered people around. Above all, keep an eye on 'Fred'!

The front limb of a large key will often be bent slightly in towards the centre cut of the bit, being the piece which normally hits the ground first when the key is dropped; this should not be straightened unless absolutely necessary, as it is liable to fracture. Check that it is not cracked as well; if it is going to break off it usually does so inside the lock during operation, so if it is cracked at all, the key needs attention. Check that there are no shiny wear marks other than those on the nose of the key caused by operation of the mechanism, and also that the key still turns easily in the lock and there are no tight spots; all these symptoms indicate extra wear to the lock. If there are multiple keys to a lock, compare them: they will probably differ quite markedly in size and form, having been replaced or added to at various times and with differing degrees of expertise, ranging from the keys which originally came with the lock, to a competent locksmith, to the local hardware shop or blacksmith, to 'Fred the handy church warden' who just happened to have a key which with a bit of bodging would operate the lock. These varied keys will have been causing all sorts of problems to the lock over the years. Some will need to be discarded before they cause further damage but most can be brought to an average and the lock restored to good working order to accommodate them all. If the lock also has a latch mechanism, turn the handle or knob and note how far it has to turn before starting to retract the latch bolt; if it is more than a few degrees, then the latch mechanism must be worn.

| DO'S |

|

| DON'TS |

|

Recommended Reading

Books on locks are few and far between, and those available are mostly written with the collector in mind. The most readily obtainable is the small Shire Publications book, Keys, Their History and Collection by Eric Monk, which includes a useful bibliography. You might be able to borrow Locks and Keys Throughout the Ages by Vincent JM Eras, and An Encyclopaedia of Locks and Builders Hardware, produced by Josiah Parkes and Sons Limited, from your local library.

| The

Master Locksmiths Association can be found at: 5d Great Central Way, Woodford Halse, Daventry, Northamptonshire NN11 3PZ Tel 01327 262255 Fax 01327 262539 e-mail: mlahq@locksmiths.co.uk website: www.locksmiths.co.uk |