Masonry Cleaning: Nebulous Spray

Ian Constantinides and Lynne Humphries

|

|

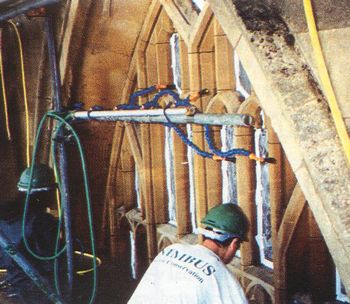

| Flexible heads directing a carefully controlled fine spray of water onto stone mullions (photograph by Nimbus Conservation Limited) | |

|

|

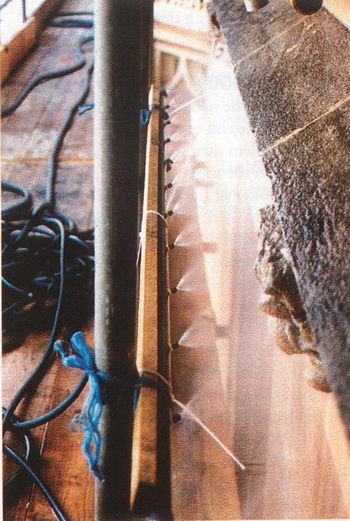

| Fixed heads creating a nebulous mist effect on flat areas of masonry (photograph by Paye Stonework & Restoration Ltd) |

Conservation is generally not a dramatic process. It is frequently imperceptible and by its very nature, usually subtle. Consequently, cleaning can be one of the most satisfying processes of conservation because its results are immediately visible, and it appeals to building owners since their investment is readily seen. However, focusing on the aesthetic benefits of cleaning does risk overlooking the cause of the soiling and ignoring the history of the building. Cleaning has become one of the most controversial aspects of conservation, raising fundamental questions. Is it always necessary or even beneficial? Are we too ready to clean? Many buildings have been damaged by cleaning in the past, and even the most appropriate cleaning techniques can be harmful. Arguably the most beneficial aspects of cleaning are to reveal the condition of the building where the dirt may have concealed cracks or structural faults and to slow down deterioration by removing damaging materials.

Of the various methods available, nebulous spray cleaning is among the gentlest. This article looks at some of the many factors to be considered before selecting this cleaning method as the most appropriate one, as well as giving a very general account of what it involves.

TYPES OF SOILING

Dirt or ‘soiling’ can simply be defined as material which is in the wrong place1. The question is how to remove this material without causing irreversible damage to the material which is in the right place, either directly or by introducing new material. To clean a building or material successfully we need to start by understanding the nature of the dirt.

Dirt or soiling may take many forms: airborne particles, gaseous pollutants and organic aerosols from industrial or vehicular emissions; biological soiling by algae, fungi, bacteria and lichen; non-biological soiling by iron staining, paint or graffiti, for example; and the list goes on. In turn, these may all be affected by water, temperature and wind, and by the effects of microclimate.

It may be that the soiling causes stone deterioration or decay, or reduces the permeability of the substrate; or it may simply appear as an unsightly surface discoloration. Over time architectural surfaces build up a patina that is due in part to airborne particles, weathering cycles and the mineralogy of the stone itself. Unlike surface dirt, the patina does not simply lie across the surface of the stone but is combined to varying depths within the masonry, be it stone, brick or terracotta. Although not necessarily damaging in itself, removing this layer detracts from the historic interest of the original and may expose a weaker substrate to decay. Another consequence of removing the build-up of patinas or encrustations is the potential mobilisation of minerals beneath the stone surface, leading to discolouration.

Consideration should also be given to potential re-soiling of the stone. Industrial emissions and environmental factors have changed since many of our buildings were last cleaned, and it is unlikely that re-soiling will take the same form.

SELECTING THE CLEANING METHOD

To select a cleaning method or even to assess the need for cleaning, it is important to survey the building first. The aim is to establish the types of material, their condition, the architectural style, previous treatments and the nature, cause and pattern of the soiling for each area. All these criteria must be considered in the context of the building itself, its history, construction, location and proximity to other buildings etc.

Next, cleaning trials should be carried out on inconspicuous areas, preferably using the operator who will be doing the work finally, as skill is just as important as method. The trial will help to:

- further ensure that the correct method or methods are selected

- determine how clean the surface can become (the ‘level of clean’) without risk to the fabric

- highlight potential problems.

Trial areas should be selected on their ability to illustrate as far as possible the range of soiling types and fabric conditions, to establish levels of clean which are not just desirable but also achievable, with the least risk.

Bear in mind that a uniform surface is rarely achieved without excessive and highly damaging masonry cleaning. An uneven patchy finish is more likely as buildings are subjected to a variety of weathering patterns: regularly rain-washed areas often appear brighter than protected areas, particularly on limestone buildings: and flat facades may also have uneven soiling due to apparently similar stones varying in porosity, pore size, capillary action, or surface texture. The art of cleaning, on aesthetic grounds, is to find the balance between the extremes. Often it is better to under-clean.

APPROACHES

There is a multitude of different cleaning methods, which may be wet or dry, chemical- or water-based, abrasive and nonabrasive, many of which have a place in conservation. There are positive and negative points to all methods and there is rarely a single method suitable for all situations. The least harmful method or combination of methods should be selected for each case.

NEBULOUS SPRAY OR INTERMITTENT MIST SPRAY

Low-pressure water washing is probably the least aggressive form of cleaning. Its application is particularly useful where water-soluble dirt is present or water-soluble chemical compounds bind the dirt. Thicker encrustations of soiling which tend to form in protected areas of a building not regularly washed by rain may be softened by the water and subsequently mechanically removed. However, it cannot be used to remove soiling or staining which is insoluble in water.

Nebulous spray, also known as intermittent mist spray, is a development of low-pressure water washing. The aim is to apply the minimum amount of water for the minimum duration to soften the dirt, thereby enabling its removal by scrubbing or other relatively gentle treatment. Ordinary low pressure water washing, by comparison, risks saturating the masonry, causing damage to the wall by mobilising salts and causing fixings to corrode for example, as well as damaging other features fixed to the wall such as internal plasterwork, timber or decorations. It can also lead to dry rot.

Only once all the investigations have been carried out, questions answered, options considered and the conclusion drawn that nebulous water spray cleaning fulfils all the criteria, should cleaning be commenced by those trained and skilled in the use of this cleaning method and following the guidelines established during trials.

GENERAL PROCESS

The system of nebulous sprays is based on the principle of passing water through a very fine mesh or filter to create a mist that is then passed through fine nozzles. The mist spray system can be set up with nozzles at intervals along the building, concentrating on areas of greater need and reducing the level where less dirt is present. The level of water may be controlled electronically or by timers, allowing pulse or intermittent spraying, to avoid ever having water running down the face of the building. Before starting, the porosity of the stone can be assessed in order to balance the amount of water and duration required.

As the system produces such a fine mist it is important to place the nozzles close to the building’s surface in order to ensure the water is directed correctly. Depending on the location and exposure of the elevation it is frequently necessary to erect a screen to reduce the risk of wind disturbance.

Nebulous spray systems can be designed to be incredibly flexible, directing the spray only where needed. Straight or flexible hoses may be employed depending on the requirements of the surface being treated and the nozzles from the hose may be grouped or spaced according to the severity of the dirt or encrustation being treated. Flat surfaces often require less water than a carved heavily soiled detail, which may require a cluster of nozzles positioned on an articulated hose to the profile of the carving.

ADVANTAGES

The most obvious advantages of cleaning with water are that water is cheap, readily available, safe and environmentally friendly. It is also particularly effective for cleaning limestone and marble.

The impact of the mist on the surface is negligible, reducing the risk of mechanical damage unless the surface is extremely friable. Consequently the risk of washing away weak pointing material or decaying stone is almost entirely eliminated.

Encrustations and dirt are softened progressively, reducing the risk of mechanical damage, and allowing greater control over removal and permitting more frequent monitoring of the surfaces. This ensures that the right levels of clean are achieved and reduces the risk of over cleaning. It also gives greater opportunity to re-evaluate the method or levels of cleaning than with many other cleaning methods.

Where the use of harsher methods of cleaning are unavoidable, prolonged use may be reduced by first cleaning with the nebulous spray system.

Removing softened material by brush between spraying cycles may accelerate the cleaning process and has the added advantage of enabling progress to be monitored.

A further advantage is the ability to control the quantity of water used. Excess run off, which this method avoids, is a particular problem with traditional water washing methods where weathered wash patterns formed by rainwater may channel the spray, avoiding adjacent areas of the masonry. As mist sprays use less water, a more even wash is achieved, avoiding the weathered wash channels and reducing the probability of saturation as the stone does not get so wet.

DISADVANTAGES AND RISKS

- Although the nebulous spray system reduces the risk of saturation enormously, this problem may still arise as a result of a failure in the timer, switch or in judging the porosity of the stone which can mean damage to internal finishes, hidden timber and ferrous fixings.

- Water cleaning methods may exacerbate deterioration when used on badly deteriorated masonry. The risk of water penetration through defective joints or fractures is still present with the nebulous spray system, illustrating the importance of carrying out a thorough survey externally, and continuous monitoring of the interior as cleaning progresses.

- As with all water treatments, the work should not be carried out when there is potential for frost damage.

- The network of hoses and bars situated close to the face of the building can restrict access and make monitoring or brushing down awkward.

- Efflorescence on the surface is possible where water treatments are carried out. Generally it is possible to estimate the risk of this prior to commencement.

- Water cleaning is less effective on siliceous stones such as granite and sandstone where the soiling is tightly bound to the silicate surface in insoluble compounds. Dirt on limestone is generally bound to relatively soluble chemical compounds.

- A frequent problem with many limestones and some sandstones is brown or orange staining caused by naturally occurring free iron within the stone being mobilised and carried to the surface. Consideration must also be given to the possibility of previous treatments, which may have been carried out, such as the application of a solution of copperas (ferrous sulphate) to Portland limestone in the 19th century in order to emulate the more fashionable Bathstone. Earlier conservation or cleaning treatments may also have a detrimental effect on the success of water cleaning.

- Finally the set-up and cleaning time required for the nebulous spray is greater than many other cleaning methods, however, this must be weighed against the increased control and gentleness of this type of spray.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN TECHNOLOGY

Time controllers can be programmed to open a valve for a set period, the length and frequency of spray being determined by the nature of the material being treated. Water flow meters are available to measure the quantity of delivered water and to calculate the output for sprays. The use of articulated pipe allows greater control over the location of the nozzles.

FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS

The employment of moisture switches, which react to differing levels of moisture in the stone, may negate the need to predetermine the porosity of the stone.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- C Andrew, Stone Cleaning: A Guide for Practitioners, Historic Scotland & The Robert Gordon University, Edinburgh, 1994

- Jonathan Ashley-Smith, Science for Conservators, Book 2 - Cleaning, Conservation Science Teaching Series, The Conservation Unit, 1983

- John Ashurst and Francis G Dimes, Conservation of Building and Decorative Stones, Butterworth-Heinemann, London, 1990

- Robert C Mack and A Grimmer, Assessing Cleaning and Water-Repellent Treatments for Historic Masonry Buildings, Preservation Briefs 1, HPS, National Park Service, Technical Preservation Services

- F Matero et al, 'An approach to the evaluation of cleaning methods for unglazed architectural terracotta in the USA', Architectural Ceramics: Their History, Manufacture and Conservation, A joint symposium of English Heritage and the United Kingdom Institute for Conservation, 22–25 September 1994, James & James, 1996

- RGM Webster, Stone Cleaning and the Nature, Soiling and Decay Mechanisms of Stone, Donhead, London, 1992