After the Games

Olympic Architectural Heritage

John Gold and Margaret Gold

|

||

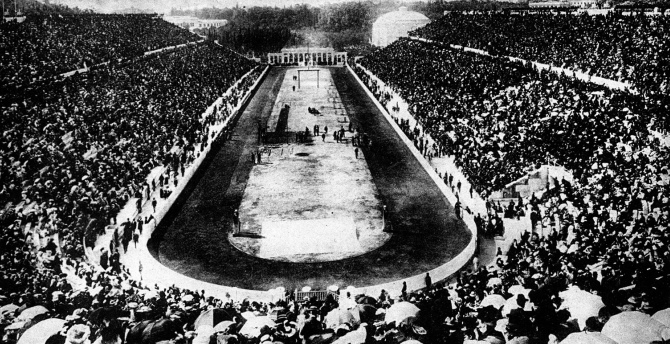

| The Panathenian Stadium, Athens during the 1896 Olympics |

There is a deep and abiding connection between the Olympics and their host cities. It started in the early 1890s when the nascent International Olympic Committee (IOC) decided that the modern Olympics would not follow the ancient pattern of having a permanent base, but would be an ambulatory event that was effectively franchised to the cities to which it was awarded. These ‘Olympic cities’, which in principle could be anywhere in the world, would supply the necessary sports venues and infrastructure in return for the right to stage the world’s most venerable games.

For the first few Olympiads, organisers made use of existing facilities or constructed temporary structures to house participants and stage the sports competitions. The Olympics, however, quickly grew. The participation of many more nations brought far larger numbers of athletes and officials, who were housed in sizeable ‘villages’. The addition of new events from sports as varied as cycling, gymnastics, shooting and equestrianism led to a festival of increased complexity and diversity that needed purpose-built facilities.

Given the glare of publicity that the Games attract, the organisers and their architects understandably tend to treat the occasion as an opportunity to create iconic structures designed to impress visitors and the world’s media – a strategy most recently illustrated at Beijing 2008 by buildings such as the ‘Water Cube’ Aquatics Centre, designed by a Chinese-Australian consortium and the ‘Bird’s Nest’ National Stadium, built by Herzog and de Meuron to a creative concept by Ai Weiwei. Frequently seen as lasting advertisements for technical prowess and creative design, such structures are permanent features of the cityscape and often become heritage sites of considerable significance. Yet because the Olympics imposes demands that are quite different from most other sporting events, it is inevitable that host cities struggle to find alternative uses for such venues after the Games leave town.

STADIA

Nowhere is this truer than for the main stadium. The IOC stipulates that there should be an open-air arena with around an 80,000 seat capacity that stages the opening and closing ceremonies and, in almost all cases, is also used for the athletics competitions. As the scene of many of the most memorable moments as well as being a prime focus for showpiece architecture, the Olympic stadium is emblematic of the Games.

There are few other occasions when these vast arenas are needed, however, and their shape and layout are poorly suited to the few mass spectator sports that might conceivably capitalise on their size. Football teams, for instance, complain about the lack of atmosphere, with the presence of the running track and the typically gentle rake of the seats of an athletics stadium making the action on the field feel distant for their spectators.

Without viable anchor tenants, their formidable maintenance costs cannot be borne without subsidy or by revenue from tourist visits and occasional concerts, often leading to them becoming labelled the ‘limping white elephants’ of the Olympic movement (Mangan, 2010). The experiences of three host cities – each with a distinct story to tell – point to the problems and challenges encountered with Olympic stadia and their legacy (Table 1).

| TABLE 1 DETAILS OF SELECTED OLYMPIC STADIA | |||

| CITY | YEAR | STADIUM DETAILS | POST-GAMES USE |

| ATHENS | 1896 | Panathenian Stadium built 4th century BC renovated 144AD excavated 1869/70 renovated for first ‘modern’ Olympic Games in 1896 |

music theatre celebrations and festivals heritage site archery and marathon events at 2004 Olympics |

| 2004 | Spyros Louis Stadium built in 1982 for European Athletics Championships renovated and roof added 2002-04 |

athletics cultural events football (Panathinakos FC/AEK Athens) |

|

| BERLIN | 1936 | built in 1913 for 1916 Olympics rebuilt for 1936 Olympics listed in 1966 renovated for 1974 World Cup reconfigured and roofed for 2006 World Cup |

mixed-use stadium athletics football (Hertha BSC) |

| LONDON | 1908 | White City Stadium built for 1908 Olympics as part of Franco-British White City Exhibition site at Shepherd’s Bush |

mixed-use stadium athletics football entertainment greyhound racing (core use 1926–1984) demolished 1985 |

| 1948 | Empire Stadium built for 1923 British Empire Exhibition and later renamed Wembley Stadium | national football stadium athletics cultural and sporting events demolished 2003 |

|

| 2012 | Olympic Stadium completed 2011 for 2012 Olympics | planned reconfiguration for dual use (football/ athletics) | |

ATHENS

The city of Athens has hosted two Summer Games, more than a century apart. For the first, in 1896, the organisers used the recently-excavated Panathenian stadium (or Panathinaiko) to house the athletics events and stage the major ceremonies. This had the advantages of making valuable links with the Games’ heritage and of successfully accommodating crowds of more than 50,000 at a modest cost – mainly incurred in renovating the seating and adding a modern running track.

Yet even then it was outmoded; its traditional elongated horseshoe shape with accentuated curves at each end hindered athletic performance and limited the nature of subsequent sporting uses. Such uses of the stadium, therefore, were largely retained for reasons of symbolic connection – most notably, hosting the archery competition and finish of the marathon races for the 2004 Summer Games. Nevertheless, it has become a valued feature of modern Athens. Standing with its open end facing on to Vasileos Konstantinou Avenue, one of the city’s main thoroughfares, its gleaming marble seating and memorial tablets to Olympic victors serve as a daily visual reminder of the ancient and contemporary significance of the Games for Greek society.

Rather less positive conclusions, however, might be reached about the Olympic stadium at Maroussi, a suburban district 9km north-east of the city centre, which was renovated for the 2004 Games. It originated as the Spyros Louis Stadium, a 75,000-seater venue built for the 1982 European Athletics Championships.

|

||

| The Olympic Stadium, Maroussi, Athens, 2009 |

Wanting an ‘architectural landmark of international recognition’, the organisers approached the Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava in March 2001 to submit a redesign for the stadium. The key element of the project involved installing double-tied tubular steel arches, rising to a height of 72m, which support a 25,000m² laminated glass roof. Although functionally designed to protect spectators from the heat by reflecting up to 90 per cent of the fierce sunlight, the additions also served to supply a high-tech image for the stadium.

The 2004 Games, however, were notorious for a lack of forethought about their legacy. For strategic reasons linked to Greece’s desire to be able to stage an Olympics at any time, the stadium will retain the capacity to host major athletics competitions. Nevertheless, other uses are sought to defray the costs. All three of Athens’ major football teams (Olympiacos, Panathinaikos and AEK Athens) have played there at different times. Panathinaikos and AEK Athens continue to do so, but neither is entirely satisfied with using a stadium designed for athletics, with the former seeking to build its own ground and the latter complaining about poor gates.

Between football fixtures, the stadium is used for around 15-20 rock concerts per year and receives a trickle of visitors, although there are no visitor facilities or tours. The stadium might represent iconic architecture designed to portray the new Greece but it sits unseen in an Olympic park, far removed from the major circulation patterns of the city, that is deserted at most times of day.

BERLIN

Heritage issues of a more awkward form arise in relation to Berlin’s Olympic stadium, which has never quite escaped its association with ‘Hitler’s Games’ (Hart-Davies, 1986). Located in a peripheral area to the west of the city, the 1936 stadium grew from a predecessor constructed in 1913 for the never-staged 1916 Olympiad. Werner March’s re-design of the 1913 stadium, originally designed by his father Otto, provided for a 110,000-seater stadium with a steel- and stone-clad structure that, in deference to Nazi ideology, was given a neo-classical facade with stone pillars and colonnades. Memorialised in Leni Riefenstahl’s film Olympia and immediately familiar from television documentaries about Nazi Germany, the Olympic stadium lay at the heart of the Reichssportfeld – once the world’s largest sports complex (below left).

It became a focus of attention throughout Germany in the period leading up to and including the 1936 Games for a regime that appreciated and mobilised the opportunity for powerful spectacle. After the Games, the city and state gained the infrastructural legacy of a sports complex and parade ground that could be used for military purposes and for future National Socialist celebrations.

|

||

| Aerial view of the Reichssportfeld, Berlin, 1936, with Olympic Stadium top right |

Little damaged by the war, use of the stadium after 1945 was controlled by the occupying forces. A short phase of opening the grounds ended when the British Army requisitioned the Reichssportfeld. It then remained closed to the public until transferred to the city council (Magistrat) of Greater Berlin in June 1949. After languishing for some years, it was adopted as the home ground for Hertha Berlin Football Club and was listed for preservation as a historic structure in 1966.

While externally little changed, the stadium was renovated internally by the addition of spectator covering for the 1974 World Cup, with a partial roof designed by Friedrich Wilhelm Krahe. Complaints from international sports bodies and others about the stadium’s dilapidated facilities and ailing structural condition led to a debate that included the possibility of demolition.

Its saviour was again a sporting mega-event. In 1998, Germany’s gained the nomination for the 2006 World Cup, with the Olympic Stadium in Berlin accepted as its key venue. After appraisals and an architectural competition, the Hamburg-based architectural practice gmp (Architekten von Gerkan, Marg und Partner) won the contract to renovate the stadium at a cost of €242 million (Meyer, 2010). Only perhaps at this stage could the long-term future of the Olympiastadion be guaranteed.

LONDON

The first of London’s three Olympic stadia was less fortunate in this regard. The main venue for the 1908 Games was the White City, the first purpose-built Olympic stadium and also the largest sports venue of its day. Its enormous concrete bowl, designed by George Wimpey, enclosed athletics and cycle tracks, a 100m swimming pool, platforms for wrestling and gymnastics and even archery. Called the White City after the gleaming white stucco rendering applied to the Franco-British Exhibition buildings (to which the Olympics were attached), its foundation stone was laid on 2 August 1907 and the stadium was inaugurated on the opening day of the adjoining exhibition (14 May 1908). It held 93,000 spectators, with 63,000 seated.

|

||

| The White City Stadium, West London, 1908 |

Although the Games themselves were regarded as successful, they left the less desirable physical legacy of a huge and largely unwanted stadium. Retained after 1908 despite an initial decision to demolish it, the White City was scarcely used for two decades before passing to the Greyhound Racing Association in 1926. It was then renovated, with its capacity reduced from 93,000 to 80,000, the cycle track removed and a greyhound track installed over the existing running track. In 1932, the reconfiguration of a running track to a new 440-yard circuit allowed the stadium’s use for national and international athletics events.

On occasions, the White City did stage large-scale sporting festivals, such as the 1934 British Empire Games and the 1935 International Games for the Deaf, and provided a base for British athletics from 1933 onwards. However, when the athletics events moved to their new home at Crystal Palace in 1971, the stadium deteriorated. It continued to host greyhound racing until 1984 but became an increasingly forlorn structure that few mourned once it was demolished in 1985 to make way for offices for the British Broadcasting Corporation and housing.

Little needs to be said about the city’s second Olympic stadium at Wembley, which was rarely regarded in the public mind as an Olympic Stadium. Held against a background of extreme austerity, the 1948 Games saw the organisers make full use of whatever was available. With custom-built stadia out of the question, they designated the Empire Stadium at Wembley, originally built for the 1924 British Empire Exhibition, as the Olympic stadium even though it had not staged an athletics competition for more than 20 years.

Once the 1948 Games were over, the stadium returned to its use as a greyhound racing venue (1927-1998), but more importantly as the national football stadium staging major domestic and international matches, as well as providing ideal facilities for pioneering outdoor arena rock concerts in the 1970s. It was demolished in 2002-3 and replaced by a purpose-built football stadium designed by Foster and Partners and HOK Sport. The lengthy delay before it could open in March 2007 was due more to indecision about its purpose than constructional problems, with attempts to combine athletics and football in a single stadium eventually scrapped in favour of a dedicated football stadium.

|

||

| The Olympic Stadium, London, June 2011 |

For the 2012 Olympic Games, London promised a utilitarian purpose-built athletics stadium (left) which after the Games would become a multi-purpose venue that included athletics at its core. Designed by Populous (formerly HOK Sport), the 2012 stadium addressed the ‘white elephant’ problem by combining a core structure that could find permanent usage with a temporary steel-and-concrete top tier for 55,000 spectators that would be removed after the Games. This would downsize the stadium to 25,000 seats, with the top tier, as originally hoped, possibly reused in a stadium elsewhere.

The visual impact of the stadium was to be provided by a fabric wrap which would be draped around the stadium. This fell victim to spending cuts at the end of 2010, but was reinstated after it seemed likely that the cost could be borne by sponsorship. Understandably, the success of this approach to stadium design rests on finding an anchor tenant that would allow the stadium to be used profitably while still permitting occasional athletics meetings. At the time of writing [December, 2011], however, the decision to retain the stadium in public hands as a mixed-use venue without having first found such a tenant means that, despite all endeavours, yet another main Olympic stadium seems destined to join its immediate predecessors as a white elephant.*

CONCLUSION

The stadia discussed here show in microcosm the challenges faced by all Olympic cities as they reconcile the demands of the Olympic movement, the desire to house the Games in a memorable fashion and the provision of a viable post-Games future for the facilities delivered. London has tried to pre-empt these future problems for its Olympic sites by engaging in the most comprehensive exercise in legacy planning yet attempted. However, the vagaries of post-Games market conditions will impact on these plans in ways that could well call into question the architectural heritage that will result from these Games.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- D Hart Davis, Hitler’s Games: The 1936 Olympics, Century, London, 1986

- JA Mangan, ‘Prologue: guarantees of global goodwill: post-Olympic legacies – too many limping white elephants’, International Journal of the History of Sport, 25, 2010

- M Meyer, ‘Berlin 1936’, in JR Gold and MM Gold (eds), Olympic Cities: City Agendas, Planning, and the World’s Games, 1896-2016, 2nd edition, Routledge, London, 2011

* Editor's note: as of July 2012, the deadline for the submission of tenancy bids for the Olympic Stadium had been extended and it now seems unlikely that the stadium's future will be decided before October 2012. For the latest information, see the website of the London Legacy Development Corporation.