Pond Plants and Wildlife

Mark Woods

|

|

| A typical stone-lined 19th-century ornamental garden pool: regular silt clearance for the fish limits the diversity of species that the pond can support. |

In 1999 the Pond Conservation Trust estimated that there were approximately 400,000 ponds in Britain.(1) Ponds are important not only as a unique resource for biodiversity, an amenity for a wide range of interests, and a visual focus in many landscapes, but also because they form a key part of the culture and history of Britain. An estimated 98 per cent of the ponds in lowland Britain are of artificial origin and were created for a wide range of agricultural, industrial and ornamental purposes.

Some of Britain’s oldest artificial ponds are associated with medieval manors and monasteries, and were created for functional rather than ornamental reasons. During the 18th century, many of the surviving manor ponds were modified for aesthetic reasons and incorporated into the gardens of large country houses or enlarged into lakes and surrounded by parklands.(2) Others were modified for water storage, often to supply fountains and artificial waterfalls. Some were stone-lined, stocked with ornamental plants and sometimes fish, and regularly cleared of silt and debris. As a consequence, they are usually of limited value for nature conservation, although they remain of enormous cultural and historic significance. However, many former manor and monastic ponds were located in less formal areas of estate gardens such as ornamental woodlands and grazed lawns. It is these ponds that have often developed a significant nature conservation interest because of their age, continuity of low-intensity management and lack of agro-chemical inputs.

In the late Victorian and Edwardian periods, ponds and pools were created for many different ornamental and leisure purposes in public parks and private gardens. The variety is almost endless, from rambling picturesque boating ponds and shallow skating ponds in public parks, to small duck ponds on village greens, and from the stiff canal-like pools popularised by Gertrude Jekyl, to romantic Japanese water gardens. In each case, complex ecosystems may have to be taken into account whenever conservation and repair work is being considered.

LOST PONDS

While the cultural significance of ponds in historic parks and gardens is often obvious, their ecological value has only recently been fully appreciated. One reason for this is that, when compared with larger water-bodies or rivers, ponds in the countryside are relatively ephemeral features, and without intervention they silt up, often disappearing in less than a century. Agricultural ‘improvements’ and, to a lesser extent, urban development in the wider countryside have also led to significant losses in the past century(1) (perhaps as high as 75 per cent) and a general decline in biodiversity. However, the loss of ponds in historic landscapes has been much less severe because of protection and sympathetic management.

|

||

| Water-lilies are a familiar site in ponds, lakes, canals and slow-flowing rivers, but most populations of white water lily Nymphaea alba in Britain are not native. Stands of any water-lily species in a pond can provide excellent habitat for pond fauna including great crested newts. However, the ecological value of a pond will decline if the majority or the entire pond surface is covered by water-lily pads. This is because the heavy shade will suppress the growth of other plant species. In addition, dense stands of water-lily can reduce the area available for male newts to display and attract females. Therefore, management of aquatic plants is usually essential to maintain the long-term ecological interest of a pond. (Photo: Helen Evriviades, BSG) | ||

|

||

| The pond above is located in the grounds of Walton Manor, a 16th century building at Milton Keynes. It is a plastic-lined pond set within a formal landscape of paving, mown lawns and ornamental shrubbery that is approximately 4m in diameter and 0.75m in depth. This pond contains medium-size populations of great crested newt (peak count of 29 adults) and smooth newt (peak count of 45 adults) and common frog has also been recorded; most importantly the pond does not contain any fish species. The newts lay their eggs on the water-lily (genus Nymphaea) pads and strands of filamentous algae. (Photo: Natalie White, BSG) |

||

|

||

| The photograph above shows a pond in the latter stages of natural succession at Cotswold Wildlife Park, a process whereby standing water-bodies gradually infill with silt and debris, and change to wetland, then ultimately to terrestrial habitat. The pond shown is now dominated by bottle sedge Carex rostrata in the centre, with hard rush Juncus inflexus and marsh bedstraw Galium palustre on the margins, and could be classified as a wetland rather than aquatic habitat. Although ponds such as this can support amphibians, they are sub-optimal for breeding purposes, because of a lack of open water for display. Unless there is good reason, ponds with a complete cover of wetland rather than aquatic plant species should not be restored by removal of vegetation and silts because wetlands are often as valuable as ponds and will support a different biological community to that which is typically associated with ponds. In all cases, a survey should be carried out before any management is implemented. (Photo: Helen Evriviades, BSG) |

National pond surveys carried out in 1996(3) and targeted research have highlighted the importance of ponds for biodiversity. For example, Wright et al (1996)(4) demonstrated that invertebrate diversity and abundance were greater in ponds than in rivers. As a result, ponds are now included in the updated list of the UK government’s Biodiversity Action Plan, ‘Priority Habitats’.(5) Its website lists more than 50 priority species that are associated with ponds for conservation action, either because of significant declines in recent times, or because they are rare and threatened by extinction. Ponds are also used for breeding by all three European protected(6) amphibians that occur in Britain including the great crested newt Triturus cristatus, the pool frog Rana lessonae and the natterjack toad Bufo calamita.

WHAT MAKES A GOOD POND FOR WILDLIFE

It is difficult to be specific about what defines a ‘good’ pond for wildlife because different types of ponds will support characteristic flora and fauna dependent on their origin and local environmental factors such as substrate, watersource and surrounding habitat. However, there are general features that, if present, are likely to encourage ecological interest.

Water quality is important. Ponds with a high ecological interest are usually associated with water that is free of pollutants and has low levels of soil nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphate and potassium. High nutrient loads in ponds have become increasingly problematic in the British lowlands, largely as a result of agricultural intensification. This can encourage algal blooms which have a severe impact on both biodiversity and the ornamental value of a pond.

An isolated pond is usually of less ecological value than one that is located in a cluster of others, because the risk of species extinction increases as pond density declines.(1) Recolonisation of ponds that have lost populations of species becomes less likely with increasing isolation, because the more uncommon species associated with ponds often have poor dispersal mechanisms.

Ponds with structural variation are more likely to provide opportunities for a higher number of species than ponds with a more uniform structure. For example, small variations of pond-bed topography allow a greater number of dragonfly species to co-exist with each other. In a more uniform environment, smaller less-competitive dragonfly species will be less able to hide and avoid predation by the larger dragonfly species.

Native plants are preferable to ornamental ones because they support a greater diversity of animal species, but in an ornamental setting, native plants may not be appropriate. In this situation, some degree of invasion by native species should be tolerated as these plants can be helpful to wildlife: even the most heavily managed ponds can support wildflowers in the margins and the submerged plant community will usually contain some native species.

To some extent, a lack of native species in a garden environment can be offset by complex plant architecture. In general, the more diverse the plant structure, the greater the range of opportunities that organisms can exploit. In the case of a pond this can mean that a diverse range of emergent, floating-leaved and submerged aquatic plants is best.

It is important to remember that too much pond vegetation can have a detrimental impact and can cause undesirable chemical changes such as daily oxygen depletion. Ideally, a pond with approximately 35 per cent open water and 65 per cent vegetation cover during late summer is recommended, as some species require areas that are relatively plant-free. Newts, for example, need areas of open water to mate.

Broadleaved trees and shrubs on the margins of ponds can be both desirable and detrimental. Many aquatic invertebrates feed on decaying organic matter and the input of small amounts of deadwood and leaves from bank-side trees is desirable. In addition, trees on the north side of a pond can be beneficial because they shelter the pond surface and keep areas ice-free, allowing wildfowl such as diving ducks to forage. However, too many bank-side trees will shade the surface of the pond and restrict aquatic plant growth and excessive input of dead leaves can rapidly increase water acidity and accelerate the rate of infill.

PONDS IN HISTORIC LANDSCAPES

In historic landscapes, estate managers will often be expected to manage ponds primarily for their ornamental appeal, but this does not need to conflict with ecological management. For example, many of the techniques employed to maintain the aesthetic appeal of ponds, such as clearance of emergent vegetation, can also benefit wildlife.

In a short article it is not possible to cover all aspects of pond management techniques, but the Brackenhurst case study which follows covers many of the generic issues and solutions for restoring and managing a pond of significant ecological, historical and cultural importance.

|

|

Above: Brackenhurst Hall and dew pond in the early 1930s and, below: The rose-garden pond at Brackenhurst Hall in the 1930s (both photos: Nottingham Trent University Archives) |

|

|

|

| Main picture: The dew pond at Brackenhurst Hall, which was constructed in 1928, is a fine example of a pond with significant ecological and historical value in a formal garden setting. (Photo: Neville Davey) | |

BRACKENHURST HALL DEW POND

The 200ha Brackenhurst Estate is approximately 1.5 miles to the south of Southwell in Nottinghamshire. The estate includes the 18th century, Grade II-listed Brackenhurst Hall, gardens and parkland. The hall and its grounds have been used as an agricultural college for over 60 years and in 1999 merged with Nottingham Trent University. The hall is now home to the university’s School of Animal, Rural and Environmental Sciences, and its gardens are managed by the university’s estates department and horticulture staff at the Brackenhurst campus.

In 1928 the gardens were landscaped in the style of Sir Edwin Lutyens, including an Italianate courtyard, a sunken Dutch garden, rose garden, Japanese rock garden and a teardrop-shaped dew pond that was partly set in ornamental woodland, with a boathouse and ‘willow pattern’ bridge. Water collected from the roof of the hall was fed through a drainage system to supply water to the dew pond and small stone-lined ponds located in the formal garden areas. Excess water drained out of the system via outflow pipes into the ha-ha that still surrounds the gardens.

|

|

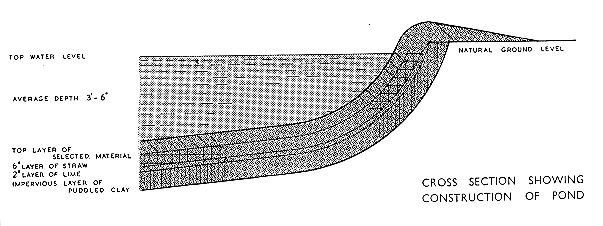

| Cross-section of a typical dew pond. The straw and lime layers are flexible and protect the impermeable layer of puddled clay from damage by grazing livestock. (Source unknown) |

The dew pond was of particular historical interest because of its traditional design and construction, a feature not commonly found in Nottinghamshire. Although the dew pond was primarily designed as an attractive feature, its close proximity to the hall ensured a useful source of water in the event of a fire.

Prior to its merger with Nottingham Trent University, a lack of resources during the latter half of the 20th century led to some of the garden features falling into a state of neglect. Fortunately, the development of horticultural courses on the campus provided the expertise and labour to start to restore the gardens. Discussions with English Heritage during the late 1990s identified the dew pond and its associated features as a high priority for restoration and work began in March 2001. By this time the dew pond was usually dry in summer, choked with tall reeds and partly infilled at the east end, which had isolated the boathouse from the pond. However, the restoration was not straightforward because, a year before the work was due to start, biological surveys identified the presence of great crested newts in the gardens.

|

|

| A great crested newt, captured during post-restoration monitoring of the Brackenhurst dew pond. The distinctive belly patterns can be used to identify and track individuals during future monitoring events. (Photo: Neville Davey) |

The presence of the newts required the restoration work to be carried out under a conservation licence from English Nature (now Natural England). In order to obtain a licence it was necessary to demonstrate that the work would be of benefit to the newts. Clearly the provision of a restored 150m2 breeding pond would be a conservation gain for newts, but horticultural staff raised concerns about the constraints of managing the gardens, given the presence of a protected species.

Concerns were addressed by the preparation of an action plan which minimised the risk of harming newts and enabled the gardens to be managed without undue constraints. Although many ponds will not contain newts or protected species, this example confirms the importance of carrying out biological surveys and historical research before restoring a pond or resuming pond management in historical landscapes.

The restoration work required tracked excavators to remove vegetation and soils, and to restore the original profile. The damaged dew pond lining was removed and replaced by a butyl liner and the water control structures were repaired. All of the work was supervised by a licensed ecologist (a requirement of the English Nature licence) and any animals encountered (including the newts) were trapped and removed to suitable habitat elsewhere in the gardens.

Photographs taken in the early 1930s clearly showed that the pond margins were planted with emergent reeds and tall herbs, and that the open water areas contained small patches of water-lily (genus Nymphaea) but it was not possible to identify the actual plant species. If the pond had been located in the parkland areas, then native or naturalised species would have been selected for planting. However, given the pond’s location in the gardens, a mix of native and ornamental species was considered to be more appropriate.

In order to balance the requirements of wildlife with amenity considerations, the marginal strip of emergent vegetation around the dew pond is restricted to a width of less than 1.5m and submerged and floating leaved plants do not occupy more than 65 per cent of the open water areas. Routine vegetation control is carried out by hand-raking and pulling during winter, when newts are absent. The work is labour-intensive and often unpleasant, but if regularly undertaken will be less intrusive than occasional large-scale interventions. After removal, plant materials are left next to the pond for two to three days to allow stranded invertebrates to return to the pond.

|

|

| The rose-garden pond supports a small breeding population of great crested newts. The pond is leaking (hence the low

water levels), but is due for restoration as part of a larger project to restore the rose-garden. The stripped and weighted plastic

bags provide newts with alternative egg-laying substrate and will be replaced with suitable plants once restoration work is completed. A brick ramp is installed in the pond during summer to allow young amphibians to escape. (Photo: Neville Davey) |

Parkland ponds are often effectively managed by controlled livestock grazing and trampling. The action of livestock at the water’s edge fragments marginal vegetation and creates muddy areas. Wet patches of mud create opportunities for specialist invertebrates and short annual plants, which would not occur in the absence of livestock. However, some control of livestock is essential to prevent too much damage to ponds. For example, exclusion of livestock during early summer will protect amphibians during their breeding season.

If vegetation control is necessary, mechanical and chemical controls should be avoided unless there is no other satisfactory alternative. However, there are cases where chemical control may be necessary to control the spread of plant species listed on Schedule 9 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. A significant number of these species are aquatic (see text box below) and pond managers should avoid planting these species in historic landscapes.

Many ponds in historical landscapes will contain populations of fish. These ponds are often devoid of amphibian populations because of predation of larvae and at high densities of fish the diversity of invertebrates can also be affected. However, this is not always the case and for ponds already containing fish there is little ecological value in removal unless the pond is overstocked. However, if protected amphibians such as great crested newts are present, then the introduction of fish is a criminal offence under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and ignorance of the presence of the newts is not a defence; it is the landowner’s duty to find out!

When the dew pond was restored, the mature bank-side trees were retained. The south and the north banks have been kept clear of trees to maintain views from the hall and to minimise shading of open water. Elsewhere, the bank-side trees have been regularly pruned to maintain their shape and keep them in a safe condition, but small amounts of deadwood (twigs and shoots) are allowed to fall into the pond to provide food for the many aquatic invertebrates that feed on decaying organic materials.

Water control structures such as silt-traps are regularly checked to ensure that they are still functional. To date, repairs have not been required, but if necessary they will have to be carried out under the supervision of a licensed ecologist because the newts use these structures for resting and foraging.

SCHEDULE 9 OF THE WILDLIFE & COUNTRYSIDE ACT 1981 |

|

It is an offence without a licence, to plant or cause to grow, any plant listed on Schedule 9. The list includes plants that may pose a threat to our native flora. The list is revised from time to time and the current list of aquatic species is provided below. |

|

Water fern Azolla filiculoides |

Floating pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides |

Canadian pondweed Elodea canadensis |

Duck potato Sagittaria latifolia |

Fanwort Cabomba caroliniana |

Curly waterweed Lagarosiphon major |

Parrot’s-feather Myriophyllum aquaticum |

Water primrose Ludwigia grandiflora |

Australian stonecrop Crassula helmsii |

Water lettuce Pistia stratoites |

Giant rhubarb Gunnera tinctoria |

Floating water primrose Ludwigia peploides |

Water hyacinth Eichhornia crassipes |

Nuttall’s Pondweed Elodea nuttallii |

| Himalayan balsam Impatiens balsamifera |

Water primrose Ludwigia uruguayensis |

The small stone-lined ponds in the gardens continue to support breeding amphibians, so any work such as masonry repairs, vegetation clearance and cleaning are carried out during winter. During the amphibian breeding season brick ramps are temporarily placed into two of the stone-lined garden ponds that have vertical sides. The ramps allow young amphibians to leave the ponds and are subsequently removed towards the end of summer when young amphibians have left the pond.

Management of the surrounding gardens has been adapted to reduce the risk of harm to newts. Structural repairs and maintenance are carried out during spring and early summer when newts are in the breeding ponds. The grasslands surrounding the pond are kept short throughout the year to deter newts from using this habitat for dispersal. Flowerbeds next to the pond are planted with perennial plants and mulched with wood chips to minimise the need for soil cultivation and to reduce the risk of disturbance to newts. The gardens are managed organically, so the risk of water pollution and amphibian poisoning has been removed.

With careful timing and appropriate techniques, the aesthetic and ecological value of Brackenhurst’s dew pond has been restored. The dew pond is once again an attractive and key feature of the gardens. The ecological value of the gardens (including the dew pond) has been recognised by its designation as a County Wildlife Site and the population of the newts, now estimated to be greater than 2,000 adults, is considered to be of regional importance. The pond also supports a diverse range of plants, nesting wildfowl, foraging bats, and at least eight dragonfly and damselfly species.

|

|

| The boathouse and willow-pattern bridge at the east end of the dew pond three years after restoration. Marginal vegetation has developed further, but the channel is being annually cleared of floating and submerged vegetation to provide male great crested newts with sufficient open water to display to females during courtship. (Photo: Neville Davey) |

Notes

1 P Williams et al, The Pond Book: A Guide

to the Management and Creation of Ponds,

Pond Conservation Trust, Oxford, 1999

2 E Agate and A Brooks, Waterways

and Wetlands: A Practical Handbook,

BTCV, Reading, 1997

3 P Williams et al, Lowland Pond Survey

1996, DoETR, London, 1998

4 JF Wright et al, ‘Macro-invertebrate

Frequency data for the RIVPACS III

sites in Great Britain and their

use for conservation evaluation’,

Aquatic Conservation: Marine and

Freshwater Ecosystems, 6, 1996

5 The UK list of priority habitats can

be viewed online at www.ukbap.org.uk/PriorityHabitats.aspx

6 The Conservation (Natural Habitats &c)

Regulations, HMSO, London, 1994

Useful Contacts

County Wildlife Trusts – you can find your county trust by searching The Wildlife Trust’s website: www.wildlifetrusts.org

The Pond Conservation Trust: see www.pondconservation.org.uk

County Biological Records Centres – you can find species records for your local area by searching the local records centre pages on the website of the National Federation for Biological Recording: www.nbn-nfbr.org.uk

Contemporary photographs were provided by Neville Davey CBiol MSB CEnv MIEEM (lecturer, Nottingham Trent University) and archive photographs were kindly supplied by Nottingham Trent University.