Saving a Century

Ian Dungavell

|

| The Euston Arch, demolished in 1962, was a powerful symbol of the railway age and a victim of the motorway age. (Photo: Herbert Felton 1960, English Heritage, National Monuments Record). |

|

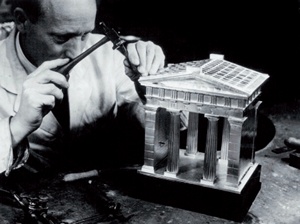

| A silver model of the Euston Arch made by Carrington & Co bearing the inscription: ‘to perpetuate the memory of one of London’s finest historic monuments’ was presented to the Victorian Society by Frank Valori, the demolition contractor, in 1962. It was later stolen. |

The Victorian Society, which celebrates its 50th birthday this year, held its first meeting on 25 February 1958 at 18 Stafford Terrace, Kensington, now the Linley Sambourne House museum. The catalyst was Anne, Countess of Rosse, whose husband was chairman of the Georgian Group, and the new society drew its strength from the already-developing interest in Victorian architecture in the circles of the Architectural Review, Country Life, and the Victoria & Albert Museum. It was not, as Mark Girouard has pointed out, a few lone voices crying in the wilderness, but a banner under which many people from different backgrounds could assemble.

Lady Rosse brought glamour as well as a stamp of social approval to a group which included architects such as Hugh Casson and Harry Goodhart-Rendel, academics such as Nikolaus Pevsner, journalists such as Christopher Hussey and Mark Girouard, and popular figures such as John Betjeman. Lord Esher was the first chairman.

The society was, from the start, interested in Edwardian architecture too, although ‘The Victorian and Edwardian Society’ was no doubt considered too much of a mouthful. Its period of concern is from 1837, the year Victoria came to the throne, to 1914, the year the First World War broke out. Our sister society, the Twentieth Century Society (born in 1979), is concerned with the period from 1914 onwards.

From its inception, the society was very careful not to attempt to defend everything Victorian. It acknowledged that ‘many Victorian buildings are unsuited to modern conditions or on sites needed for redevelopment; many are downright second-rate or have a merely sentimental charm. Others are of such quality that almost no argument would justify their destruction.’ But now, with considerably more experience about how old buildings might be adapted for new uses, a much greater understanding about how historic buildings are valued by their communities, and a much less sanguine attitude towards new developments, we do stick our neck out for a wider range of Victorian buildings.

The first great campaign was for the Euston Arch (1836-7 by Philip Hardwick), not an arch at all, of course, so much as a gigantic Doric gateway. Plans to rebuild Euston Station, on the cards since the 1930s, finally brought it down in 1962. It was a victim not of necessity but of the desire of British Railways’ management for a totally modern image for the railways. The Architectural Review dubbed it the ‘Euston Murder’. Our suggestion that the arch and lodges be moved closer to Euston Road was deemed impossible, even though, as you can see today, there was plenty of room for them to be re-erected in front.

The Treasury estimated that the move would cost about £190,000 but, given the general unwillingness to retain the arch, we can be pretty certain that the figure was not an underestimate. Moreover, it was, as we sadly noted, ‘rather less than the Treasury ungrudgingly paid out about the same time for the purchase of two rather indifferent Renoirs, which no one was threatening to destroy’.

There was also pressure to get the building down quickly, and to make sure it stayed down. Despite demolition having begun in December 1961, plans for the new station were only completed in 1963 and then rejected by the London County Council the same year. The demolition contractor, Frank Valori, had been prevented from numbering the stones to allow possible re-erection, even though he had an undoubted affection for the building. He presented the Victorian Society with a silver model of the arch, made by Carrington & Co, bearing the inscription: ‘to perpetuate the memory of one of London’s finest historic monuments'. The model has since been stolen, but there is a similar one in the National Railway Museum at York.

At the time, it was argued that the new Euston Station would be a worthy replacement, but the train sheds are a crushing disappointment. The concourse building may have a certain elegance, as do the Seifert office blocks in front, but the station is now up for redevelopment in its turn, and one wonders whether all this justified the loss of buildings which had much more enduring qualities.

|

|

| The Coal Exchange, London, photographed just before demolition in 1962 (Photo: Planet News Ltd) |

Mr Valori was certainly being kept busy by the desire for a modern Britain; the early 1960s were a difficult time to be a demolition contractor with an architectural sensibility. Next up was the Coal Exchange on Lower Thames Street in the City of London, built in 1847-9 to the designs of James Bunning, the City architect. And, once again, the Victorian Society had perfectly sensible suggestions as to how it might be saved.

The interior was particularly important: it was one of the earliest and most remarkable examples of cast-iron construction in the world, several years before the Crystal Palace, and comparable in date with Labrouste’s libraries in Paris. There were three storeys of richly-ornamented cast-iron galleries in an extraordinary domed rotunda, decorated with images illustrating coal’s geological, social and economic significance. And, being made of cast-iron, it was eminently suited to dismantling and re-erection elsewhere. Some thought that it might be incorporated as part of the Barbican redevelopment, or a section preserved in a museum such as the Victoria & Albert. An enquiry came in from the museums director of Durham County Council, and there was even a possibility of using the rotunda as the centrepiece of the new National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne.

Dismantling and storage would have cost £20,000 and the City of London gave the Victorian Society three and a half weeks to raise the sum. But even if demolition had been necessary, and today we would be far more hesitant to lose a building of such quality, why the rush? Even at the time it was acknowledged that the road widening for which the Coal Exchange was condemned could not start until 1972 at the earliest, and in the end the site was still empty in 1980. The building had come down in 1962.

The face of modern Britain was being reshaped, and many people felt that Victorian buildings were like a toothless old aunt. At the same time, the need to cope with increasing volumes of traffic provided the perfect excuse to get rid of embarrassing and often slightly tatty reminders of Victorian self-confidence. Such it was with the re-planning of Whitehall, which gathered additional impetus from the need to house growing numbers of civil servants in better conditions.

|

|

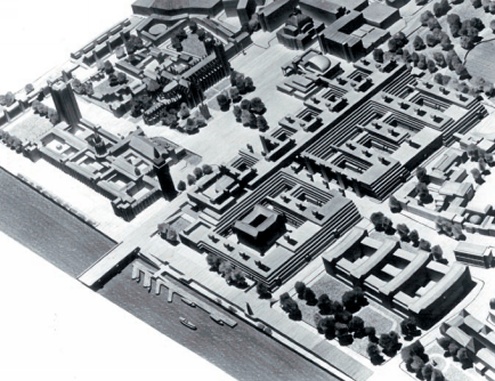

| Model of Sir Leslie Martin’s proposal for the redevelopment of Whitehall. Gone are most of the Victorian and Edwardian buildings (except Norman Shaw’s New Scotland Yard, crammed in a courtyard). Inigo Jones’s Banqueting House survives as a traffic island. |

In 1964 Sir Leslie Martin was appointed by the government to oversee the comprehensive re-planning of Whitehall. The greatest casualty was to be the Foreign Office by Sir George Gilbert Scott (1863-8), whose fate had already been announced the previous year by Geoffrey Rippon, Minister of Public Buildings and Works: ‘I have... decided to demolish the existing building’. By this time it was overcrowded and in need of refurbishment: his successor described it in 1965 as ‘a squalid office slum, incapable of treatment to bring it up to the standards and working conditions which are reasonably expected nowadays’.

Once again, the Victorian Society proved willing to compromise. Indeed, by today’s standards, it was perhaps too willing. But things really were very different back then when we had to campaign for buildings the loss of which today would be almost unthinkable. The society drew up a plan identifying ‘buildings to be preserved at all costs’, ‘buildings of secondary importance, demolition of which should be avoided if possible’ and ‘buildings not worthy of preservation’. Astonishingly, in the last category came such great buildings as William Young’s War Office (1898-1906) and John Brydon’s Government Offices on Great George Street (1898-1915).

The society wrote that: ‘at least seven-eighths of the Whitehall area remains suitable for clearance. The Victorian Society is quite as keen that bad Victorian and Edwardian buildings should be replaced by something better as it is that good Victorian and Edwardian buildings should be protected’. Values change and, as we refine our appreciation, what was considered ‘bad’ then may be judged differently today.

|

|

| The Downing Street facade of Gilbert Scott’s Foreign Office. Distracted by No 10, few people notice the incredibly skilful way Scott has designed a flanking elevation. (Photo: Ian Dungavell) |

Desperate to save the Foreign Office, the Victorian Society suggested that 'the whole block except for the best interiors could be "gutted" with new concrete-framed offices built within the existing facades, the main courtyard probably being scrapped’. This would have involved keeping the facades to Whitehall and St James’s Park, but the skylines only to Downing Street and King Charles Street. The great Durbar Court of the India Office was also considered ‘expendable’.

Thankfully, the loss of most of the buildings of Whitehall in favour of a more efficient bureaucratic machine was too much for most people to stomach and Martin’s ambitious (some would say megalomaniac) scheme was shelved. In 1964 the Victorian Society had been practically alone in thinking the Foreign Office should be preserved, but by 1970 it had been joined by all the principal preservation and planning bodies in the country. The buildings threatened by the redevelopment of Whitehall had then been listed.

Now that the building has been restored, the government is justifiably very proud of the Foreign Office. It attracts huge numbers of visitors whenever it is open to the public, as on Open House London weekends, most of whom would be horrified to think that the building was once seriously threatened.

This is a good sign that understanding and appreciation of our Victorian heritage is widening and deepening, but the old threats associated with traffic, population growth and economic cycles are still with us, and new ones such as climate change are emerging. There is still much for the Victorian Society to do.

~~~

Recommended Reading

Copies of Saving a Century, a commemorative publication by Gavin Stamp celebrating the work of the Victorian Society, are available from www.victoriansociety.org.uk (£5 including UK postage and packing).