Saving Our Historic Primary Schools

Ian Dungavell

|

|

||

|

|||

| Sensitive conservation enabled the character of this Victorian school hall at Fitzjohn's Primary School, Hampstead, London (above) to be revealed. It had been subdivided into small classrooms (top right). (Photos: Curl La Tourelle Architects) | |||

Under the Chancellor's recently announced £36 billion school building programme, half the primary schools in England and all the secondaries will either be rebuilt or refurbished within the next 15 years (The Independent, 7 December 2006). 'State of-the-art school buildings can improve educational standards and have a positive effect on everyone who uses them - pupils, teachers or the wider community', asserts a recent government mission statement (Schools Capital: Investment for All, DfES 1111/2004, p1).

But must 'state-of-the-art' facilities be housed in 'state-of-the-art' buildings? The evidence from the private sector and, indeed, many of our prestigious universities is that historic buildings are not incompatible with modern learning environments. Many of our most prestigious private schools have great 19th-century buildings: Rugby, Lancing, Dulwich and Wellington College are just a few of them. In these, the architecture is well cared for and has become inseparable from the reputation of the schools.

The danger is that in the excitement caused by perhaps the greatest influx of capital investment in school-building ever, our 3,400 primary schools built before 1919 (source: Mukund Patel, DfES) might fall victim to the rebuilding mania. Most of these are not listed and cannot be protected in that way, but that does not mean that they are not good buildings and worthy of preservation.

Some of these historic buildings have already gone. Recently, Bonner Street Primary School in Hackney, one of the early London board schools designed by E R Robson, was demolished. It was a handsome building and had the distinction of being the only board school illustrated by Dixon and Muthesius in their seminal book, Victorian Architecture, and there was a vigorous local campaign to save it. There was nothing wrong with the building, but it wasn't listed and it wasn't in a conservation area. Fatally, there was enough money available to build a new school.

Victorian and Edwardian primary schools fall into two broad groups. The parish or village school type usually had a large school room, off which opened one or two smaller classrooms. In towns they could be much larger and built on several storeys, but large schools are much more commonly found after the 1870 Education Act which established publicly-funded non-denominational state schools, called board schools, to supplement those already run by churches, charities and private individuals.

The architecture of school buildings contributes to local distinctiveness. Many parish schools were built using local materials. School boards used local architects and often developed families of buildings with a particular character. The designs of E R Robson in London, and of Martin and Chamberlain in Birmingham, for example, are important to the identities of these cities. By contrast, new schools usually have no locally distinctive characteristics. Indeed they often contribute to the decline in differences between regions and places.

SCHOOLS SHOULD PROVIDE WELL-DESIGNED AND UPLIFTING ENVIRONMENTS

The special qualities of original architecture cannot be appreciated if a building is neglected, and it is too easy to mistakenly blame a poor environment on the architecture. Improvements to the condition of school buildings can help to improve pupil performance through improving the morale of pupils and teachers alike, so continual maintenance and periodic upgrading should be part of the plan for all schools.

|

|||

|

|||

Above right: the harmonious design of the extension on the left enabled St Faith's Primary School, Winchester to double in size while retaining the interest of its original architecture (the two gables on the right), contributing to the character of the surrounding conservation area. (Photo: Genesis Design Studio) |

Where extensive alterations are required, Victorian and Edwardian schools offer a number of advantages over more recent buildings. Apart from their generally strong, adaptable fabric they often have wide corridors, high ceilings and large halls which give them a flexibility to adapt to changing educational needs.

By contrast, the minimum space standards which apply to new schools often become the maximum. Richard Slade, headteacher of the Joseph Lancaster School in Southwark, London, said 'DfES building regulations mean that classroom space in new builds is extremely tight... They seem to have been drawn up by accountants. As we are going for a refit of an existing building, we have extra space and I think children in urban areas need that'.

Are today's new schools better than old ones? A CABE report on the new secondary schools being built as part of the Building Schools for the Future programme found that their design was 'not good enough to secure the building the government's ambition to transform our children's education'. Half were assessed as 'poor' or 'mediocre', performing particularly badly 'on basic issues of environmental sustainability such as having natural daylight and ventilation'.

When planning alterations, schools should, with the help of an architect, step back and look at their needs. A good architect will get involved and talk to everyone, trying to respond to the particular character of the school and its context. 'Some schools have very concrete ideas about what they want and this is not always a good thing,' says Sarah Curl, of Curl La Tourelle architects. 'A simple list of the pros and cons of a school are a good idea. Proposed solutions can often be unrealistic.'

Architects may also find it easier to come up with a long-term vision for the school. Often additions and alterations have been made in a haphazard way over many years to satisfy immediate needs, and an architect is well placed to work out which of these may need to be done away with and which are worth keeping.

A SCHOOL HALL, REDISCOVERED

Fitzjohn's Primary School in Hampstead, London, was built as the school house for the Soldiers' Daughters' Home, designed by William Munt, 1856-58, and was taken over by the present primary school about a hundred years later. The headteacher, Cathy Joiner, described it as having the character of 'a small Victorian village school'. Indeed, it is typical of many smaller schools built before the 1870 Education Act, and a good example of gothic revival school design, with trefoil-headed lancet windows in Bath stone set in walls of Kentish rag. The entrance is beneath a two-storey tower with a broach spire, giving a churchy feel often found in parish schools.

|

|

| A new entrance adds an element of interest to the Hargrave Park School in Islington, London, but its magnificent brickwork remains disfigured by a century of grime due to a limited budget. (Photo: Ian Dungavell) |

However, the existing buildings did not provide sufficient space for the school's needs, and what it felt most keenly was the lack of a large hall. The school needed a place for performances, concerts, physical education, shared meals and parents evenings. Surprisingly the solution was close at hand, and the answer was not to build a new hall, but some extra classrooms.

The original main school room had been used for many years as infant classrooms, with thin partition walls dividing up the space. New classrooms were built to replace them in smart timber-clad pods which allow the listed building to maintain due prominence through their light construction and their layout. The new classrooms hug the boundaries of the site, and mature trees in the playground were retained. Natural lighting, high standards of insulation, grey water recycling and under-floor heating means that the new designs perform particularly well environmentally.

Once the new classrooms had been completed, the infant classrooms could be removed, returning the hall to its original form, but its decoration left a lot to be desired (see illustration at top of page). Brick walls had been painted, lighting was functional rather than inspiring, and surface-mounted ducting disfigured the walls. The progressive degradation of the interior was typical of what happens to many schools over the years. Nobody deliberately set out to wreck it. The result was simply the inevitable product of a series of incremental small-scale changes made to satisfy pressing needs and inadequate budgets.

The hall is now a recognisably Victorian interior, but with a very light, 21st-century feel. The timbers of the scissor truss roof were stripped back, and the floor sanded and sealed, so there is none of the dark wood the Victorians were partial to, but one wonders how well the white-painted wooden dado will wear. The ceiling was fitted with acoustic panels and the cabling for the new light fittings has been carefully concealed. 'I will never forget our first school assembly,' said Mrs Joyner. 'As the children entered there were audible gasps and mutterings of "it's beautiful". The school has always been successful, but now our environment matches our achievements.'

MAKING A BOARD SCHOOL BIGGER

|

Working with existing buildings demands that architects start by looking for the opportunities they present. When the Randal Cremer Primary School in Hackney, London, wanted to expand its intake, it was faced with the choice of squeezing more pupils into its 1890s building or losing a chunk of the playground to a new one, and nobody wanted to do that. Thankfully, in practice the alternatives were not so stark: they got what they needed and kept all but a sliver of the playground.

The architects began by talking to all the people involved with the school, including the children, to find out what was really required, and then tried to work out how to provide this within the existing building and the limited budget. The generous board school plan allowed them to identify areas of underused space which could be turned to good use, and the architects ended up taking a piecemeal approach, working all over the school. For example, the central hall on the first floor was adapted for an ICT suite and library, cleverly using partitions which avoided the need for mechanical ventilation.

As a result, only a small extension was needed. This they managed to tuck mostly in the narrow strip between the street and the building. This contained the Headteacher's office, the school administration and a new classroom, together with a new foyer, which substantially improved the security of the school.

One problem was how to handle the junction of the new with the old, here camouflaged not altogether successfully by a stainless steel monopitch roof. The elevation reads as a brick boundary wall in keeping with the existing one, but punctured with a number of randomly-placed glass portholes into the reception area. This presents a physically robust but welcoming and contemporary entrance. The elevations to the playground are clad in a softer and warmer untreated cedar.

'We like to think that we raise people's ambitions for the space beyond the merely utilitarian', said Alex Sherratt of Matthew Lloyd Architects. 'We want to lift their spirits through the choice of materials and forms. The image the school presents is very important'.

RE-THINKING CELLULAR CLASS ROOMS

|

|

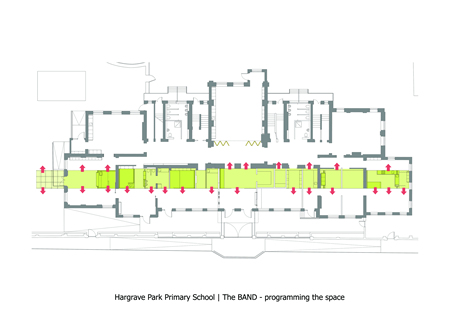

| A little colour and a great deal of imagination transform the interior of Hargrave Park School into a vibrant learning environment bisected by the band of green. (Photo, above: Edmund Sumner, Kay Hartmann Architects. Drawings, top: Kay Hartmann Architects) |

The refurbishment and alterations to Hargrave Park School in the London borough of Islington illustrate how contemporary styling can transform old school interiors without resorting to demolition. In this case the brief was relatively modest. A new children's centre was created for the nursery and reception class, as well as a new school office and an online learning centre for the local community, all within the existing ground floor of this three-storey board school.

A new main entrance was created in Bredgar Road, enhancing security and avoiding a more convoluted route across the playground. Two windows were dropped to form a pair of doors with a glass canopy over them, with new gates in an appropriately contemporary style in front. The decorative parts of the perimeter iron railings were retained and refurbished with new steel sections inset between. Unfortunately the budget did not stretch to cleaning the paint off the brickwork on the lower part of the school walls so this was repainted in an unobtrusive colour.

Inside, the new work is more assertive. Wishing to escape from the cellular nature of the classroom spaces, architect Kay Hartmann introduced a 'green band' which undulates like a broad ribbon from one end of the building to the other through the rear part of the front range, taking on different forms according to the function of the room it crosses. In the children’s centre it might be a climbing frame or a room within a room; in the entrance lobby it forms a bench; in the kitchen it is both canopy and table. Visually, it links the different rooms, but new openings have also been formed in the cross walls to further unify the spaces.

Apart from the 'band', a considerable improvement in the internal appearance was made through quite simple means: white paint throughout, new lighting and stripped and resealed floors. The result is a fresh, contemporary re-styling of a historic interior which retains and adapts historic fabric creatively. The wooden floors provide a feeling of warmth, the green band an energising dash of colour, and the white walls a quiet foil to the children's projects displayed on them.

THE FUTURE

All this new work in schools will itself face the same tendency towards disorder that degraded many of the buildings in the first place. Already at Hargrave Park a new noticeboard has been put up on the brick pier between the two front doors. It is crooked and off centre. When the cedar cladding at Randal Cremer weathers as intended to silvery grey, will its custodians resist the urge to get out their paintbrushes? Will future generations take the same view of our school extensions that ours takes of much of the 1960s work? At least when the next round of school capital investment appears in 40 or 50 years time, Victorian and Edwardian school buildings are likely still to be strong enough to cope with the adaptations demanded by a new era of educational thinking.

~~~