Cockrill-Doulton Patent Tiles

Judith Martin

Fine tilework in an early 19th century school building may be a rare example of Cockrill-Doulton Patent Tiles, an intriguing construction system using glazed ceramic tiles as permanent shuttering for poured concrete. Judith Martin appeals for more information.

All archaeologists know that the poor of any society leave fewer traces than the rich. Stone buildings endure better than mud huts. Gold survives while iron rusts. The builders of the great cathedrals can be tracked by their marks from Sens to Canterbury. Only odd accidents, like Pete Marsh or the chap in the glacier in the Alps, start to show what daily life might really have been like for the vast majority of people.

Leap forward a few thousand years and the same still applies, to the architecture for the poor in Victorian England. Most country houses are by known architects (if in doubt, attribute it to Inigo Jones), landscapers are household names; sometimes even the crafts people are known by name. But try to establish the sources of materials in the great number of buildings built by the philanthropists of the 19th century, and the trail soon goes cold. The numerous charitable bodies kept copious minutes, noting who attended what meeting, but their concern about how their buildings should be constructed seems not to go beyond the need for economy and resilience.

|

|

The Beaufoy Institute in Lambeth is a prime example. The Beaufoys were a family, possibly of Huguenot origin, who made their fortune from distilling. It is said that they made gin until one of their members saw a copy of Hogarth's Gin Lane and resolved to have no more to do with this terrible destructive force, turning instead to the production of vinegar. It is not clear whether they knew Lord Ashley, later Lord Shaftesbury, the founder of the London Ragged School Union, but they were charitably inclined, and in the 1840s Mrs Harriet Beaufoy established a Ragged School in the arches of the new railway on what was then Doughty Street (now Newport Street). Not wanting to impede the children's ability to work, schooling was provided only on Sundays, and was concerned almost exclusively with religious matters. Nevertheless, the ragged schools were the first step towards universal provision.

When Harriet died, her husband in her memory built a spectacular school to take its place in 1851. This had two wings flanking a portico and pediment, looking more like a gentleman's club than an establishment for barefoot children who needed feeding and delousing as well as schooling. It was an early example of architecture for the poor, and such standards were seldom if ever reached again.

|

The 1870 Education Act meant education was more formally available, and free, and the purpose of the Ragged Schools changed. In 1903 it was decided to sell the site to the Railway Company; one wing remains, looking remarkably like railway architecture. But the Beaufoy charitable impulse persisted, and with the money from the sale of the first school the trustees of the Ragged School, among whom were two Beaufoys and a Doulton, from the factory on the Embankment, built the Technical Institute that still bears the Beaufoy name, for young persons... of the poorer classes.

The Beaufoy Institute, in its terracotta, Arts and Crafts, glory, stands neglected on Black Prince Road, empty since the demise of the Inner London Education Authority in 1990. It is listed Grade II. Externally it is decorated with swags of fruit, plaques with the dates 1851 (the first school) and 1907, and the rather lovely carving that came from the first building 'Those that do teach young children, do so through gentle means and easy lessons'. Internally, it is far plainer, with tiled walls, brown below, cream above, and no decoration beyond the hall. It is the stairs that are first really remarkable, and then, in the basement, the urinals. Both are of brown, salt-glazed ceramic, the handrail and baluster unlike anything the current writer has ever seen. It is tempting to say they are unique, and yet logic says they were off-the-peg.

Circumstantial evidence points clearly to the Doulton factory, part of whose showroom remains further down Black Prince Road, and whose chairman was a fellow trustee with the Beaufoys. And yet there is nothing in the Beaufoy papers to say where the materials came from. The principal writer on Doulton ceramics, Desmond Eyles, says of his research, one great difficulty was the seeming dearth of records. The factory on the Embankment suffered a flood, and the showroom on Black Prince Road was bombed. There are catalogues and there have been exhibitions, but it is the fancy ware that most people find interesting, not the functional architectural stuff that actually made the firm's fortune.

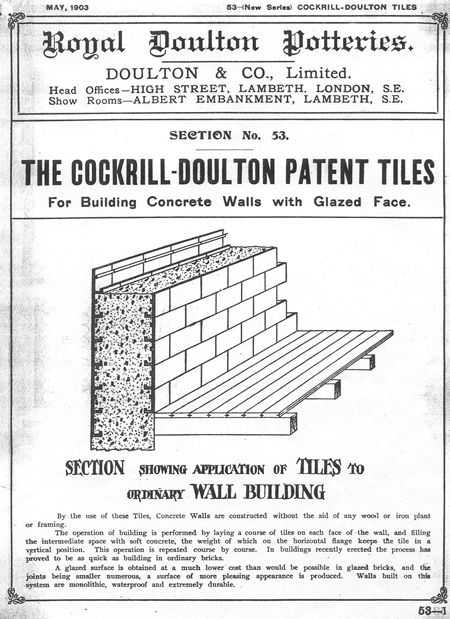

There are, however, two incomplete catalogues of sanitary and building ware in the Lambeth archives, dated 1903 and 1904 - just in time for the Institute. There is something that might, perhaps, be the urinals, but there is no sign of the staircase. What there is, though, are several pages on Cockrill-Doulton Patent Tiles. Suddenly the construction method of those brown and cream walls is clear.

J W Cockrill - Concrete Cockrill, apparently, to his friends - was borough engineer of Great Yarmouth between 1890 and 1903. A page in the catalogue shows a delightful little pumping station, urinal and shelter built in Great Yarmouth in 1900. Sadly it is no longer standing, but the catalogue shows a single storey building with classical detailing and a nice curvy roof.

How Concrete Cockrill came to meet the rather grand Doultons is not known, but the patent tile in their joint name is remarkable. The system, says the catalogue, provides a glazed surface... at a much lower cost than would be possible in glazed bricks, and the joints being smaller and less numerous, a surface of more pleasing appearance is produced. It goes on to say 'The operation of building is performed by laying a course of tiles on each face of the wall, and filling the intermediate space with soft concrete, the weight of which on the horizontal flange keeps the tile in a vertical position. This operation is repeated course by course.'

Tile experts who have seen this description tend to be disbelieving and no-one seems to have come across the method before. Was it so cheap and successful that it was used widely on those undocumented buildings for the poor, or was it in fact so fiddly - surely it needed shuttering, and could only be raised a course at a time? - that, after being trialled on the Beaufoy Institute by the friend of Doulton, it was never used again?

Probably the truth is somewhere between these two poles, but seldom has a construction method vanished so completely without trace. It could still be in many early 19th century buildings, assumed to be ordinary tiles or glazed bricks, or perhaps panelled over as it is so hard to drill into. While the (hideous, mostly) jugs and vases from the Doulton factory tell us about the tastes and disposable income of the new middle classes in the 19th century, where are the records of the poor who worked in their factories, or cleaned their chimneys, or swept their streets?

Of course they were documented, factually by pioneers like Booth and fictionally, for a vast market, by Dickens. It is also true that many buildings for the poor, like the early Peabody estates and the Beaufoy Institute itself are far more loved than many later versions; the Institute became part of the Lilian Baylis School, whose 1960s building, now also listed, is beloved only of English Heritage. But the fact remains, to the frustration of researchers, that the material fabric of the provision for the poor was much less important at the time than the provision of spiritual sustenance to keep them on the straight and narrow.

~~~