Imitation Timber Graining

in the 18th and 19th Centuries

Lisa Oestreicher

|

|

| The Balcony Room at Dyrham Park near Bath, and (below left) a detail of the walnut graining scheme on one of the shutters. Paint research revealed that this was the room’s second decoration scheme and was probably applied in the early 18th century. |

Today we are accustomed to seeing architectural joinery painted a plain colour, often white. However, this has not always been so. When investigating the layers of paint which accumulate in historic buildings over the centuries, the architectural paint researcher becomes accustomed to identifying the build-up of coloured opaque, translucent and varnish layers which are the tell-tale signs of the presence of graining.

This form of decoration was often used to make common timber such as deal look like more expensive wood. It is found in buildings of many styles and periods, from the modest to the grand, and its use within a room can range from one or two timber features to covering all the visible joinery from the glazing bars of the windows to the wainscoting and skirting boards.

From the examples found and from contemporary accounts, it is clear that graining was used continually as a decorative technique over the 200 years under consideration, although its popularity grew and waned according to the architectural taste of the day.

Generally speaking graining was considered fashionable during the Baroque period at the end of the 17th and beginning of the 18th centuries, but fell into decline during the Palladian and neo-classical periods of architecture. It found favour once again in the Regency period in the opening decades of the 19th century and remained a strong decorative force until the reforming influence of individuals such as John Ruskin and AWN Pugin in the middle of the century declared such imitative work a sham. Regardless, graining continued to be used in many buildings, but it does not appear to have recovered critical acceptance until the last quarter of the century. It is interesting to note that the popularity of some woods over others also changed during the period.

HOW GRAINING WAS USED

At a time when softwood was almost always painted, the principal aim of graining was not only to provide pattern and richness to an interior, but to give an impression that a more expensive timber had been employed. The most commonly imitated wood was oak, no doubt because of the long tradition of its use in Britain and the familiarity of its figuring. Other popular hardwoods included walnut and mahogany, which could convey an even greater degree of luxury.

As the decorator’s manuals of the day suggest, the techniques involved in the execution of graining could be relatively simple or they could involve the intricate application of many strata.

|

One such elaborate graining decoration was identified on all the joinery in the Octagon Room at Attingham Park, Shropshire, including the entrance door and its architrave, the window cases and architraves, built-in bookcases, skirting boards and dado rails. The property had been built to the designs of Charles Steuart in 1785, but it underwent extensive redecoration for the second Lord Berwick 17 years later, in 1812-13.

Lord Berwick had recently married and was spending large sums of money to bring his property in line with current London Regency architectural tastes. This was reflected in the lavish style of decoration he employed in the Octagon Room, which was adapted for use as a study. The extent of the alterations also contributed to Berwick’s downfall, as his expenditure at Attingham far exceeded his fortune and he was made bankrupt in 1827.

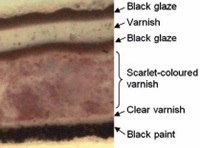

Initial analysis indicated the presence of a complex manipulated scheme consisting of multiple opaque and translucent red layers as well as varnish coatings applied over a black ground. There was some evidence to suggest that hard particles of grit had been added to this base coat to lend it variety and texture. The scheme was probably intended as an imitation of rosewood. The analysis, coupled with uncovering trials, allowed for the scheme to be successfully reproduced by the National Trust, lending the room back some of its original Regency opulence.

Despite the popularity of graining at this time, the technique was by no means ubiquitous, and the absence of graining in a building can indicate a specific aesthetic choice and approach to interior decoration. This eschewing of imitative painting techniques was evident in the early 18th-century Quaker meeting houses in both Ringwood, Hampshire and Bristol. In its place plain solid colours were used to decorate the interior woodwork.

Another omission of particular interest can be found in the much later example of William Morris’s Red House in Bexleyheath, London, which was designed by Philip Webb in 1859-60. A riot of colour, patterned decoration, wall paintings and textiles were identified as forming part of the property’s initial interior design. However, not one example of original graining was pinpointed. In many ways Red House was the testing ground where Morris experimented with design ideas that were to later find form in his commercial work in the closing decades of the 19th century. His avoidance of imitative techniques such as graining was, for Morris and his cohorts, a statement of intent.

|

|

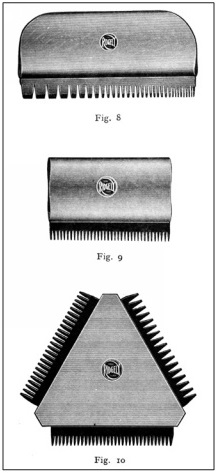

| Graining tools (Photo: Hare & Humphreys Ltd) | Victorian oak graining with ‘lights’ running across the grain |

PATTERNS OF USE

In the early 18th century it was not uncommon for wainscoting, including the skirting, to be grained. At this time it was normal practice to imitate only one timber within a room and the more complex juxtaposition of different timbers was rare. This rule was also normally true within a suite of rooms relating to one another, where each of this series of rooms was grained in imitation of the same timber.

In broad terms, through the Palladian period much of the joinery framework within a room was painted white, including the dado and the window and door architraves. As a consequence, imitation graining was restricted to the doors and sometimes the windows also. Later in the century, the neo-classical style introduced colour to the timber framework, and the use of graining was restricted once more to doors and occasionally windows, if used at all.

|

|

| Early 20th century ‘Ridgely’ graining combs illustrated in The Modern Painter and Decorator (see Recommended Reading) | |

|

|

| Oak graining uncovered during the investigation of the dairy complex at Kenwood House, Hampstead (Photo: Jane Davies Conservation, by courtesy of EH) |

The approach was to change in the Regency period when the use of graining became more prominent in interiors. No longer restricted to the door face, it was applied to any of the timber surfaces within a room such as dados, windows, shutters, architraves and, of course, doors. Although in some more elaborate interiors such as those found at the Brighton Pavilion created for the Prince Regent at the beginning of the 19th century, examples could also be found on the timber ceiling. More and more exotic timbers were imitated and less thought was given to restricting a room to one type of timber only. The result was that these various finishes vied for the attention of the visitor’s eye.

Despite objections to the art of imitation from some quarters, in general the fashion for graining grew in the Victorian period. Examples of its use could now be found on all timber surfaces within a room. Furthermore, as its appeal broadened it could be found in more humble abodes, and by the 1830s graining was being championed for use in cottages.

TECHNIQUES

It is clear from an examination of builder’s manuals that there is a change in the grainer’s objective over time. While in the early 18th century the painter sought to give an impression of graining, stylistically it remained a decorative and fanciful feature. However, in the 19th century there was an ever increasing tendency to take nature as a model in order to recreate an accurate copy of the wood in question.

Inherent in this change of objective was a shift in the techniques employed. In the early 18th century manuals indicate that the graining pattern was built up principally through the application of shading in opaque colours, while translucent glazes were favoured in the Regency and later periods to evoke the appearance of the decorative timber. Despite this trend, there is evidence to suggest that these two approaches existed side by side, with the former representing a cruder more primitive form of graining than the latter.

Although mention is made in decorator's manuals in the 18th century of graining or flat brushes being used for shading, there is limited account of any other tools. In the following century the documented range of tools available for decorative graining was quite extensive, culminating in a range of patent mechanical aids. However, each grainer would have had his favourite method of working and would have chosen tools according to his experience, the intended medium and the wood to be imitated. Therefore, although the potential choice was large it was not considered necessary for the grainer to have at any one time an extensive collection of equipment.

The two forms of graining most commonly executed by decorators in the 18th and 19th centuries were oil and distemper graining. In essence, oil graining is based on oil paint (traditionally white lead and pigment in linseed oil), while distemper graining is water-based, typically containing a soft distemper of chalk and pigment bound in size (animal glue) and diluted with beer. In practice, these two methods were sometimes mixed and it was not unusual for the final graining product to be the result of a combination of these two techniques. The more protective nature of an oil medium meant that external work was invariably executed in oil.

As described earlier, more primitive methods of graining relying on the sole use of opaque colours existed and were widely used. However, the techniques outlined below focus on the more advanced method involving translucent glazes over opaque grounds as gleaned from a reading of the decorator’s manuals of the day, and in practice a variety of techniques have been found to have been used. The following account is therefore most useful as a guide to understanding the complex schemes discovered by conservators.

OIL GRAINING

With oil graining the first task of the grainer was to apply the ground on which the later paint or translucent coloured glazes were to be laid. The ground was opaque, preferably with a matt finish and coloured so that it was slightly lighter than the lightest portion of the wood to be imitated. This lighter shade was to compensate for the slight deepening of colour which would be rendered by the finishing varnish.

Next came the application of graining colour, or ‘rubbing in’. The graining colour often included a mixture known as ‘megilp’, which helped to prevent the paint flowing together after manipulation, without impairing its translucency.

Megilp could be made with many different recipes depending on the experience and preferences of the decorator and its manufacture was often a closely guarded secret. However, one standard recipe often described in early 18th-century texts included sugar of lead (lead acetate), rotten stone (a type of weathered limestone which includes a high proportion of crystalline silica), white beeswax, turpentine and linseed oil.

|

||

| Octagon Room, Attingham Park, after completion of graining | ||

|

|

|

| Octagon Room, Attingham Park: close-up of completed graining |

Cross-section of the Octagon Room's Regency graining scheme | |

The graining colour was applied evenly and thinly in order to accentuate its translucency, then the initial phase of marking the grain began while it was still wet.

To create the effect of an open-grained wood such as oak, combs were used to produce the initial impressions of grain. Sponges and flat brushes were generally employed to create the effects of more close-grained woods such as mahogany. After this initial modelling the figures or ‘lights’ (see fourth illustration), which tend to run at cross angles to the grain, were created by wiping out the colour. This was normally achieved with a rag folded two or three times and placed over a thumb-nail or piece of bone.

In order to ensure that these lights did not appear monotonous, it was recommended that they were drawn in varied patterns as seen in nature. The work was then left to dry.

Where knots were required, these could be imitated immediately after the graining colour had been applied by removing a large round spot with a rag and by creating lights above and below. A badger-hair brush was then normally used to soften and blend the edges of these lights.

When the graining was complete the knot could be painted in with a sable pencil. It was considered more natural, particularly on door panels, if knots were placed to the side instead of in the centre of the work.

The next step was overgraining. This term was normally used to describe the application of colour, in water or oil colours, to selected areas to deepen and enhance the appearance of the imitated wood through the use of shade. Overgraining either warmed or cooled the tone of the oil graining, according to requirements. This overgraining then required softening, usually with a badger-hair brush, to give it a natural appearance.

The grained work was normally finished with varnish. In order to ensure an even surface, varnish layers were rubbed down between applications – with as many as eight coats recommended in the manuals of the day. It was then usual practice for the final varnish layer to be polished.

DISTEMPER

In most instances the ground used in oil and distemper graining was the same. In the latter, it was suggested that, once the ground was dry, it should be wiped with a damp cloth as this would allow the distemper colour to adhere better. Distemper graining pigments were often ground very finely in beer and thinned for use with weak beer and water.

The graining colour, sometimes with the addition of megilp, was applied with a large sponge or with a flat brush. Only small areas could be worked on at any one time as the distemper paint dried quickly. Rubber or steel combs could be employed but tools such as veining brushes and sponges were also used according to the effect required. Lights and knots could be further wiped out with a rag. If the final appearance was not as desired, the graining layer could be washed off and the procedure started again.

If the overgraining was executed in distemper it was often bound with strong beer, vinegar or a combination of the two and was not applied until the grained layer beneath was dry. In general, water colours adhere well to oil graining but a stronger mix was required than if the preceding graining layer had been executed in distemper. It was also important that the distemper overgraining was sufficiently strong for it to remain fixed when varnished. As a distemper medium gave less protection to its constituents than oil, the work was almost always varnished.

|

|

| Recreation of imitation harewood (above left) and satinwood graining (above right) undertaken as part of the conservation and restoration of Sir John Soane’s townhouse at No 12 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London. (Photos: Hare & Humphreys Ltd) | |

THE PRESENT DAY

The use of graining waned after the first world war, not least because the technique is so labour-intensive, and the rise of Modernism sealed its fate. However, wherever thick layers of paint remain on historic joinery, evidence for decorative wood graining schemes may well lurk beneath. Clearly, this paintwork is a rich repository of information which can reveal not only where and when graining schemes were used, but also the types of wood that were being imitated.

Paint stripping prior to repainting will reveal the lines of the original mouldings more clearly, but the secrets contained in that layer of paint will also be lost forever. If paint analysis cannot be carried out before it is stripped, careful thought should be given as to whether it is really necessary to strip all the paintwork, or whether there are areas that could be over-painted.

~~~

Recommended Reading

IC Bristow, Interior House-Painting Colours and Technology 1615-1840, Yale University Press, London, 1996

EA Davidson, A Practical Manual of House Painting, Graining, Marbling and Sign Writing, Lockwood & Co, London, 1875

J Fowler and J Cornforth, English Decoration in the Eighteenth Century, Barrie & Jenkins, London, 1986

C Gere, Nineteenth-Century Decoration: The Art of the Interior, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1989

AS Jennings, The Modern Painter and Decorator: A Practical Work on House Painting and Decorating, Caxton Publishing Company, London, c1947

P Nicholson, The Builder’s and Workman’s New Director, A Fullarton and Co, London, 1854

J Pincot, Pincot’s Treatise on the Practical Part of Coach & House Painting, London, 1811

PF Tingry, The Painter’s & Colourman’s Complete Guide, Sherwood Gilbert and Piper, London, 1830

N Whittock, The Decorative Painter’s and Glazier’s Guide, London, 1827