Saving Time

A review of the conservation movement in Britain in the 20th century

Michael Pearce

Government advice in 1972, in Lord Sandford's words, called for the

preservation of the 'familiar and cherished local scene', but much had

already been lost at a time of unprecedented change.

Most historic towns were still recognisable to the older generation at the end of the 19th century. Only a few uninhabited monuments needed to be scheduled. The Society for the Preservation of Ancient Buildings had been formed in 1877 by William Morris to oppose excessive restoration work to churches. The National Trust for England, including Wales and Northern Ireland, had been founded in 1895 to counter threats to the Lake District. The Victoria County Histories were begun in 1904, and the Royal Commissions' inventories of historical monuments in 1908. New volumes are still being published.

|

||

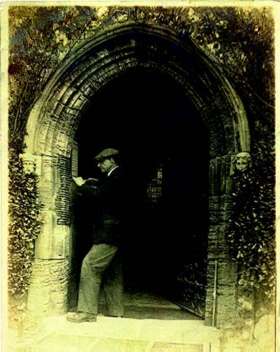

| SPAB

repairs at Rottingdean Church, Sussex in 1930. The work of the Society in preserving traditional craft skills underpins the current revival in the use of lime mortars and other traditional repair techniques. Their influence on conservation in the UK today cannot be overstated. Reproduced by kind permission of The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. |

The old order was shattered by the losses of the First World War. Instead of a gradual process of change, many of the younger generation, and the survivors, tended to reject all that had led up to the war in favour of a brave new world. The Modern Movement was cast in concrete. Many of their high-rise flats, cinemas, lidos, zoo buildings, and tube or bus stations are now listed, but many unfashionable Georgian buildings were lost. In defence, the Ancient Monuments Society was formed in 1924, and the Georgian Group in 1937. They were encouraged by the architectural historian John Summerson and others in the wake of the redevelopment of Regent Street and the Adelphi, and the threatened loss of Carlton House Terrace in London. In Scotland, extensive slum clearance caused the loss of many attractive vernacular buildings, prompting the Marquess of Bute and others to form the National Trust for Scotland in 1931. The Trust was responsible for the first lists of historic buildings, and through the Little Houses Schemes, at Culross initially, demonstrated that whole areas of historic buildings could be conserved rather than redeveloped.

London and many other historic cities

suffered extensive bomb damage in the Second World War, but important

buildings were listed and photographed. The lists were extended into

a national survey by the planning Acts of 1944 and 1947. The photographs

helped the restoration of selected buildings and formed the basis

of the National Buildings Record. Many more buildings were demolished

after the war. Space was urgently needed for new houses and flats,

as well as for new roads. In the country, many houses had been requisitioned,

abandoned, or demolished. On the recommendation of the Gowers committee,

The Historic Buildings & Ancient Monuments Act 1953 introduced

limited grants for outstanding buildings on the advice of Historic

Buildings Councils for England, Scotland, and Wales. Grant giving

powers were extended to local authorities in 1962.

Since 1932, the demolition of an historic building had been controlled

once the minister had confirmed a building preservation order but,

in practice, it was too slow. Only through publicity for losses could

sufficient interest be raised to oblige authorities to act, or to

change the law. The Buildings of England series encouraged that interest,

the first being Cornwall in 1951. We owe a great debt to Nikolaus

Pevsner, to his successors, and to Penguin Books who have kept the

volumes revised and in print. With encouragement from Pevsner, Betjeman

and others, the Victorian Society was founded in 1958, and other societies

for later periods and particular interests have followed.

|

|

| Wartime

damage at St Mary Arches, Exeter, 1942. The photograph was taken by Mary Tomlinson shortly after the church was hit. She was one of a handful of photographers employed by the then newly formed National Buildings Record (now the National Monuments Record at English Heritage) to record historic buildings under threat. Reproduced by kind permission of the National Monuments Record. |

The Civic Trust was founded by Duncan Sandys in 1957. Under the direction

of Michael Middleton and assisted by Gordon Michell, its professional

adviser, it encouraged the creation of a thousand local amenity societies.

Piccadilly Circus was saved from redevelopment. The demolition of

the Euston Arch, approved by Harold Macmillan in 1961 despite every

effort to save it, followed by the demolition of the Coal Exchange

in 1962, finally provoked such public indignation that the tide of

destruction began to turn. In 1967, Duncan Sandys brought in the Civic

Amenities Act to establish conservation areas and, having defeated

plans for an inner ring road in Edinburgh, the Scottish Civic Trust

was founded. The Government published Preservation and Change, acknowledging

that 'many buildings of grace and distinction have been lost'. Planning

legislation was strengthened. At long last the Town & Country

Planning Act 1968 made it illegal to demolish a listed building without

consent, although other buildings in conservation areas were not protected

until six years later. Following the Pastoral Measure 1968, the Redundant

Churches Fund was formed which, reconstituted as the Churches Conservation

Trust in 1994, now has the care of over 300 historic churches of the

Church of England. In 1968 the Government also commissioned studies

of four historic towns, York, Chester, Chichester and Bath, which

led to an influential report to the Secretary of State from Lord Kennet's

Preservation Policy Group in 1970. In the same year, Robert Matthew

and others formed the highly successful Edinburgh New Town Conservation

Committee. In London, Covent Garden market had been listed in 1958,

but the streets around it continued to deteriorate. In 1973, encouraged

by Jennifer Jenkins, later Chairman of the Historic Buildings Council

for England, Geoffrey Rippon listed over 200 buildings, particularly

on street corners. For the first time, plans for new roads and comprehensive

redevelopment, which had survived a public inquiry, were abandoned

in favour of conservation.

The continuing destruction of the country house was highlighted by

an important exhibition at the V&A in 1974. It made a fitting

prelude to European Architectural Heritage Year 1975, co-ordinated

by the Civic Trust on behalf of the Council of Europe, which again

captured the public interest. The formation of many charitable building

preservation trusts was a lasting benefit. Instead of letting property,

as the pre-war cottage improvement societies had done, the new trusts

acted as revolving funds by buying and selling the buildings they

restored with protective covenants. The Architectural Heritage Fund

was created to offer loan capital on favourable terms.

SAVE Britain's Heritage also dates from 1975. Marcus Binney, the architectural

editor of Country Life, and other historians and journalists, formed

a fearless and powerful combination. They were prepared to fight public

local inquiries, prosecute illegal demolition or, if necessary, serve

writs on the Secretary of State. Barlaston Hall, which they bought

during the course of one inquiry, has now been restored.

Where then were the local planning authorities which were supposed

to be in the front line? The House of Lords debate on The Local Government

Act 1972 highlighted the difficulties for smaller authorities in obtaining

specialist advice, citing continuing demolition in Bath as an example.

Roy Worskett was appointed from the ministry to be the city architect

and planning officer. From 1974 planning powers were devolved to the

districts, to include the former county boroughs, but the county councils

were given overall reserve powers, and London retained the GLC. They

could all work together. Given sympathetic members and chief officers,

any of their functions could be regarded as containing an element

of conservation and be funded accordingly. A building preservation

trust, as a charity, could harness public interest. With a combination

of political and financial ingenuity, Hampshire, Derbyshire, Essex,

and Kent went into action, and others followed.

|

|

| 20th century disasters: The Firestone building, Middlesex (above), a spectacular example of 1930s Art Deco, demolished in 1980 as it was about to be listed; and The Euston Arch, London (below left) demolished in 1961 despite a public outcry. |

The co-operation which developed between the county conservation officers was made available to help the Crafts Council produce a Crafts Skills Register in 1981. In order to maintain that co-operation, they formed the Association of Conservation Officers. Membership extended to all local authorities and later into private practice and now forms the basis of the Institute of Historic Buildings Conservation.

The introduction of listed building consent in 1968 revealed the inadequacy of the statutory lists. Many buildings were still on the provisional list, large parts of rural areas had never been surveyed, and few buildings built after 1840 were listed. Resurvey began in 1970, but there were too few inspectors, and too much of their time was taken up by the contentious late listing of buildings at risk. Some local authorities, including Hampshire, offered their own lists for approval.

The inevitable disaster came in 1980. The listing of the 1930s Firestone building in west London was pre-empted when its frontage was demolished over the August bank holiday. As a result, Michael Heseltine, as Secretary of State, approved an accelerated national resurvey. It was completed by 22 local authorities and 11 private practices in 1987. Listing today concentrates on particular building types and selected buildings over 30 years old.

|

Given that the National Trust had achieved enormous success as an independent organisation - by that time it had over one million members - Michael Heseltine thought that it would be cheaper for the Treasury if the monuments in his care were held by a semi-independent government agency. English Heritage was launched in 1984, but it has never really had the resources it needs. Though the monuments are better presented, it has to be very selective in what it can do. Its grants for historic buildings and areas are limited and increasingly supplemented by the much larger Heritage Lottery Fund. Its limited number of professional staff, now regionally based, must concentrate on selected cases. Its academic reputation, however, has been strengthened by the addition of the staff of the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments for England. Historic Scotland was established in 1991.

It has the advantage of a more co-ordinated system than in England in that its heritage functions are combined with those of the Department of the Environment Transport & Regions and the Department of Culture Media & Sport. Heritage interests in Wales have since 1984 been represented by Cadw, which in 1991 became an executive agency on similar lines to Scotland, and in Northern Ireland by the Government Office.

It is encouraging to note that public reaction to the loss of historic buildings has generally prompted a positive response, though one would rather not have suffered the losses.

Two other aspects deserve mention. Firstly, far more is now known and published about the history of buildings, so that any debate is better informed. Thanks to Cecil Hewett's studies of carpentry, and the advent of dendrochronology, historic buildings are now more accurately dated. Secondly when, as at Uppark, Hampton Court or Windsor Castle, important buildings have been damaged by fire, they are now more likely to be repaired than demolished. More care is taken with fire protection and salvage plans. The positive outcome of these disasters has been a major advance in the availability of specialist skills, materials, and techniques.

|

|

| The Grange, Northington, Hants. Remodelled by William Wilkins 1804-09, this most important country house was saved from destruction following the V&A exhibition in 1974. |

Local government, however, is not as strong as it was. Financial autonomy

has been eroded, and many of the boroughs once again stand alone as

single tier authorities. Given that their functions are increasingly

monitored and directed by Whitehall, authorities may have difficulty

in attracting the imaginative people they need, either as members

or officers. Given the need to respond to all applications within

targeted times, and the need for extensive consultations, they may

find they have little time to compete for grants from national sources

or to promote positive action.

Though the rate of loss of historic buildings has been reduced, those

that survive are increasingly outnumbered by new buildings to accommodate

a population which nearly doubled in the 20th century. Today, only

two percent of buildings are listed, and in many towns they are overshadowed

by modern buildings of a wholly different scale and character which

would have been better sited elsewhere.

What of the future? The care of historic buildings will then be in

the hands of the next generation, but the time allowed for a proper

understanding of history in the national curriculum is increasingly

under pressure, which must be a matter of concern. The helpful influence

of the hereditary peers, who do know their history, has largely been

lost.

Historic towns were designed for people, not for unlimited numbers

of motor cars and 40 ton articulated lorries. It is perhaps a sad

reflection on the past century that motor vehicles now take up more

space than we do. It may only be a matter of time before someone decides

to list the earliest example of a multi-storey car park, or schedule

the remains of an original length of the M1 north of Luton, but let

us hope we never see it.