The Tower of Glass

An Túr Gloine and the early 20th century stained glass revival in Ireland

Nicola Gordon Bowe

Wilhelmina Geddes; detail of The Daughters of Music Brought Low, All Saints, Laleham, Surrey, 1926

Wilhelmina Geddes; detail of The Daughters of Music Brought Low, All Saints, Laleham, Surrey, 1926

In an article in the July 2008 issue of Ecclesiology Today (Appreciating Victorian and Arts and Crafts stained glass: a battle half won), Matthew Saunders laments the lack of informed critical appreciation in England of the many outstanding windows made during the second half of the 19th and the early 20th centuries.

He observes that the scholarship and photography of Martin Harrison and Peter Cormack are all too rare in their persuasive championship of great but commonly overlooked stained glass windows, and points out that documentation is often lacking on the artists and makers of the most vulnerable of all artistic expression within a church.

As Saunders notes, these individuals are rarely recognised in exhibitions or publications beyond the laudable Journal of the British Society of Master Glass-Painters.

Although there is no evidence of any pre-18th century tradition of stained glass production in Ireland, Ireland's 19th and 20th century glass has recently become the focus of Dr David Lawrence's meticulously chronicled and illustrated database, Gloine, which was funded by the Representative Church Body and the Heritage Council.

More than 1,300 windows in selected Church of Ireland churches have already been recorded in this ongoing database. A further offshoot of this project, initiated in 1991, has been Lawrence's informative Irish Heritage Council booklet on The Care of Stained Glass (2004). Through this and a number of other projects and publications over the past 20 years or so, the early 20th century achievements in stained glass of Harry Clarke and the artists of An Túr Gloine (the Tower of Glass) have been carefully documented, conserved and brought to the attention of a steadily expanding audience.

Among other examples of stained glass that have literally taken his breath away, Saunders singles out a major work, The Crucifixion (1922), by the Irish artist Wilhelmina Geddes at St Luke's, Wallsend, Newcastle: 'To see this Geddes is to recognise, like scales falling from the eyes, that nothing quite matches the highest quality stained glass for intensity of artistic experience. I stared at and absorbed it for a good ten minutes. Only a personal visit can suffice, photographs cannot convey the way it commands the whole interior'.

As Saunders notes, even Alec Clifton-Taylor admitted that the work had great power (although, like Pevsner, Clifton-Taylor mistakenly attributed it to Evie Hone).

Wilhelmina Geddes, The Crucifixion, St Luke’s, Wallsend upon Tyne, 1922 (Photo: 2008 Stuart Paul Sime, Three.Six.Nine. Photographic)

Wilhelmina Geddes, The Crucifixion, St Luke’s, Wallsend upon Tyne, 1922 (Photo: 2008 Stuart Paul Sime, Three.Six.Nine. Photographic)

In Victorian Stained Glass (1980), Martin Harrison describes Geddes' reputation as having been unfairly overshadowed by her more famous pupil, Evie Hone, and comments that her stunningly powerful crucifixion window at St Luke's, Wallsend, and her St Christopher window for All Saints' Church, Laleham (1925) must have been a severe shock to the genteel supporters of the Liturgical Movement who wanted their church interiors pale and chaste.

Peter Cormack, in the catalogue of his 1986 landmark exhibition Women Stained Glass Artists of the Arts and Crafts Movement at the William Morris Gallery, singled out Geddes' monumental style, which brought a new dimension to the [English] Arts and Crafts idiom in which she had been trained and which had a significant influence upon some of her contemporaries, notably Evie Hone.

John Piper, unique among 20th century English painters in understanding the traditional painterly and architectural tenets of stained glass, wrote in his seminal text, Stained Glass: Art or Anti-Art (1968) that, after the tide of the browns and mauves and plentiful dirty whites, and the demoralised Gothic of establishment Edwardian windows, it was through the sympathetic influences of Harry Clarke, Wilhelmina Geddes and Evie Hone that positive constructive relations were again established between stained glass and painting. Ireland had a strong influence at this time.

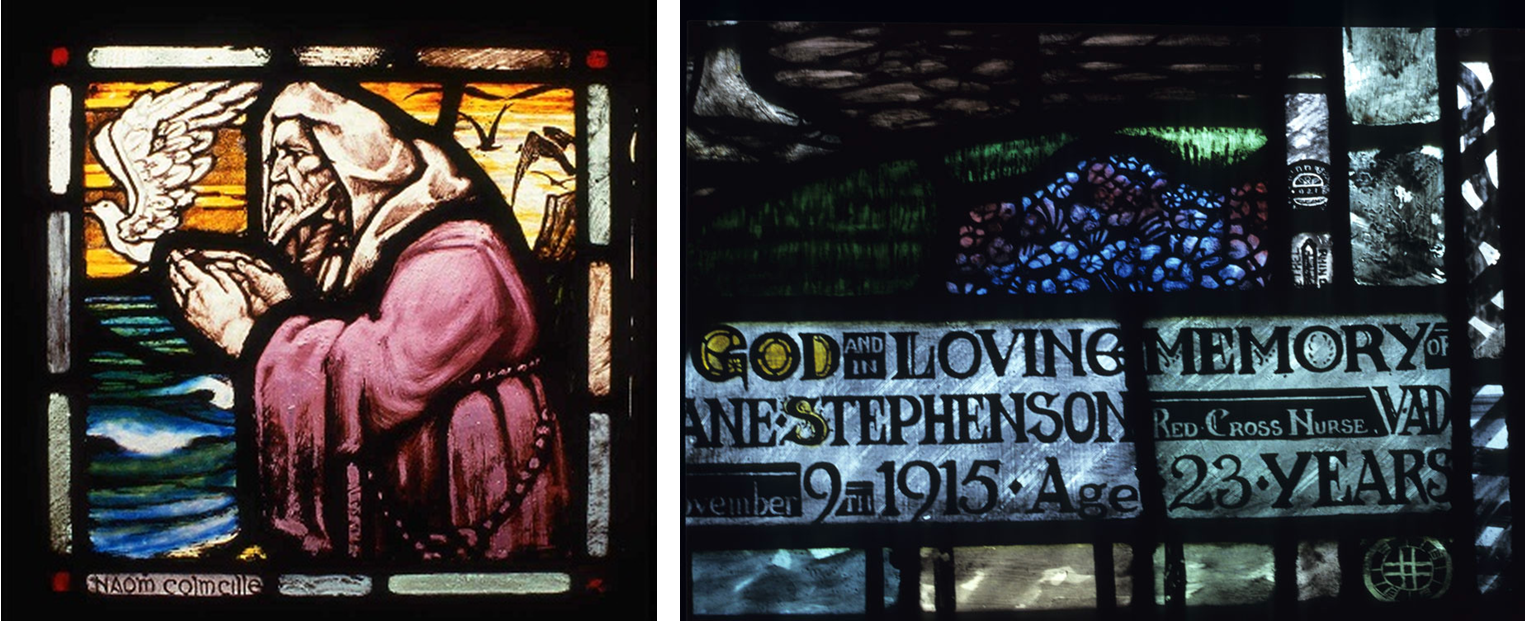

Left: Sarah Purser, St Columcille, private collection, Cork, c1910. Right: Ethel Rhind; detail of An Túr Gloine trademark and miniature tower with artist’s signature from the window of The Good Shepherd, Mary of Bethany and David (1921) at St Peter’s, Wallsend upon Tyne.

Left: Sarah Purser, St Columcille, private collection, Cork, c1910. Right: Ethel Rhind; detail of An Túr Gloine trademark and miniature tower with artist’s signature from the window of The Good Shepherd, Mary of Bethany and David (1921) at St Peter’s, Wallsend upon Tyne.

The Foundation of An Túr Gloine

The late Dr Michael Wynne estimated that there were over 100 glaziers working in Ireland in the 19th century.

Competing with the large foreign commercial firms to fill the many Roman Catholic churches built after Catholic Emancipation, and the Board of First Fruits and post-Disestablishment Church of Ireland churches which then proliferated, their standards were as variable in Ireland as they were elsewhere in what was still then the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

It was only with the emergence of the Celtic Revival and the cultural search for national identity and political independence at the end of the century that a handful of key critics, artists and patrons called for native stained glass production of a high quality.

They stipulated that this was to be produced by specially trained Irish artists using the best materials and a recognisably Irish iconography, rather than the ubiquitous pattern book designs for windows offered by most commercial trade houses.

So it was that in September 1901 Alfred Ernest Child arrived in Dublin to take up the post of Instructor in Stained Glass at the newly reorganised Dublin Metropolitan School of Art.

Evie Hone, The Annunciation and two abstract panels, St Nahi’s, Dundrum, Dublin 1933-4.

Evie Hone, The Annunciation and two abstract panels, St Nahi’s, Dundrum, Dublin 1933-4.

His arrival followed negotiations between the eminent painter Sarah Purser, the poet WB Yeats, the art collector and writer Edward Martyn, and Christopher Whall, the influential leader of the Arts and Crafts stained glass revival in England (the latter both Catholic converts).

Trained and deeply influenced by Whall, Child was to impart his master's principles to a new generation of Irish artists who would form the nucleus of a co-operative stained glass workshop set up along the lines of Mary Lowndes and Alfred Drury's purpose-built stained glass workshop in London.

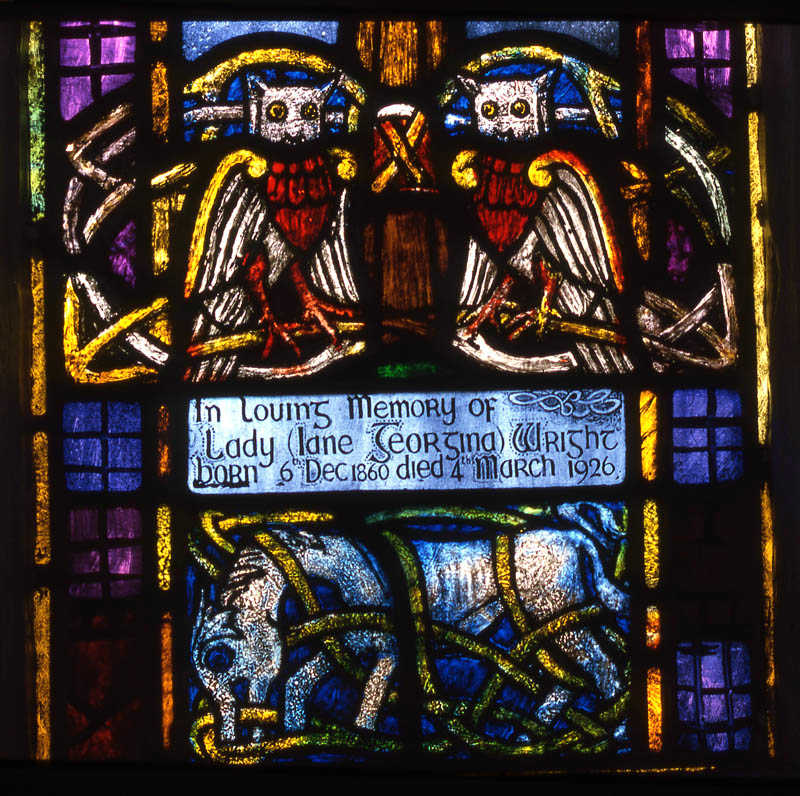

Catherine O’Brien: detail of decorative memorial window, Coolcarrigan Church, Co Kildare, 1911detail of decorative memorial window, Coolcarrigan Church, Co Kildare, 1911

Catherine O’Brien: detail of decorative memorial window, Coolcarrigan Church, Co Kildare, 1911detail of decorative memorial window, Coolcarrigan Church, Co Kildare, 1911

In January 1903, Sarah Purser launched the modest but romantically named premises, The Tower of Glass (in Gaelic An Túr Gloine), on the site of two former tennis courts in central Dublin, with Child as manager and two glaziers, one from Lowndes Drury in London and the other a former Dublin newspaper boy.

The aim was that each window should be the work of one artist who makes the sketch and cartoon and selects and paints every morsel of glass him or herself.

Coolcarrigan Church, Co Kildare.

Coolcarrigan Church, Co Kildare.

The ideal was that stained glass should be a work of free art as much as any painting or picture, and, in the absence of any known medieval Irish glass, it should emulate the intricate skill, colour and imaginative ingenuity of Celtic and medieval Irish metalwork, enamels, sculpture and manuscripts and favour Irish subject matter.

The growing interest in antiquarian research and the exciting discovery of long-buried artefacts and forgotten Irish saints in the 19th century were key factors in this.

Although Sarah Purser only designed a few small panels and very few windows (including King Cormac of Cashel (1906) in St Patrick's Cathedral, Dublin), her extensive surveys of French and English medieval glass, her important social and artistic connections, and her formidable organisational powers were crucial to the success of the venture.

It was Purser who recruited artists with the necessary aptitude to the workshop and who delegated commissions to suit their talents.

The Artists

Left: Michael Healy, detail of The Holy Women at the Tomb, Church of Ireland, Lorrha, Co Offaly, 1918. Right: Harry Clarke, St Elizabeth of Hungary, one light of a three-light window at St Mary’s, Sturminster Newton, Dorset 1921.

Left: Michael Healy, detail of The Holy Women at the Tomb, Church of Ireland, Lorrha, Co Offaly, 1918. Right: Harry Clarke, St Elizabeth of Hungary, one light of a three-light window at St Mary’s, Sturminster Newton, Dorset 1921.

An Túr Gloine’s initial commission was for what turned out to be a succession of windows over the next 40 or so years in St Brendan's Roman Catholic Cathedral in Loughrea, County Galway.

Its first recruit was Michael Healy. Originally destined for the Dominican order, his graphic flair found its lifelong vocation in his increasingly skilled, deeply coloured, scintillating stained glass.

The various stages of his artistic development can be traced in nine windows in Loughrea, from his first apprentice angel, sensitively painted under Child’s direction in 1903, to his striking Last Judgement of 1937-1940.

Like his brilliant younger Dublin contemporary, Harry Clarke, who was also trained by Alfred Child at the Metropolitan School of Art, Healy’s jewelled aciding technique imbued his grave, exquisitely painted figures with a hieratic, Byzantine splendour, while his simplified use of strong black painted lines enabled even the intriguing narrative details that are a feature of the borders of many of his windows to be clearly read from a distance.

The content ranges from mythological subjects, such as the lavishly robed, beautiful, pale featured, red-headed princesses Eithne and Fidelma, to the heavily outlined, dramatic features of the damned awaiting final judgment.

He could make glass scintillate through his etching and plating techniques, and he captured a rich range of jewelled colours, whether working on small panels such as those depicting beguiling scenes evoking the life of St Catherine to commemorate a local headmistress (1923), or St Victor (1930) in St Catherine’s and St James’s, Donore Avenue, Dublin (1923), or in full scale windows such as his final series of Dolours windows in Clongowes Wood Jesuit College Chapel, County Kildare (1936-1941).

These latter were completed by his devoted disciple and admirer, the similarly religiously inspired Evie Hone, who became a member of An Tur Gloine in 1935 and worked beside him until his death, later moving into her own converted studio in the mountains outside Dublin.

Unlike Evie Hone, whose windows need no introduction in England, Healy is little known outside Ireland, even though there are three exceptionally fine three-light windows of Healy’s in St Peter’s Church, Wallsend upon Tyne: St Patrick, St Peter and St Luke (1913); Our Lord with the Nativity and the Shepherds (1919); and Our Lord Walking on the Water (1921).

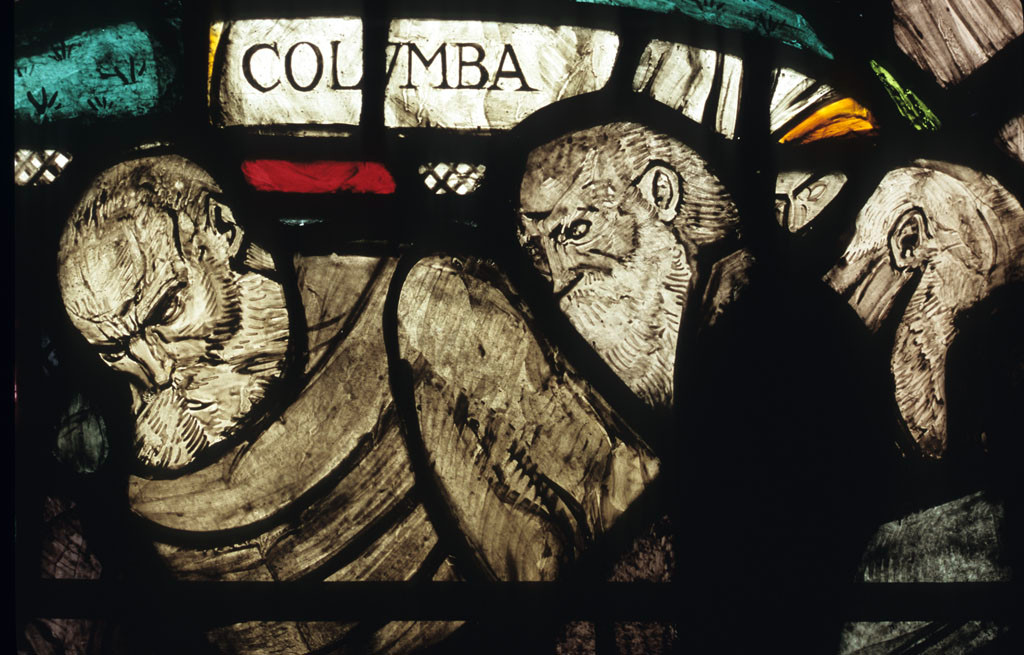

St Columba at St Cedma’s, Larne, Co Antrim, 1923

St Columba at St Cedma’s, Larne, Co Antrim, 1923

He was also responsible for completing a St Brendan window (1923) and executing a further three-light window in Holy Trinity, Bardsea, Ulverton, Lancashire.

The latter depicted the Baptism of Christ, the Crucifixion, and the Resurrection (1924), and was designed by Wilhelmina Geddes, the other artist whose work he immensely admired and emulated at An Túr Gloine.

Geddes was invited by Sarah Purser to join An Túr Gloine in 1912 from Belfast, where she had initially been trained and where she returned before leaving Ireland for good in 1925 to settle in London.

Detail of Sister Water from the Canticles window at St Michael’s, Northchapel, West Sussex (Photo: Nicholas Taylor)

Detail of Sister Water from the Canticles window at St Michael’s, Northchapel, West Sussex (Photo: Nicholas Taylor)

Her work had been spotted by the sculptress and illustrator, Beatrice Elvery, who joined the workshop in 1904 and made a number of enchanting, archetypically Arts and Crafts windows and panels using her family as models, but left for London’s Slade School of Fine Art in 1912.

A lifelong member of the studio was Catherine (Kitty) O' Brien, who had joined in 1906 and devoted her life to painting windows on all scales, using a recognisably grainy style of brushwork, richly coloured, simply painted glass, and stiffly gesturing figures of an increasingly naive character.

It was O’Brien who took over An Túr Gloine after Purser's death and she ran it until its eventual closure in January 1944. She worked alongside Ethel Rhind, who joined the studio in 1908 as a specialist in opus sectile, but, influenced by both Healy and Geddes, O' Brien worked out her own idiosyncratic style, incorporating images from nature and medieval manuscripts around her freshly conceived, colourful principal figures.

Harry Clarke; detail of St Adrian, patron saint of soldiers, Bride Street Catholic Church, Wexford, 1921

Hubert McGoldrick, who joined later, in 1920, after working with Messrs Earley in Dublin, was versatile if less prolific and evolved an effective and distinctive, if eclectic style synthesised from his older contemporaries.

The only other outstanding stained glass artist of this period, similarly trained at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art like his fellow An Túr Gloine artists, was Harry Clarke, but he worked with the ecclesiastical decorating and stained glass firm set up by his Leeds-born father Joshua Clarke in Dublin in 1886.

After his father's death in 1921, he took over the thriving family business, which he expanded and renamed Harry Clarke Stained Glass Ltd shortly before his premature death in 1931. Like Geddes, he worked from a rented studio in the Fulham Glass House in London from about 1925 but, unlike her, he did so only on a temporary basis when he needed respite from his busy Dublin studio.

Hubert McGoldrick; detail of Christ of the Sacred Heart Appearing to St Margaret Mary, St Brendan’s Cathedral, Loughrea, Co Galway, 1925

Hubert McGoldrick; detail of Christ of the Sacred Heart Appearing to St Margaret Mary, St Brendan’s Cathedral, Loughrea, Co Galway, 1925

Of the Irish artists mentioned above, it is Clarke, Hone and Geddes (all three represented in the Stained Glass Museum in the triforium of Ely Cathedral) who are best represented by their stained glass in the UK.

Clarke's work has been documented and well displayed. Hone, who only decided to work in stained glass as late as 1932, having devoted herself to the formal study and execution of abstract cubist painting for the previous 12 years, firmly established an enviable reputation with her monumental nine-light east window in Eton College Chapel (1949-52), and was commemorated with a major exhibition in London and Dublin after her death.

Like Geddes, to whom she turned to learn the techniques of stained glass, she looked to the anonymous stained glass masters of the 12th and 13th centuries for the principles of modernism in her chosen craft.

Wilhelmina Geddes; above, the main part of the war memorial window at St Bartholomew’s, Ottawa, Canada, 1919 (Photo: Jonathan Taylor

Wilhelmina Geddes; above, the main part of the war memorial window at St Bartholomew’s, Ottawa, Canada, 1919 (Photo: Jonathan Taylor

It is Geddes, unfairly overshadowed by her pupil's enviable reputation, whose achievement needs to be re-evaluated. When she died in 1955 (the same year as Hone), she was justly described by The Times as the finest stained glass artist of our time, in whose work of outstanding artistry and craftsmanship is a revival of the medieval genius

As early as 1922, when her profoundly moving, powerfully painted and sonorously coloured Crucifixion was erected in Wallsend, a future director of the National Gallery of Ireland expressed the view that she was producing the most sincerely, passionately religious stained glass of our time, while another critic praised her strong expressive drawing and her 'extraordinary power of simplifying without loss of meaning'. Others noted the religion of power and fighting, not the religion of peace and restfulness in her glass, the reat emotion in her fine, bold drawing and the virile, almost alarming strength in her superbly painted figures. Two years later, the distinguished American stained glass artist, Charles Connick, wrote of her richly complex three-light war memorial window in St Bartholomew's Church, Ottawa: 'Nowhere in modern glass is there a more striking example of a courageous adventure in the medium. This devotee of the craft stood before it recently with a feeling of personal gratitude for the spiritual beauty, the poetry and youthful audacity wrought into that goodly fabric of glass, lead and iron'. Further masterpieces can be found not only in Ireland but also in the UK: in Laleham, Surrey, Otterden, near Faversham, Kent, Northchapel in West Sussex; Egremont, on the Wirral; and Lampeter in Wales. And further afield, an exquisite example graces St Martin's Cathedral at Ypres, Belgium: a huge 89-lightTe Deum rose window made single-handedly in London by this small, deceptively frail genius of an Ulsterwoman. Nicola Gordon Bowe, David Caron, Michael Wynne, Gazetteer of Irish Stained Glass, Irish Academic Press, Dublin, 1988 Nicola Gordon Bowe, 'Wilhelmina Geddes, 1887-1955: Her Life and Work, a Reappraisal', Journal of Stained Glass, Vol XVIII, 1988 C P Curran, ‘Michael Healy: Stained Glass Worker 1873-1941’, Studies, Vol 31, March 1942 Michael Wynne, Irish Stained Glass, Eason and Son, Dublin, 1978Recommended Reading