The Traditional British Orchard

A Precious and Fragile Resource

Henry Johnson

|

|

| A traditionally grazed orchard in Conderton, Worcestershire with mistletoe and dead wood habitats, key features of traditional orchard ecosystems |

Traditional orchards have a number of features that distinguish them from similar types of land use, such as commercial orchards, and similar types of habitat, such as parkland.

Natural England (formerly English Nature) supplies the following definition:

Traditional orchards are characterised by widely spaced standard* or half-standard fruit trees, of old and often scarce varieties, grown on vigorous rootstocks* and planted at low densities, usually less than 150 trees per hectare in permanent grassland. (Words followed by asterisks are defined in the glossary below)

They will contain at least five fruit trees that have been grown as ‘standards’ and therefore have crowns high enough for livestock to graze beneath.

Apples are the most common fruit in traditional orchards, but sites usually have a mix of apple, pear, plum, damson and walnut, although rarely with all types represented. Cobnut (hazel) and cherry orchards are also a characteristic feature of certain regions.

The spacing of the trees varies according to fruit variety, with plums and cobnuts sometimes as little as 3m apart, apples 8-10m apart and cherry and perry pear orchards with spacings often over 20m. The planting pattern may be regular but successive re-plantings have often blurred any original order.

Traditional orchards are managed extensively. This means little or no use of fertilisers or herbicides beneath the trees, or chemical insecticides and fungicides among the branches. The grassland sward is either grazed (by sheep or cattle) or allowed to grow and cut for hay.

There are currently around 24,600 ha of traditional orchard in the UK, with the average size being about 1 ha.

HISTORY

The orchard has been a component of the British landscape for many centuries and has a complex history. DNA evidence strongly supports the theory that of the almost 3,000 apple varieties that populate British orchards, all are the un-hybridised descendants of the wild sweet apple Malus pumila of the Tian Shan region of Central and Inner Asia, and unrelated to the native European crab apple Malus sylvestris (1).

The Romans are traditionally credited with introducing both the sweet apple Malus pumila and the pear Pyrus communis (2) and they were competent in the skills of grafting*, developing new varieties and probably cider-making (3). Perhaps surprisingly, the 500 or so years of Roman occupation left no written evidence or vestige in a place name of such activities. The Angle, Jute and Saxon invaders who followed the Romans left a scattering of place-names, such as Applegarth (‘apple orchard’) and Appleton (‘where apples grow’), and these are thought to refer to groupings of Malus pumila established in the landscape (1).

Traditional orchard cultivation began to decline with the fall of the Roman Empire, but the associated skills and knowledge may have survived into the late medieval period within settled monastic communities. Monasteries were well suited to developing and cultivating skills such as planting, grafting and pruning in their monastic orchards or ‘pomaria’ (4). Henry VIII’s Reformation destroyed many of these orcharding centres, but his appointed fruitier Richard Harris introduced grafting material (scion wood) for pears from the Netherlands and apples from France and established orchards at Teynham in Kent.

During the 17th century much of our fruit growing expertise centred around aristocratic nurserymen such as Ralph Austen and John Tradescant, and the writer John Evelyn, who were influenced by continental, and particularly French fruit-growing heritage. These wealthy travelling plantsmen collected fruit varieties and established orchards in the estates and large houses of England. Orchards became widely associated with the aristocracy, as illustrated by the number of National Trust properties that incorporate historic orchards. Trees were often grown in quite formal arrangements on dwarfing rootstocks*, but larger trees and spacious plantings more characteristic of our idea of ‘traditional’ orchards occurred as well. By 1700, orchards were a dominant landscape feature in many counties.

The first written records of cider-making date from the reign of King John (1199-1216). By 1700 the counties of Worcestershire, Herefordshire, Gloucestershire and Somerset already had a well-established tradition of orcharding for the production of cider and perry. This industry developed to use up surplus fruit that could not be taken to market due to the region’s then inadequate infrastructure (5). These proliferating farm orchards would often have been dual purpose: providing fruit to eat, cook or store for the farm as well as juice and alcohol. Cider became a component of the farm labourer’s wage.

Many of the extant traditional orchards in Britain are the legacy of the small-scale mixed farming that was predominant before the intensification of agriculture after the second world war. As a result, these orchards are often found close to settlements and usually betray the location of former farms, now shrouded in more recent development. This proximity to habitation facilitated some of the cultural associations that are still apparent today, with orchards acting as centres for ‘songs, recipes, cider, festive gatherings... wisdom gathered over generations about pruning and grafting, aspect and slope, soil and season, variety and use’ (6). The wassail is one such example of these ‘festive gatherings’ designed to ward off evil spirits and encourage productive cropping in the coming year. It still occurs at Carhampton in Somerset and in many other parts of the West Country.

|

|

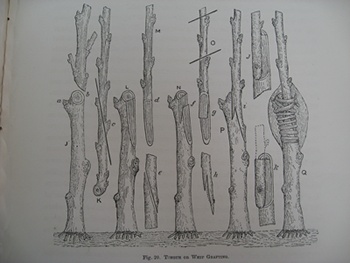

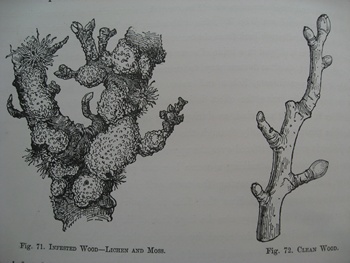

| Two illustrations from John Wright’s The Fruit Grower’s Guide published in 1892, at a time when Victorian horticulturalists were devoting tremendous energy to the study of all aspects of fruit growing | |

In contrast to cider orchards, perry pear orchards with standard trees are a rarer but more spectacular component of the landscape of south-west England, with the trees growing larger and older than apple trees. Some of the old perry pear trees that survive today date from 18th century plantings, in keeping with the saying, ‘Walnuts and pears, you plant for your heirs’. Luckwill and Pollard list 101 different varieties of perry pear from Gloucestershire alone, many being very localised.

The 19th century was a turbulent period for traditional orchards, but by 1870 fruit growing was on the increase again to provide for nascent markets (such as that for jam) supplied by a new rail network. From 1912 onwards, the standardised rootstocks developed by the research stations at East Malling, Merton and Long Ashton enabled people to maximise their planting arrangements for productivity, with the vigorous type M25 rootstock the most suitable for grazed traditional orchards.

Since 1950, fewer and fewer traditional orchards have been planted and the national stock of standard fruit trees is now heavily biased towards an older generation of trees that are more than 50 years old. The 1980s saw the beginning of a significant push to try to reduce the national dependence on food imports with the advent of the Common Agricultural Policy. Funding was made available to convert traditional orchards into more productive farmland causing the widespread destruction of older orchards; a pattern which, to some extent, continues today. Over the last century virtually all fruit grown for the consumer market has been produced in intensive commercial orchards that utilise semi-dwarfing rootstocks, a range of chemical treatments and trees planted closely in rows along herbicide treated strips. Traditional standard orchards are still planted in association with the cider industry, since sheep-grazed orchards are a component of the commercial set-up of a few producers, like Julian Temperley at Burrow Hill, Somerset.

BIODIVERSITY

The ecological value of traditional orchards has long been underestimated and they have only recently come to be appreciated as biodiverse islands within a largely intensive agricultural landscape. In 2004, over 1,800 species were found across the plant, fungi and animal kingdoms in just 2.2 ha of traditional orchard in the Wyre Valley Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in Worcestershire in the first study of its kind in the UK (7). In April 2009, Natural England published a report on traditional orchard biodiversity after surveying six traditional orchards for diversity of species and habitat features, with a particular focus on bryophytes*, lichens, invertebrates and fungi. Within these groups they found a total of 810 species, and more generally the sites were rich in nationally rare and scarce species and contained a varied matrix of different habitats including veteran fruit trees, non-fruit trees, hedgerows, scrub, grassland communities, dead wood, ponds and streams.

Fruit trees age much more quickly than most other species found in the countryside so they rapidly accumulate the 'veteran' features associated with over-mature trees. Large volumes of standing dead wood in the form of ‘stag’s heads’, whole limbs and rotting heartwood are specific habitats favoured by suites of very specialised organisms that have become increasingly rare in the countryside. The presence of old trees spaced within permanent grassland creates a range of habitats very similar to those found in wood pasture landscapes (such as medieval hunting parks like Staverton Park in Suffolk).

The sward communities that inhabit the permanent grassland beneath the trees can be rich and varied, with vegetation groups associated with semi-natural (but rarely completely ‘un-improved’*) grasslands. Traditional orchards are a stronghold for the regionalised populations of the hemi-parasite mistletoe (Viscum album). This has six invertebrate species entirely dependent on its presence to complete their life cycle, and as a result all six species have declined through loss of old orchard habitat, including the mistletoe marble moth (Celypha woodiana), a UK Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) ‘priority’ species.

The abundance of insects and fruit in a traditional orchard supports varied mammal and bird populations including specialist species such as the lesser spotted woodpecker, bullfinch and flycatchers. Different orchards can be home to different specialised communities, such as lichens and wood-inhabiting beetles, which require a continuity of habitat over time and a network of these sites is therefore critical in sustaining populations across large areas. In recognition of this, traditional orchards were awarded a BAP ‘priority’ habitat status by Natural England in August 2007, under the UK Biodiversity Partnership.

MANAGING A TRADITIONAL ORCHARD

Any traditional orchard to be managed or restored should be treated sensitively: it is an increasingly rare environment in Britain and one that is not easily or quickly re-created. First, make an assessment of the orchard’s condition, its contents and history. Consider historical records and available local knowledge to gauge the age of the site, the reasons for its initial planting and its subsequent use. Decide what you want to achieve with the management regime. Do you want to restore a site to its former extent or diversify with new varieties? Do you plan to cook, juice or ferment the crop, or is it purely a space for leisure and wildlife?

|

|||

| Pruning can be very laborious, especially if the trees are very large. Community orchard projects are a great way of mobilising volunteers and transforming the work into a social occasion. | |||

|

|

||

| Above left: Autumn is the season when orchards really come into their own, and picking fruit to make juice or cider is another great way of involving people. Above right: Pruning fruit trees in the winter is a way of encouraging reactive growth, more fruit and better tree and fruit health. With very old trees that have not been pruned regularly in the past, do not remove too much material in one go as this may stress the tree or even kill it. Spread the work over two or three years to reduce these risks. Also bear in mind that trees which have hardly ever been pruned may well be perfectly healthy and productive if left untouched. | |||

Before any work is undertaken, take some time to observe the orchard’s natural habitats. Traditional orchards are used by a diverse range of organisms with some, such as migratory thrushes, only itinerant autumn and early winter visitors. Rotten limbs and other dead wood features should be left to gradually mature unless badly diseased or of immediate danger to people.

Managing the grass beneath the trees is important. An effective grazing regime will reduce the maintenance requirements of a site and can greatly improve the health of the trees and the quality of many habitats. If the sward is species-rich and contains wildflowers and grasses that you wish to encourage, allowing a period for these plants to flower and set seed may be beneficial. Sheep can rapidly develop a taste for bark and will ring-bark trees and kill them unless the trees are protected or the animals are closely monitored. Cattle can be even more destructive and substantial tree guards will be needed to stop them leaning on younger trees and breaking them.

If mistletoe is present, it should be managed to prevent it from swamping the trees, with both berry-carrying female and berry-less male plants pruned periodically. Try to get fruit trees identified and graft anything rare or unusual onto new rootstocks for the next generation of trees.

Traditional orchards are eligible for funding under the Higher Level component of Natural England’s Environmental Stewardship scheme for landowners, providing money to those eligible to offset costs for restoring or creating traditional orchards. Grants from local councils, government-sponsored programmes and industry schemes like Biffaward may also be available.

Natural England has produced a series of technical information notes providing advice on the management and maintenance of traditional orchards which can be downloaded from its website. These include several specifically about formative, maintenance and restorative pruning that are essential reading for the uninitiated.

THE ORCHARD CONSERVATION MOVEMENT

For the past 50 years the acreage of traditional orchards has been steadily decreasing, with an estimated loss in area of 60 per cent nationally since 1950, and with some counties, such as Devon, seeing losses of up to 90 per cent. Agricultural intensification is the single greatest cause. For commercial growers, traditional orchards have long been economically unsustainable since large trees require a lot of labour to harvest from and prune and are less productive per-hectare than bush trees.

Small traditional orchards are often found in or near villages and towns, and this has left them highly vulnerable to development. An orchard identified on maps as dating back to 1575 was replaced in 2007 by housing in the village of Bawdrip on the Somerset Levels despite a decade of campaigning from local people. More recently, in the town of Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire plans to replace an ancient orchard with a car park have polarised local opinion. Orchard sites are currently classified as ‘agricultural land’ and so have only limited legal protection from such schemes.

Generally, traditional orchards are poorly represented among SSSI, National Nature Reserve or Wildlife Trust sites. There are a few notable exceptions such as Lower House Farm, a Herefordshire Wildlife Trust reserve and the Wyre Forest SSSI in Worcestershire.

Charities and non-governmental organisations have played a primary role in mobilising a traditional orchard conservation movement to address these threats. Common Ground was an early pioneer, establishing the Apple Day celebration in 1990, which has steadily accumulated interest and is now a nationwide event. Currently there are orchard groups representing most of Britain, with the common aim of promoting traditional orchard heritage and knowledge. There are also many community orchard projects in the UK that involve groups of local volunteers in the restoration, preservation or creation of orchards. The orchards of Cleeve Prior in Worcestershire were acquired and restored by a locally established heritage trust, with the fruit used to make Prior’s Tipple, a cider that promotes the use of old orchards.

Despite this movement, traditional orchards are still severely under-protected by the law and conflicts between developers, farmers and conservationists regularly occur. Protection measures for threatened sites involve the establishment of Tree Protection Orders (TPOs) through local council tree officers, combined with building a case around the ecological, genetic, historical and social importance of the site. A case study for a successful campaign is the perry pear orchard near Brockworth, Gloucestershire. Information about the campaign is available on the Gloucestershire Orchard Group website.

Flagship species have been used by various conservation groups to publicise traditional orchard conservation with, for example, Butterfly Conservation concerned about declines in the mistletoe marble moth. The People’s Trust for Endangered Species recently undertook a national survey of traditional orchard extent and condition, with the noble chafer beetle as focus species.

In October 2008 the National Trust and Natural England committed £536,000 to establishing a partnership project titled ‘Conserving and restoring traditional orchards in England’, which has funded restoration work, the creation of new orchards, and surveying and training activities. It is set to continue until March 2011.

~~~

Notes

1 Juniper and Mabberley, 2006

2 Loudon, 1844

3 French, 1982

4 Russell, 2007

5 Roach, 1985

6 Clifford and King, 2007

7 Smart and Winnall, 2006

Recommended Reading

S Clifford and A King, The Apple Source Book,

Hodder and Stoughton, London, 2007

RK French, The History and Virtues of Cyder,

Robert Hale Ltd, London, 1982

BE Juniper and DJ Mabberley, The

Story of the Apple, Timber Press Inc,

Portland, Oregon, USA, 2006

JC Loudon, Arboretum et Fructicetum

Britannicum, Longman, Brown, Green,

and Longmans, London, 1844

LC Luckwill and A Pollard, Perry Pears, the

National Fruit and Cider Institute and

the University of Bristol,

Bristol, 1963

M Lush et al, ‘Biodiversity studies

of six traditional orchards in

England’, Natural England Research

Reports,

No 025, 2009

FA Roach, Cultivated Fruits of Britain,

Blackwell, Oxford, 1985

J Russell, Man-made Eden: Historic Orchards

in Somerset and Gloucestershire,

Redcliffe Press Ltd, Bristol, 2007

MJ Smart and RA Winnall (eds), ‘The

biodiversity of three traditional

orchards within the Wyre Forest SSSI

in Worcester-shire: a survey by the

Wyre Forest Study Group’, English

Nature Research Reports, No 707, 2006

C Wedge, ‘Traditional Orchards: A

Summary’, Natural England Technical

Information Notes, No 012, 2007

Useful Websites

Biffaward www.biffaward.org

Charingworth Orchard Trust www.charingworthorchardtrust.blogspot.com

Common Ground www.commonground.org.uk

Gloucestershire Orchard Group www.gloucestershireorchardgroup.org.uk

Natural England www.naturalengland.org.uk

Orchard Network www.orchardnetwork.org.uk

People’s Trust for Endangered Species www.ptes.org

GLOSSARY |

|

Bryophytes |

spore-producing non-vascular land plants that include the mosses, liverworts and hornworts |

Dwarfing rootstock |

non-vigorous root system used to ensure the trees resulting from grafting stay small (1-3m tall at maturity) and are therefore easier to manage |

Grafting |

method of vegetative propagation where tissue from one plant (a scion) is attached to the root system of another plant (a rootstock, usually of the same species) in order to replicate the variety of the scion. The tissues of the two parts then grow together producing one tree that is genetically two different plants |

Improved pasture |

semi-natural grassland that has had fertilizer and/or herbicides applied to it to increase yields resulting in reduced sward diversity |

Standard tree |

tree grown on a vigorous rootstock that has a crown high enough to allow animals to graze beneath without them reaching the branches |

Vigorous rootstock |

root system used to ensure the trees resulting from grafting grow into half-standards or standards (3-10m tall at maturity) |