Wallpapers in the Historic Interior

Allyson McDermott

|

|

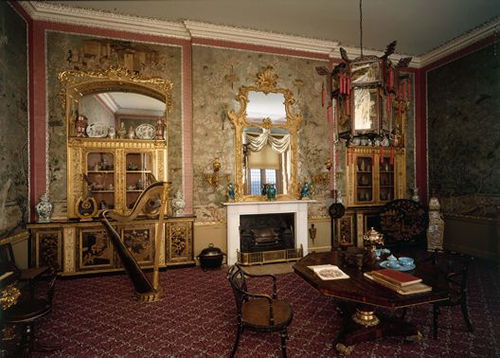

| A 19th century Chinese paper at Temple Newsam House, Leeds |

Remarkably, many original wallpaper examples survive in situ in reasonable condition but even in fragmentary form they can still provide a unique archaeological record of change and development within an historic interior.

Wallpapers reflect the fashionable trends of the period and the status, history and personal taste of the occupants. They give an indication of the hierarchical function of rooms within the house and often record special events. The reward for the returning prodigal in Fathers and Sons was a horse and some ‘new bedroom wallpaper’, and recent research indicates that The Dutch House, Kew was extensively redecorated for the arrival of ‘Mad’ King George using bright, fresh, green verditer paper.

Papers were not always stripped prior to re decoration, particularly where they still provided a firm support. Sandwiches of 20-30 layers are not unusual and can provide a valuable record of the decoration and use of building. Arguably, any wallpapers discovered could be significant and are worth investigating. Even where stripped, there is often enough residual evidence to identify, understand and re-create an original scheme. Careful examination of pigment particles, printing methods, paper fibres and even the hanging and preparation techniques can provide vital information.

Experience has proved that specialist investigation into both architectural paint and wallpaper should be carried out before work begins and before any intervention destroys valuable evidence. This research may then provide the basis of a sound understanding which will inform both the client and their professional advisors and ensure a considered approach to any project.

WALLPAPER IN THE 17th AND 18th CENTURIESWallpapers have always reflected the fashionable aspirations of their owners, imitating more expensive materials such as silk damask, stucco, epic wall paintings, wood and marbling. The earliest papers seem to have been multi-purpose as they have been found lining deed boxes and harpsichords as well as decorating walls. These have small scale repeating floral or heraldic designs, block printed in carbon black onto single sheets of rag paper, which could then be applied in modular fashion.

Although the tradition of using single sheet designs continued in France, in England, fashion dictated an increase in the size and sophistication of designs, which required ever larger and/or multiple blocks. Several formal flock papers dating from 1830-40 were copies of popular silk damask designs which had designs measuring over seven feet.

|

|

| A detail of an ‘India’ paper, c1751 |

Larger patterns required that paper be joined to form a roll. Once joined and sized with animal glue, the ground colour would be applied using broad strokes, working the colour with a circular brush. This usually comprised a chalk base and strong-hued pigment bound with animal glue. The chalk provided a smooth dense and opaque layer, and served to disguise the joins and provide an even layer for printing. The pigment was often an organic dyestuff such as indigo, red madder or, in more costly papers, carmine. These had high tinting strength when first applied, but faded rapidly when exposed to bright light; consequently few of these papers appear now as they were originally intended.

In the earlier papers, the black printed outline was often embellished by applying colour freehand with a brush or through a stencil cut from leather. Although this technique continued to be used throughout the 18th century (it was cheaper to make a stencil than to carve a block), it was generally enhanced by, or replaced with, block printed colour. Colours were usually the cheaper, easily available earth colours such as yellow ochre or terre verte (green), although more expensive synthesised colours such as Prussian blue (greeny blue) and verditer (usually blue) were popular for the highly fashionable flock wallpapers known as ‘damasks’.

Flock wallpapers were produced by printing a design in a pigmented adhesive, then sprinkling with chopped wool or silk. The richness and durability of these papers made them both fashionable and popular amongst the aristocracy, and many larger houses could boast several rooms decorated in this way. However, flock wallpapers were heavy and because of their varnished grounds, were difficult to hang. They were usually applied onto walls prepared with stretched linen canvas and embellished with a coordinating border to disguise rough edges and rusting tack heads.

Hand-painted Chinese export papers seem to have developed in response to the fashion for all forms of Chinoiserie. Although there are references to Japanese, Chinese or ‘India paper’ in the late 17th and early 18th century, the earliest examples of ‘wallpapers’ survive at Fellbrigg, Norfolk and Dalemain in Cumbria and date from the 1750s. These have exotic bird and flower designs, painted with considerable accuracy and expertise, and their colours were almost jewel-like in their brilliance and shimmering delicacy. The effect was achieved by a complex combination of rare pigments and glazes. Many of these papers were specially ordered by the client for a specific interior, perhaps to act as a backdrop to treasured collections of oriental artefacts. Others were supplied by society decorators such as Thomas Bromwich and installed at considerable expense.

Papers depicting extraordinarily detailed ‘Scenes from Chinese Life’ dating from 1760s and ‘70s survive at Blickling, Norfolk, Harewood House, Yorkshire and Saltram, Devon.

The popularity of these papers continued until the early 19th Century when Chinoiserie had a second flowering, inspired by the exoticism of the Royal Pavilion at Brighton. These later papers, whilst still highly decorative, lack the subtlety of their predecessors.

|

|

| An imitation leather paper, c1890, embossed with metal foil. | |

|

|

| A William Morris hand-blocked fruit wallpaper used on a ceiling |

By the end of the 18th century, imported French papers were gaining ground. The Rococo exuberance of Reveillon led the trend, followed in the early 19th century by the sumptuous ‘paysage’ papers of Dufour Leroy and Zuber.

These extravagant panoramas, using several thousand sequential blocks, depicted epic scenes such as the voyages of Captain Cook, or the history of Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt, and were sold for their educational as well as their decorative qualities. Several of these papers are still produced today and many earlier examples survive in situ.

Generally, increasing demand led to a proliferation of designs and ever more sophisticated techniques of manufacture such as double flocking, highlights of gold and silver dust and satin effect grounds. Despite the ideals of William Morris who supported the traditional craft techniques of hand printing, it was this very mechanisation that made wallpapers widely accessible to a growing market. This culminated in the embossed ‘Japanese leather paper’, Lincrusta, Anaglypta and the multifarious Tynecastle ‘tapestries’ made from paper, canvas or indeed virtually any material that would give a good effect. Every middle class home could become a Jacobean manor and every newly built Scottish castle a venerable baronial hall.

COMMISSIONING CONSERVATIONInvestigation

and recording

Surprisingly,

for such an apparently ephemeral material, many original examples of historic

wallpaper still survive. These are usually spectacular examples of Chinese

export paper or French panoramas which play an important decorative role

within the interior and which have always been appreciated and maintained.

Durable flock, Lincrusta and Anaglypta papers survive almost by default

whilst others may relate to a particular occupancy such as Churchill’s

simple 20th century papers at Chartwell in Kent. These original papers

may already be protected but the preliminary investigation should establish

any historical significance even if this is not immediately obvious.

The

condition survey

Recording:

papers should be comprehensively photographed, documented and any additional

historical evidence noted and retained.

Assessment of condition: this may require some environmental monitoring to help identify reasons for deterioration and to indicate any improvements that may be necessary.

Recommendations for treatment: this may offer several options, which will be dictated by location and future use as well as environmental conditions and the nature and condition of the materials used.

Conservation

Paper

is hygroscopic (it attracts and absorbs moisture) and it is therefore

particularly vulnerable in moist conditions. It will also absorb potentially

acidic atmospheric pollutants. Historically, this may have included

smoke from fires, cigars, candles and gasoliers, and latterly, fumes

from industry and the internal combustion engine. Glues, wood pulp containing

papers and certain pigments may also contain acidic contaminants. Conversely,

excess alkalinity, usually from damp plaster walls, can also cause problems.

|

|

| James Caverhill printing a reproduction of a red flock paper which was damaged in the fire at Uppark. | |

|

|

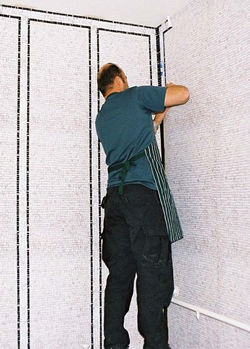

| Adrian McDermott hanging a digitally reproduced paper at Derngate, Northampton. |

In

situ conservation

If the

wallpaper and its wall face substrate are sound, simple remedial treatments

can be carried out in situ. This is only appropriate if the paper is

in sound condition and well attached to the wall. Treatment may include

surface cleaning, consolidation of any flaking pigment and simple repairs

to small areas of damage. All conservation treatments must be reversible,

should work effectively and leave no potentially harmful residues.

Removal

and conservation

If a canvas lining

has deteriorated and is putting the paper at risk, removal and full

conservation should be considered. Removal may also be necessary if

there are structural problems or if electrical work is to be carried

out. Removal may be the preferred option if the paper itself deteriorating

due to high levels of acidity.

Once carefully removed from the walls, treatment should be carried out in a conservation studio. After extensive testing, this will usually involve separation of the constituent layers, surface cleaning, consolidation, reduction or neutralisation of acidity, repair and possibly relining. Sympathetic, reversible conservation-quality materials and suitably trained conservators should be used throughout.

Rehanging conserved paperWhen re-hanging the conserved paper, there are several approaches:

- using methods and materials as close to original as possible

- using a modern textile liner

- mounting onto battens or panels.

Each of these approaches has some merit, but it is perhaps the first option that is most appropriate for the historic interior. Whether this involves applying the paper to stretched, lined canvas or directly to the plastered wall, both methods can be adapted slightly to ensure longevity without compromising historical integrity. The conservator should also provide a manual for the future care and protection of wallpaper. It may also be helpful to arrange annual inspection.

Preserving fragments

If the paper only survives in fragmentary form, or is in very poor condition, display may not be possible, and the use of the building may dictate a less fragile finish. If the original paper is removed and stored, there is always danger that it will become disassociated from historical context, therefore:

-

investigate, record and preserve the original in situ

-

commission an accurate reproduction on basis of the evidence

-

protect the original before hanging the new paper by lining with conservation grade Japanese paper or battening out with stretched and acid-free lining paper.

Alternatively, the original can be revealed and sympathetically incorporated into the new scheme. This approach also works after conservation, where fire or flood has caused significant loss.

COMMISSIONING RECONSTRUCTIONInvestigation

and analysis

A

reproduction can be commissioned once the pattern, the materials and

the methods of manufacture have been identified.

The most effective reconstruction is one which has the same quality and surface texture of the original. For those with a limited budget, certain designs may be available commercially but, by comparison, this is clearly a less satisfactory option.

Origination,

artwork and printing

Some preliminary

research and experimentation may be necessary to re-learn original techniques,

but this can be an interesting and even exciting process enabling the

reconstruction of rich and accurate facsimiles of many types of wallpapers.

Block printing using carved blocks and distemper colours is always a

delight. Flock wallpaper is rather messy but equally effective. Embossed

papers can by reproduced by hand with some difficulty but at Kinlochmoidart

House in Scotland this has proved successful. Machine-printed papers

have always posed a problem as it is not economically viable to re-commission

large scale machinery for a limited run. Recent developments in digital

imaging using the original type of paper stock seem an effective solution,

and this technique was recently used at the Rennie Mackintosh House

in Derngate, Northampton.

Recommended Reading

-

C Rowell and JM Robinson, Uppark Restored, The National Trust, London, 1996

-

C Oman and J Hamilton, Wallpapers, Sotheby in association with the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, 1982

-

R Dossie, The Handmaid to the Arts, 2nd edition, J Nourse, London, 1764

-

L Hoskins (ed), The Papered Wall, Thames and Hudson, London, 1994

-

G Saunders, Wallpaper in Interior Decoration, V&A Publications, London, 2002

WALLPAPER COLLECTIONS

- The Victoria & Albert Museum, London

- Temple Newsam House, Leeds

- The Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester

- The Public Record Office, Kew