The Conservation and Thermal Improvement of Timber Windows

The need to conserve the natural environment by reducing heat loss presents architectural conservationists and home owners with an ethical dilemma where historic windows are concerned. Jonathan Taylor outlines the need for sympathetic solutions.

|

|

| Plastic replacement windows in a house in South London. The windows fail to match the fine details of the originals, or the appearance of painted timber. |

Energy used to heat and construct buildings accounts for over 50 per cent of all energy consumed in the United Kingdom (transport consumes the bulk of the remainder). The by-product of producing that energy is carbon dioxide and sulphur dioxide emissions from power stations, contributing to global warming and acid rain. As a result, the Government is now committed to stabilising CO² emissions by the year 2000. The issues need to be considered by all involved in the design, construction and maintenance of buildings, not only as a statutory requirement of the Building Regulations, but also because additional requirements may be imposed by building owners including housing associations in particular, and by local authority 'home improvement' grants.

However, the effect of some improvements can be extremely damaging to an historic building or place. Double glazing in particular may involve the loss of the original windows and the introduction of a range of details which can ruin the appearance of the building.

Where a building is listed, all alterations which affect its character can be controlled, and strict controls (Article IV Directions) may also be imposed by local authorities on specific alterations to buildings within conservation areas which they might otherwise be unable to control.

STATUTORY REQUIREMENTS FOR ENERGY CONSERVATION

All development is regulated under the Building Regulations. Part L 'The Conservation of Fuel and Power' (or Part J of the Scottish Building Regulations) applies strict limitations on the heat loss permissible from new buildings, from extensions where the floor area proposed exceeds 10m², and in some cases from existing buildings affected by alterations. In an existing building it is usually only the components being altered which are affected by the Regulations. However where a building is being converted to flats or from non-residential to residential and for certain other changes of use, they can apply to the whole building. Residential conversions will be required to achieve an energy rating which satisfies a 'Standard Assessment Procedure'. Part L (or J) does not apply to buildings and extensions which are not habitable. A conservatory for example, may not need to comply if it is separated from the interior of the building by doors or if it is under 10m².

The insulation standards, which are measured in units of thermal transmittance or 'U-value', favour double rather than single glazing, but there is a considerable degree of flexibility, and Part L specifically states that double glazing 'could be inappropriate in conservation work'. Acceptable standards are given by the ratio of window opening to floor area for single as well as double glazing, and variation from standards are also acceptable 'if compensatory provisions are made'; increases in insulation to the roof space for example, could be used to off-set the heat lost through single glazing; solar gain through south-facing windows may also be taken into account.

It is interesting to note that aluminium and PVCu does not perform as well as timber in terms of their thermal efficiency. In addition both involve a much greater consumption of energy in their production than is used to produce timber - over 45 times as much in the case of aluminium (TRADA figures). Wood, as a natural renewable resource, is clearly preferable to any man-made alternative.

MAKING SENSITIVE IMPROVEMENTS

For older buildings and for listed buildings in particular, where it is essential to improve the thermal efficiency of the existing windows, the least obtrusive option is to introduce draught proofing measures. For casement windows the process is simple, with a wide range of products available, including durable rubber seals which are discretely rebated into the window frame. The draught proofing of double hung sash windows is more complex, requiring the replacement of the parting bead with a new component incorporating rubber blades to maintain the seal at the sides, and compression seals to the meeting rail, window head and sill. These seals may be purchased for installation by a joiner, or alternately there are companies included in the Building Conservation Directory which specialise in overhauling, repairing and draught-proofing sash windows. Thorough treatment using purpose-made fittings has the added benefit of making the sashes slide more easily and stops them from rattling with every gust of wind.

Secondary glazing also provides an alternative where the exterior of an historic building needs to be protected, although the double reflection caused by the second pane of glass can be seen externally. This approach may be unacceptable internally, as the effect of even the most sensitively designed secondary glazing on the character of the windows from the inside can be excessive, and they cannot be used where there are shutters on the inside.

In the 19th century some houses were constructed using secondary glazing in the form of a second pair of sash windows which drop down together into a pocket below the window, covered by a hinged extension of the window cill, and fronted by an attractively moulded panel. Although rarely used today, this approach provides an interesting solution where there are no shutters to obstruct. Metal-framed vertical sliding sashes are commonly used, which fit tight against the window. The small, simple sections are not too obtrusive during daylight hours, when they are seen against the light, but at night they can be glaringly obvious as an entirely alien element in a fine interior.

A cheap and simple method of secondary glazing is to fit a single frame of glass over the whole window within the reveal which can be removed and stored in the summer. The only limitation on this system is the size of glass which can be handled easily without breakage, and it is really only suitable for small windows and windows divided into smaller lights by mullions and transoms.

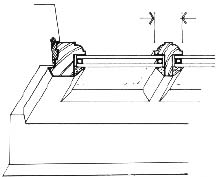

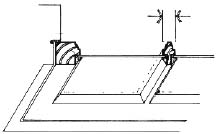

Secondary glazing allows the originals to be retained and is generally accepted by planning authorities for use in listed buildings. Double glazing on the other hand can rarely be added to existing windows without major modification due to the need for thicker glazing bars to hide the spacer bars (see diagram), the additional thickness of the sealed units and the additional weight of glass on fine timber members.

REPLACEMENT WINDOWS

|

||

| Modern purpose-made casement detail: The use of a double rebate to prevent draughts makes the casement sit proud of the frame. The wide glazing bar is necessary to hide the spacer used to separate the two panes of the sealed unit. These are commonly up to 44mm thick | ||

|

||

| Typical mid-19th century casement detail:The single rebate construction and the narrow glazing bar produce finer details. Sills were usually of stone or render, as the near horizontal surface inevitably collects water and decays rapidly |

Where a building is listed, planning authorities usually require existing windows to be retained and repaired where possible, unless they are clearly falling to bits and cannot be repaired, or are later additions which are obviously the wrong design for the building. A fine antique piece of furniture is prized not only for its completeness but also for its imperfections, and so may a window; early glass may display the radiating ripples and tiny air bubbles indicating that it was hand blown; and sash windows in particular are highly intricate and sophisticated pieces of furniture, superbly constructed to last, and deserving careful restoration.

Listed protection applies to every part of a building, and consent is required for the alteration as well as the removal of its windows. Their replacement by new, double glazed windows will usually be resisted for two reasons; the loss of original fabric and the change in character and detail.

There is more flexibility for introducing double glazing in unlisted buildings within a conservation area, as the emphasis of control is on protecting the external appearance of a building and the affect of alterations on the character of the area. However, here too the need to retain glazing bars presents almost insurmountable problems, as the 20mm width of a typical glazing bar is too narrow to hide the spacing bar of a sealed unit. One solution is to incorporate dummy timber glazing bars which follow the original profile and pattern exactly, but are 'planted' onto the inner and outer faces and do not run through.

Double glazed windows have also been produced with smaller spacer bars and the glazing bars have been whittled down to the bare minimum. In this way it is possible to produce a 25mm wide glazing bar which works. In a large window with a single glazing bar, the difference will not be as noticeable as in a small-paned sash.

Outside conservation areas alterations to windows cannot be controlled. The use of replacement PVCu and aluminium is on the decline in many areas as people become increasingly aware of their disadvantages in design and performance, and their negative effect on house value. More sensitive solutions in timber, including double glazed examples, undoubtedly provide a less damaging solution which are broadly welcomed.

VENTILATION

Where new thermally efficient windows, secondary glazing or draught-proof seals are introduced, the loss of ventilation around the old frames may promote condensation problems and damp within the building. Sources of damp include kitchens and bathrooms, breath, building materials such as drying plaster, and solid external walls and floors. In a properly ventilated building, damp may never be seen as a problem. Seal the windows and doors however, and the humidity level can rapidly escalate to the point where painted finishes on external walls begin to flake, mildew appears in bathrooms and kitchens in particular, and at around 20 to 30 per cent the risk of timber decay increases substantially. The controlled ventilation of the whole building must be considered, taking into account the supply of fresh air from outside, at a low level, passing through the building to exit ideally through the chimney stacks and under the eaves without the need for visible ventilators and avoiding draughts. Particular attention should be paid to under-floor spaces, ground floor rooms and bathrooms. Heat exchangers can also be used to recover much of the heat lost in this manner as part of a comprehensive approach to thermal efficiency.

If carried out with care and consideration, it is possible to improve the thermal efficiency of buildings with minimal impact on their appearance and historic interest through the use of a wide variety of measures. Although there will be exceptional cases where it is possible to introduce double glazing into historic buildings, and greater opportunity in conservation areas, it should be remembered that this is just one of a number of methods of improving the thermal efficiency of buildings.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- David Wrightson, 'Mandatory Double Glazing: Heat Loss Versus Heritage', Article in Context, issues 45 and 46, Association of Conservation Officers, (www.ihbc.org.uk) London, 1995

- Framing Opinions, Supplement to Conservation Bulletin, English Heritage, London, 1991

- National Trust for Historic Preservation, Repairing Old and Historic Windows. The Preservation Press, Washington DC, 1992

- Harry Munn, Joinery for Repair and Restoration Contracts, Attic Books, Builth Wells, Powys, 1989