T W E N T Y T H I R D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 6

1 0 9

3.3

STRUCTURE & FABR I C :

ME TAL ,

WOOD & GLASS

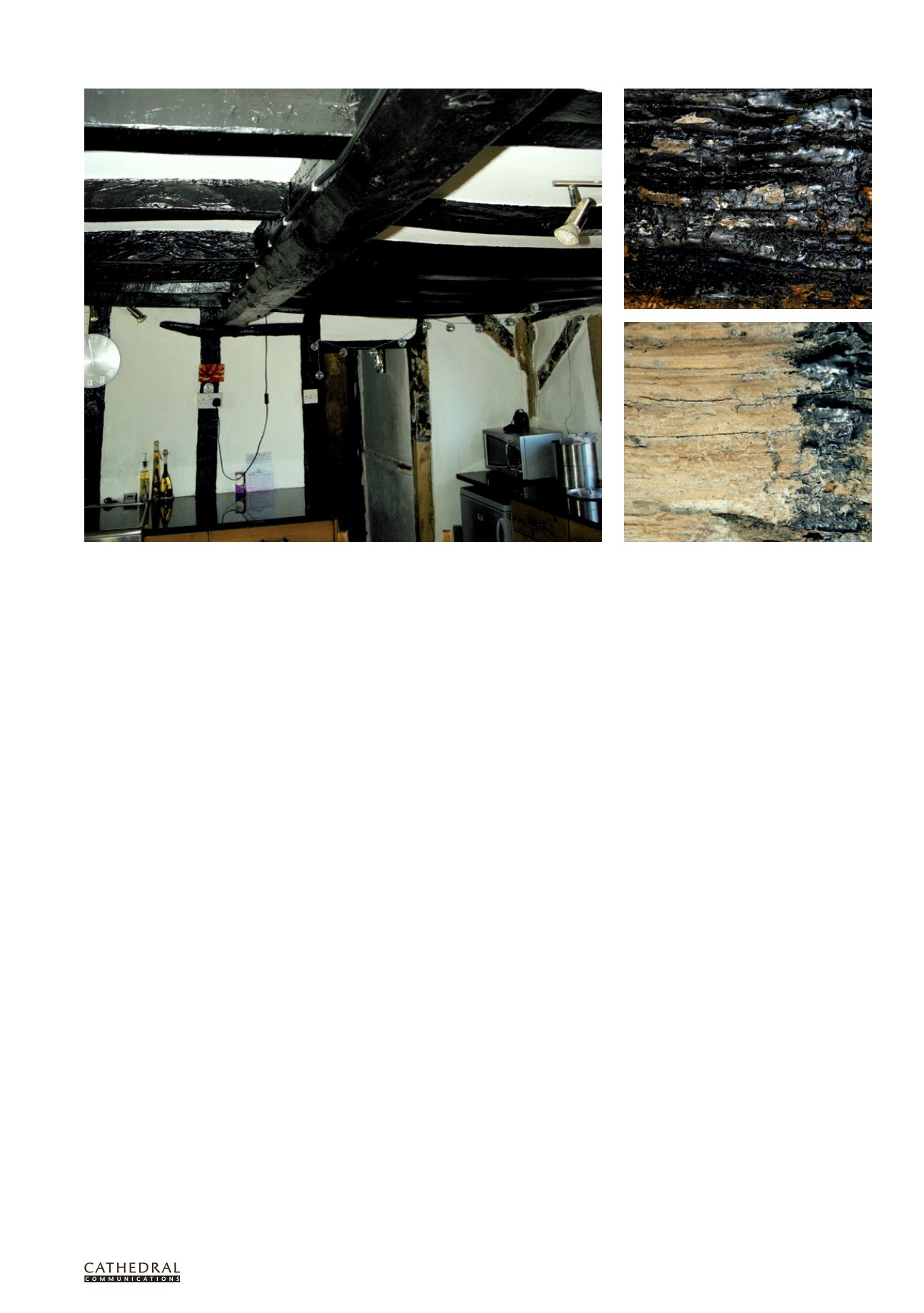

a 19th-century fashion, possibly inspired by

earlier precedents, and that the liquids from

coal and tar deposits were used. However,

closer inspection often shows that the paint

is more modern black gloss. This can give the

timber a dated appearance that seems out

of character with the softer palettes of other

materials in the building.

There is now an increasing desire to

remove this paint to reveal the original timber,

typically internally but sometimes externally

too. This is often a welcome change which

allows the original timber to be seen and it

can dramatically change the character of

the building. It does, however, bring with it a

number of issues and challenges.

The surface of the timber may contain

archaeological evidence of the building’s

construction and development such as

carpenters’ marks, tool marks, ritual marks

and early decorative finishes, often obscured

by many layers of paint.

Even where no archaeological features

exist, the aesthetic value of the surface

should also be considered. The patina and the

presence of a cohesive and unaltered surface

have a value that is easily lost if care is not

taken. Over-aggressive cleaning can cause

irreversible damage to the timber’s surface and

discolouration from chemical cleaning agents

can be difficult to remove without risking

further damage.

The type of wood (hardwood or

softwood), species, rate of growth, type

of conversion and quantity of sapwood

all determine the characteristics of the

timber’s surface and how it will respond

to the various paint removal methods.

If the decision is taken to remove paint,

it is vital that the chosen method ensures

maximum retention of the underlying surface.

PAINT REMOVAL METHODS

Paint removal methods fall into two main

groups: air abrasive and chemical. These are

explored in more detail below.

If the building is listed, the removal

of paint will always require listed building

consent because it changes the character of

the building. There are many horror stories

about poor attempts at paint removal by so-

called specialists which have led to serious

and irreversible damage to the timber. It is a

process that requires careful consideration

and every job will require a different approach.

The nature of the paint and the underlying

substrate should all be taken into account

before choosing a suitable method.

Many conservation officers will resist

any sort of abrasive method (especially

sandblasting) while others will consider

it when presented with a detailed method

statement prepared by a conservation

specialist, and provided the work is carried out

by an experienced contractor. A sample panel

is often required before works can commence.

There is a third option which is becoming

quite popular: repainting the timber to look

like original timber. A few companies offer

this service and wood graining can look quite

convincing. The arguments for and against over

painting are too involved to be explored here

but it is worth noting that this option exists.

AIR ABRASIVE METHODS

Dry abrasive blasting (‘sand blasting’)

In

this method a dry abrasive is fed into a hopper

and a jet of high pressure air with a steady flow

of dry abrasive is directed through a nozzle

against the substrate. The use of dry abrasive

produces a great deal of dust and the spent

abrasive must be cleaned up and disposed of

afterwards.

The type and size of aggregate, flow rate

and pressure can all be varied, as can the

nozzle size, distance from and angle to the

substrate.

Dry ice blasting

In this method solid

CO

2

, which is formed into 3mm rice-like

pellets, is accelerated to supersonic speeds via

a blasting unit and applied using a hand-held

blasting gun through a fragmenting nozzle.

Upon impact the dry ice immediately turns

from its solid state into carbon dioxide vapour

expanding by up to 540 times its volume. The

energy produced by the conversion of solid

to vapour is considerable and is responsible

for much of the cleaning process. The vapour

disappears back into the atmosphere, leaving

only the removed contaminant for disposal.

Wet abrasive blasting

Including a small

proportion of water in the blast results in

less dust than the dry version, so it is easier

to see and control its effect. One system

commonly used by conservation contractors

creates a swirling vortex using a mixture of

low air pressure, a small quantity of water

and an inert fine granulate such as calcium

carbonate. The nozzle cone is interchangeable,

with a larger one for cleaning larger areas and

a smaller one for more intricate detail. The

pressure, type of abrasive and ratio of abrasive

to water can also be varied, as can the distance

from and angle to the substrate.

CHEMICAL METHODS

There are many chemical products on the

market with differing characteristics and

varying degrees of effectiveness depending on

the paint type and substrate being cleaned.

Many of the chemical removers are

applied to the surface in a poultice at 3–6mm

thick according to the thickness of the paint

layers. They are then wrapped in cling film

Typical heavy black gloss paintwork on internal ceiling joists

Timber surface before and after sandblasting