5 2

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 6

T W E N T Y T H I R D E D I T I O N

2

BUI LDING CONTRACTORS

are comparatively slow-acting and represent

long-term rather than immediate threats,

which makes them more difficult to anticipate

and identify. However, despite their chronic

rather than critical nature, their effects can

be severe and irreversible and the cost of

rectifying widespread damage of this type can

be extremely high.

Most of the risks are not uncommon and

could be anticipated at a very early stage of

the project. However, problems tend to occur

because the right questions are not asked

at the right time. At an early stage of any

project, the question that should be asked is

‘What are the possible negative impacts of

the proposed intervention and how can we

mitigate them?’ In most cases, as long as the

risks are identified sufficiently early, the design

can be adapted with only limited impact on

the overall outcomes of the project.

BUILDING PERFORMANCE

ASSESSMENT

The process by which the relevant issues are

examined can generally be referred to as a

building performance assessment. In simple

cases, this can be performed by HLF grant

applicants with their existing professional

advisers being armed with the correct set of

questions. In the proposed guidance notes

which the HLF is currently preparing, the

key risk areas are identified and relevant

questions are outlined. For the more complex

cases or those where the risk is of serious and

irreversible damage, it may be necessary to

have a more detailed assessment undertaken

by a specialist.

In most cases the building performance

assessment involves answering four basic

questions:

• How should the building

perform in its natural state?

• How is the building currently performing?

• What are the likely effects of

the proposed project on the

environment and performance?

• If the effects are potentially negative,

what mitigation measures can be put

in place which will allow the project

to proceed while minimising risk to

the historic fabric and artefacts?

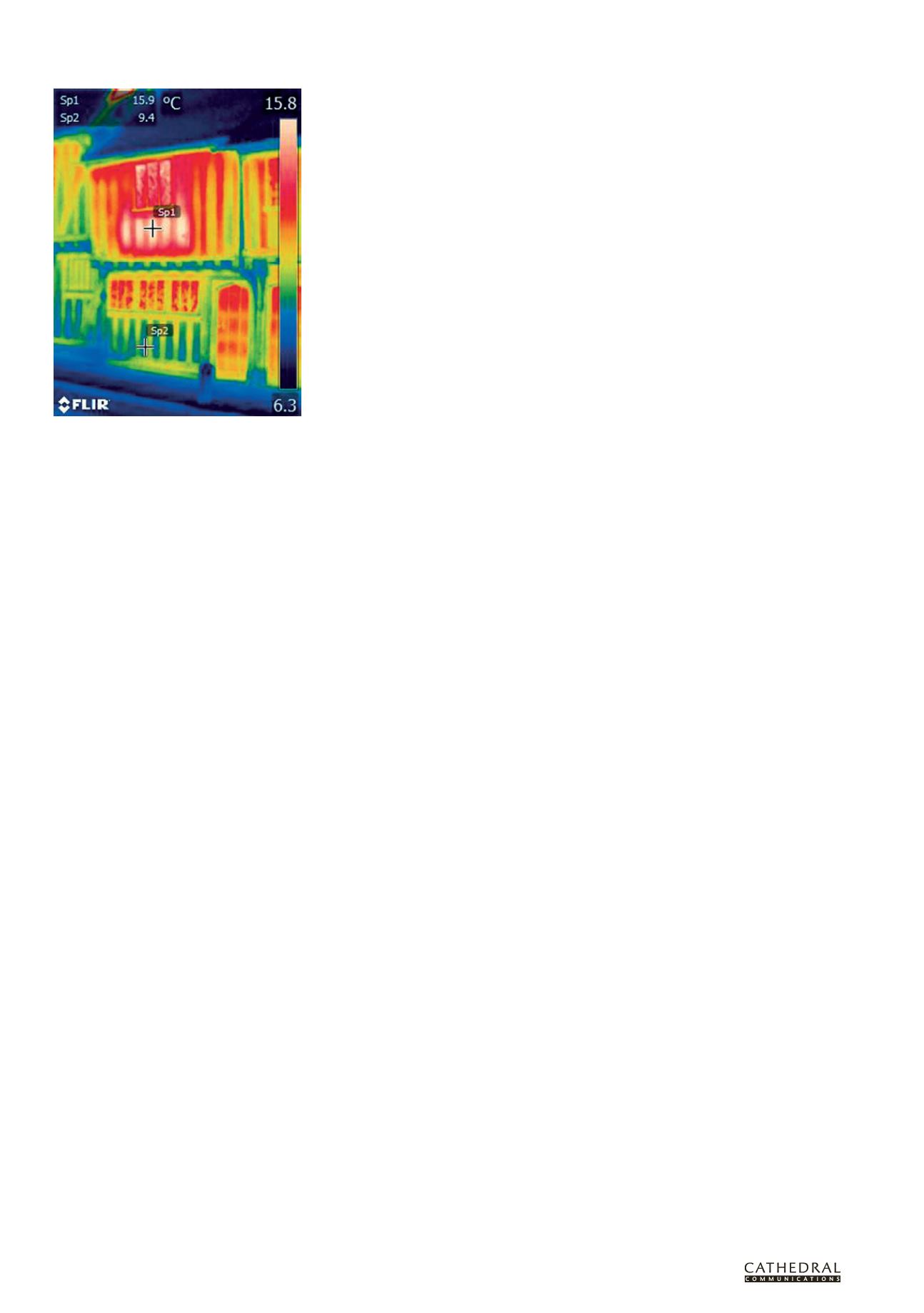

The nature and extent of a formal building

performance assessment can vary significantly

depending on the complexity of the project

and the relevant risks. A simple assessment,

which is likely to be appropriate in all but

the most complex projects, usually involves

a site examination and building survey and a

short report, and takes no longer than one or

two days. Thermal imaging and spot readings

for humidity, liquid moisture, light and UV

radiation are commonly used in investigations

of this type. In the more difficult cases

environmental monitoring, materials analysis

and other techniques may be necessary.

Investigations of this type take longer (most

environmental monitoring programmes

last a minimum of 12 months) and are more

costly and are therefore only appropriate

in a minority of cases. In all events, it is

very important to ensure that the type of

assessment carried out is appropriate for the

project and that the information which comes

out of the work is of practical use.

As well as being a risk assessment exercise,

a well-designed building performance

assessment may also be able to offer significant

benefits to the project. For example, advice

may be provided on how best to improve the

thermal performance of the building and to

therefore achieve greater comfort for the users

with reduced energy input (something which

often benefits the historic fabric as well). Advice

may also be provided on how using different

decorative coatings (for example limewash or

distemper instead of emulsion) might maintain

a more porous building structure, improving

moisture buffering and reducing the risk of

condensation. In fact, the results of a good

building performance assessment should be

to improve the environmental aspects of the

project rather than simply to prevent damage.

One area where this is particularly

relevant is heating. Project proposals often

state that there is an intention to increase

or improve the heating of the building. In

fact, it is rarely the case that people wish

to use expensive energy to heat a very large

airspace with only a small number of people

at floor level. Indeed this can often result in

significant risk to the building fabric. Rather,

it is usually the intention of the project

to provide thermal comfort for that small

number of people in the lowest two metres of

the building at the minimum cost (in financial

and carbon footprint terms), with minimal

harmful impact on the historic building or

any artefacts. To achieve this, it is important

to understand issues of energy loss and energy

input, as well as how the building is to be used,

by whom and for what periods of time.

Another area where problems

commonly occur is with the proposed use

of compartmentalisation and screens in

a historic building which was originally a

single large space or series of large spaces.

When used effectively, screens and internal

walls can be a useful tool in containing

the local microclimate and ensuring that

comfortable conditions are produced in

the most heavily used areas of the building

and where they have least impact on the

rest of the building. However, the same

containment can also focus harmful

conditions on sensitive fabric and artefacts,

increasing the risk of damage to them.

Combined with increases in visitor numbers

or the installation of catering facilities,

interventions which have the potential to

have a benign impact on the building can

swiftly become the focus of the problem.

A well-designed building performance

assessment can provide advice not only on

how to avoid harmful effects but also on how

to achieve the most effective environmental

controls for the benefit of both the users and

the historic fabric.

It is important not to confuse this type

of assessment of the building environment

with that undertaken to improve energy

performance. In many cases an energy

performance assessment has a primary aim

of increasing user comfort and minimising

carbon footprint with the building considered

as a neutral vessel within which the controls

take place. Often the measures which best

improve energy performance also increase

the risk to the building and artefacts.

A common example is the use of fan convector

heaters, which can swiftly change the air

temperature. This is often a benefit in terms

of comfort and energy use, but the same

sudden fluctuation in temperature and

humidity can have a particularly damaging

impact on historic structures and their

contents. Therefore, it is important that the

building environment and conservation

issues are addressed alongside any energy

performance environmental surveys.

This new emphasis on building

performance has been designed to draw the

attention of HLF grant applicants to the issues

associated with building environment and

the relevant risks. It is intended that it should

create little additional work in most cases and

should help to avoid time-consuming and

costly reworking of the design at a later stage,

which has sometimes occurred when these

issues have been overlooked. Ultimately, the

aim is to improve the long-term outcomes of

conservation and development projects for the

building user, while minimising the risk to the

building and artefacts.

TOBIT CURTEIS

runs Tobit Curteis Associates

LLP

(www.tcassociates.co.uk), a practice

specialising in the conservation of wall

paintings and the diagnosis and control

of environmental deterioration in historic

buildings. He is an external consultant for

the Building Conservation and Research

Team at Historic England and is the National

Trust’s advisor on wall paintings.

SARA CROFTS

is an architect and head of

historic environment at the Heritage Lottery

Fund

(www.hlf.org.uk). The HLF uses money

raised by National Lottery players to help

people across the UK explore, enjoy and

protect the heritage they care about.

Thermal imaging and spot readings for humidity,

liquid moisture, light and UV radiation are

essential features of a typical building performance

assessment. (Image: Tobit Curteis)