Alarms for Church RoofsAngus Brown

Although lead theft is not such a regular news item as it was in 2013, the threat to historic buildings from this crime has not gone away. Lead theft is directly linked to its scrap value which has soared during the last six years from less than £400 per tonne to a peak of more than £1,200. With a current price of £950 per tonne, churches are still being targeted for the lead and copper on their roofs. For example, between 2000 and 2004 there were just 20 thefts of metal a year from churches across the country, however between 2007 and 2011 these increased to more than 14,000 reported cases, at a cost of more than £32 million. Churches are perceived as fairly easy targets, particularly in isolated settings, and specialist insurer Ecclesiastical (EIG plc) reports that it is still receiving more than ten metal theft claims per week. The true cost of stripping lead from a church roof is, of course, not simply the cost of the replacement material: there is often a very wide discrepancy between the small quantity of metal stolen and the damage recklessly caused in the execution of the theft. Metal thieves who target historic churches cause damage which goes far beyond the value of the metal that is stolen. In some cases, the damage caused by rainwater ingress extends to medieval wall paintings and other irreplaceable pieces of art and historic fabric. There is clearly a graduating scale of metal thieves which ranges from the ‘chancer’, the opportunistic and small-scale offender who is after quick cash, to the highly organised and specialist criminal who will strip entire roofs. In general, however, research has shown that the sophistication of thieves targeting metal roofs tends towards the lower end of the scale. There has also been concern regarding scrap metal dealers, with their ‘no-questions-asked’ approach and an industry-wide refusal to ban cash-based transactions. Only when the government introduced a new law in England and Wales regarding these issues were dealers south of the border forced to adapt. DETERRENCE

Since lead thieves who are interrupted can still cause expensive damage, the use of 24-hour monitored alarms with audio or CCTV verification is increasingly considered to be ineffective in protecting the historic fabric of an ancient church. The potential thieves need to be deterred before they do any damage. Deterrence starts at the perimeter, with notices advising would-be burglars of the measures that have been taken to prevent theft. These may include the use of physical deterrence systems such as alarms, anti-climb paint, ‘DNA’ marking systems which enable stolen material to be identified, and lead sheet locking systems that make it difficult to strip a roof of its lead quickly and quietly. Deterrence may also include community involvement through neighbourhood watch schemes or notices inviting members of the public to call the police if they see suspicious vans or workmen between 6pm and 8am. Visibility is another key component of this first layer of defence. Is the building overlooked by houses, does any vegetation need to be cleared to provide a better view? Most criminals can be deterred by knowledge that the site is regularly overlooked and checked. The second layer in the deterrence approach is an alarm system. Its aim is to ensure that intruders are detected and deterred the instant they go where they should not be and crucially, before they have done any damage. ACCESSIBILITYWhen looking at the security of a historic church it is essential to remember that the building is regularly open to the public and although it may contain important historic fabric and have a lead roof, the public needs to be able to access the site without impediment. There are many ways of impeding access by would-be thieves and these can be as simple as making sure that ladders and tools are secured and not accessible. Looking at the perimeter of the site, can it be ensured that only authorised vehicles have access? Looking at the building itself, are there parts of the building design which might enable easy access to the roof? A boiler house might provide the perfect spot to climb up onto the aisle. In these cases are there any other physical measures that can be installed to help deter access to the roof, such as anti-climb paint or security lighting. The key issue for historic churches is to ensure that any physical intervention does not compromise the appearance of the building, so 18ft-high razor-wire fences are not always possible.

STRATEGYA truly comprehensive security management plan blends physical, electronic and procedural aspects of protection, while respecting the context in which it is being installed. So not only do you look at the simple actions mentioned above but also the protection that technology can provide and how those people who are responsible for the building behave. This is fundamental to the process of developing a comprehensive security strategy and without internal policies and procedures – as well as a proactive security consciousness – physical and electronic security hardware and features will fall short of their intended goal. A security strategy is developed by evaluating the assets, considering the threats against them and developing countermeasures to reduce their vulnerabilities. This is achieved by layering security, both physical and electronic, thereby creating defence in depth. This approach to security is designed to deter a crime in the first instance, to delay access to and the removal of target assets and to detect an attack at an early stage, should one occur. Thus potential criminals, having inspected the property, may be deterred from undertaking a burglary by the sight of robust physical security, intrusion sensing and external lighting. Should they decide to proceed, physical measures will delay access to target assets and the alarm system will provide an early indication of attack and may summon an effective response. THE ALARM SYSTEMIn 2010 alarm specialists E-Bound AVX Ltd worked with Ecclesiastical Insurance Group (EIG plc) to refine a simple but effective strategy for the protection of historic church buildings as part of EIG’s ‘Hands off our church roofs’ campaign. The three key requirements identified were:

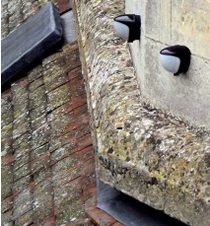

A typical system consists of a control panel, wireless passive infrared movement detectors, audio alarm sounders and strobe lighting. The detectors are battery operated and communicate with the control panel via radio signal using a frequency designed to suit the thick walls, lead roofs and other features typically found in church architecture. As a result, the only cabling required is from the control panel to the mains power supply and to the sounders, and a typical installation can usually be deployed in one day, subject to survey. The control panel may be installed in the church or an ancillary building and should be connected by mobile phone technology to a 24-hour monitoring and response centre. On the roof of the church, the audio alarm typically involves a short burst of a siren followed by a pre-recorded challenge warning the intruder to leave immediately and making clear that people are responding to the alarm. The message ends with another short burst of the siren. A sequence like this which includes a good, clear spoken challenge has been shown to be far more effective at deterring intruders than a siren alone. Despite many similarities, each historic place of worship is unique, and each alarm system must be designed on a bespoke basis. There is no off-the-shelf solution: for the alarm system to work effectively, each site needs to be considered on its own merits, and each detector needs to be tailored to suit the parameters of its location. Not only are there variations in design and construction to be taken into consideration, but there are also variations in the requirements of the people, usually volunteers, who look after the building. Both sets of requirements must always be considered carefully for an alarm system to be effective. Where historic fabric is concerned, it is also important that the alarm system has been developed in consultation with historic building professionals, to ensure that the system is as compatible as possible with historic fabric. Equipment should be as small and unobtrusive as possible and great care must be taken over the fixings. The positioning of detectors and panels must be thought through for ease of installation and operation, as well as for aesthetics. The alarm system must be based on the proven catch capabilities of industry-standard detectors but without the inherent risk of regular false alarms usually associated with outdoor installations. The best roof alarm systems have been developed as roof alarms from the outset. Adaptations of existing systems, designed for homes, factories, shops and the like will not be able to cope with the unique challenges posed by buildings with extremely thick walls and a variety of no-go areas which must be monitored in isolation from other areas. Detectors often need to be tailored to suit odd angles, or to eliminate background radiation or movement, requiring a range of lenses and sensors. Monitoring is essential so that there is a response when the alarms are set off. In addition, systems should include tamper protection on all detectors and the control panel, along with mains power monitoring. The company monitoring the alarm should also be alerted in the event that mains power is lost and not restored. The alarm should have rechargeable back-up batteries which will run the system for several days in the event that mains power is lost. Once power is restored, these batteries automatically re-charge. When integrated into a broad strategy for the protection of churches, dedicated roof alarm systems provide a simple but highly effective form of deterrence. At Puddletown in Dorset, for example, St Mary’s Church had a spate of attacks in mid-summer 2010, striking at the lead valley between the nave and aisles. What was particularly galling was the fact that the thieves cut out the base of the gutter near the outlet, so water from the whole expanse of roof came through the hole into the church below, causing extensive damage. It was also very difficult to make a temporary repair watertight in this area. An alarm was installed in September 2010. Within two weeks of the work being completed the PCC was advised that the alarm had been set off at 2.30am on a Saturday. On attending the church that morning, finger marks were found in the anti-climb paint on a drain pipe and there was evidence that an attempt at a further theft had been made, this time without causing any further damage. Now, four years on, the installation is still working well and has attracted the attention of Dorset Police crime reduction officers and other churches in the region. ~~~ Further InformationChurchCare (the Church Buildings Council’s website) publishes various guidance notes including one on alternatives to lead Ecclesiastical (EIG plc) provides information on lead theft protection English Heritage co-ordinates the Alliance to Reduce Crime against Heritage (ARCH), a voluntary national network which includes churches, police authorities, local authorities and other organisations Historic Scotland publishes a short guide on lead theft and traditional buildings

|

Historic Churches, 2014 AuthorANGUS BROWN, founder and managing director of E-Bound AVX Limited, has held a number of security-related roles since leaving the British Army over 20 years ago. He has brought the disciplines and skills he learned while working for British intelligence to bear in developing modern security products and services. Email angus@e-bound.co.uk Further informationRELATED ARTICLES

RELATED PRODUCTS AND SERVICES

© Cathedral Communications Limited 2015 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||