Aesthetic Protective Glazing

Mark Bambrough

|

| The whole window showing both the aesthetic protection (central light, upper middle section) and the mirror image protective glazing above and below it |

For conservators, stained glass windows present some of the greatest challenges in the field of conservation. On the one hand they include some of the most spectacular works of art in this country; on the other they are integral elements of architecture. In church windows, they are continually buffeted by wind, soaked by the rain and scoured by air-borne particles. Even condensation on the inner face takes its toll, supporting organisms which, over the centuries, erode the decorated surfaces. In order to preserve historic glass in its original location it has now become common practice to protect the most fragile and special examples by moving them from their original position to the inner face of the opening, with a new protective glazing system behind, separated by a slight air gap. Warmer air on the inside of the building is thus allowed to circulate around both sides of the original glass, protecting it from condensation (the 'isothermal' system).

Internally, the change in the position in the glass has surprisingly little impact on the appearance of the stained glass as it is still seen in its original framed opening, albeit with a very different structural support mechanism. However, externally the new protective glazing presents a very different story, even when the glass pane is broken up into small panes of leaded lights which mirror the original glazing pattern. Firstly, the doubling of the lead matrix creates the so-called 'tramline' effect, both inside due to the shadow cast by the lead of the protective glazing, and outside due to the appearance of the original lead through the clear glazing. Secondly, the appearance of the original glass through clear protective glazing, although 'honest', is in itself distracting, as is the reflection off the protective glass. The latter may be reduced by using low -reflective glass, but as yet the best available still shows reflection in raking light. And, thirdly, the use of lead cames with clear glass creates an architectural aesthetic that is very different from that of stained glass and without any historical precedence. In this respect, the use of clear glass sets the protective glazing system apart from the building by denying the importance of what was there before, and by ignoring the stained glass windows' aesthetic and historic contribution to the building, it also denies the whole sense of mystery that stained glass windows have when seen from the outside.

Given these design limitations, all of the compromise currently has to be accommodated by the building and not the stained glass. If we consider the window to be an integrated and unified part of architecture, where the two elements are intended to work together, by changing their relationship to each other we radically alter the centuries-old dynamic between glass and stone, image and structure, transparent and solid.

|

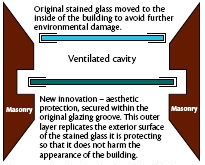

| Above: Diagrammatic section showing the relationship between the original stained glass and the protective glazing |  |

| Seen from inside, the upper middle section of the central light is just as bright as the others, despite the new aesthetic protective glazing. Below right: this detail highlights the difference in the reflective qualitites of both the aesthetic protection (central section) and the mirror image, which is not present in the aesthetic protection because its surface appears opaque. |

PARAMETERS

The aim of

the experiment was to create a system of protection that would

preserve the aesthetic integrity of a building's exterior, by

developing a system that minimised any visual impact upon its

host structure. The premise that underpinned this experiment was

the primary significance of architecture over and above the decorative

arts that adorn it. As Owen Jones stated, 'The decorative arts

arise from, and should properly be attendant upon architecture'

(Grammar of Ornament, 1856). Stained glass evolved as an integral

element of architecture, and it should continue to be seen as

such. Architecture is not there to showcase stained glass.

This experimentation therefore questioned the motives of protective glazing in putting transparency before replication. In particular, if honesty equates to transparency, does making the protective glazing imitate the stained glass necessarily amount to deception? What truth is there in a 'mirror image' lead-line caricature of the original without its life, colour and spirit? And is this more honest than trying to faithfully replicate and retain the essential relationship between glass and stone? It could be argued that a deception in this case has a greater truth for the building and therefore has more historical and aesthetic legitimacy than any other form of protective glazing.

This presented significant challenges. In addition to replicating the character of the exterior face of the original stained glass, the solution also had to have minimal impact on the appreciation of the original stained glass from the interior. The isothermal system with mirror image leading provided the benchmark, and the key issues for comparison therefore included:

- the amount of transmitted light it blocked out

- the recreation of an exterior appearance

- the reduction or elimination of glare and reflection

To have any credibility, the experiment had to be part of a real project, and it had to enable the new system to be compared with the current industry standard, the 'mirror image'. A test bed was therefore set up at Newkilpatrick Church in Glasgow in which it would be possible to view both methods side by side. The window was already suffering from extensive paint-loss and permission to install isothermal glazing had already been granted.

THE TECHNIQUE

All exterior stained glass surfaces have varying degrees of colour and shade within them. Each pane also breaks up and reflects the light away from the surface at different angles. To capture these exterior characteristics within a protective layer, the process chosen involved replicating the exterior appearance of a stained glass panel by transferring a photograph of the panel on to clear glass through screen printing, and then slumping it into a mould to create the lead line pattern. Because the coloured layer is extremely thin, this glass is almost transparent to transmitted light, and there is no more light lost than from the mirror-image leading of conventional protective glazing. When mounted with the original stained glass behind, the experiment confirmed that it was also opaque to reflected light. The surface therefore reflects both the two-dimensional structure of the lead pattern and the colour of the painted surface, in much the same way as the original. The gap between the two planes, ideally of 25-50mm, effectively forms a light-well across which any image or shadow cast by the decoration on the protective glazing is almost completely diffused on the inner (original) glass.

|

The experiment confirmed the following advantages:

- The system accurately reproduces the form and detail of the original window externally; no other system does this.

- It is impossible to see through its surface to the stained glass beyond, so there is no confusion between the protective glazing and the stained glass. Your eye is forced to look across the same visual plain as it would have done with the original stained glass. It also eliminates any parallax problems, because the lead lines are translucent, not opaque.

- The system is visually warmer and casts softer shadows than one with mirror image leading.

- As each panel comes in one piece, it can either be laminated or toughened. The lamination could also be a UV inhibitor to stop the most damaging effects of light. The degradation of epoxy resin repairs in UV light has long been an issue; this system could prevent that degradation.

- Finally it responds to surface light-play in the same way as stained glass, and does not give off glare or reflection. It thereby retains the relationship between glass and stone.

Irrespective of what method of protective glazing is used, both internal and externally ventilated systems will always entail some loss of authenticity. This, however, does not mean that protective glazing must look incongruous or ruinous to a building. Our challenge as conservators is to develop new ways of dealing with the problem which strive to maintain the historic relationship between glass and stone. Furthermore, these new techniques should allow stained glass to be protected without that protection being achieved at the expense of the building as a whole, which may be of far greater significance than the glass itself.