Solitude and Sociability

The World of the Medieval Anchorite[1]

Mari Hughes-Edwards

|

|

The ‘Meeting of Saint Anthony and Saint Paul’, bythe Osservanza Master, c1430: Saint Anthony, whospent

much of his life as a desert ascetic, and SaintPaul, the hermit, were role models for recluses and other medieval

contemplatives. (Image: National Gallery of Art, Washington) |

Religious men and women have been inspired to seek lives of solitude since ancient times, moved by the belief that spiritual fulfilment can be found in the rejection of society’s expectations and encumbrances. The desert fathers and mothers, the earliestknown Christian solitaries, were inspirational role models for the professional contemplatives of the Middle Ages. They withdrew from the world for the same fundamental reason as their medieval counterparts did: that they might better come to know themselves and, through that self-knowledge, generate a more intimate connection with God.

In England, during the Middle Ages, the desire to experience religious solitude was commonly mediated through physical enclosure and could manifest as coenobitic withdrawal, which is community-based, as eremitic seclusion, or (certainly in the earlier Middle Ages, at least) as an individualised combination of the two. Medieval eremites, that is, hermits and anchorites, experienced the harshest forms of solitude known to medieval society.

The term anchorite comes from the Greek άναχωρητής (anachoretes), itself derived from the verb άναχωρειν (anachorein, ‘to withdraw’).[2] Anchorites then, were men and women who sought to withdraw from the world as much as was practicable, often (although not always) to a small, four-walled cell adjoining a religious building. Sometimes referred to as the medieval world’s living dead, many spiritual thinkers have written for them and about them, inspired in part by the deeply dramatic notion of grave-like spatial fixity upon which the vocation is founded.

In contrast to the eremitic seclusion of hermits who could, in theory at least, move locations, anchorites were permanently enclosed within the walls of their cell or ‘anchorhold’. They remained in the world and yet were manifestly not of it. They retreated to a spatially restricted spiritual arena, the better to confront the very worst that was in them. They engaged in this spiritual struggle not only for themselves, but for the wider world which, paradoxically, the vocation was developed to reject.

CONSTRUCTING THE PAST

Drawing on evidence available to her in the mid-1980s, based partly on the invaluable tabulated lists of cells in Rotha Mary Clay’s The Hermits and Anchorites of England (1914), Ann K Warren in her Anchorites and their Patrons in Medieval England (1985) identified at least 780 recorded English recluses on 601 sites.[3] Warren also proposed that more English women than men were enclosed at every stage of the period, detailing 414 female solitaries, 201 males and 165 of unknown gender. Warren located anchorholds in all but four counties of medieval England (Buckinghamshire, Rutland, Cumberland and Westmorland), noting that some counties demonstrated evidence of strong anchoritic identities, including Oxfordshire, Sussex, Worcestershire and Hampshire, during the 12th and 13th centuries, and Lincolnshire, Middlesex (including London) and Norfolk, throughout the Middle Ages. Some counties may have demonstrated marked anchoritic links only at certain times, as with Yorkshire, where anchoritism appears to have declined by the end of the 15th century.

|

||

| The chancel of St Nicholas Church, Compton, Surrey: the upper part of this unique two-tier chancel is reached from a stair inside the anchorhold on the right (south side). The window of the anchorhold on the north side can be seen bottom left. |

The vocation began as a largely rural phenomenon, and for most of the medieval period rural anchorholds predominated. However, the number of English urban anchorholds steadily increased until the 16th century by which time, as Roberta Gilchrist argues, the anchorhold had become ‘an integral element of the ecclesiastical topography of medieval towns’.[4]

Yet detailed information about the gendered identity, geographical distribution and chronological development of English anchoritism is still emerging. Warren’s and Clay’s statistical picture is already changing as new sites and solitaries are discovered. Edward A Jones, at the University of Exeter, is currently revising Clay’s 1914 lists of solitaries, and his investigations have resulted in the publication of updated lists for medieval Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire and Huntingdonshire which, when combined, feature 50 solitaries compared with Clay’s 24.[5] How the new data will contribute to our understanding of anchoritism is, as yet, unknown, but it need not imply radical change in anchoritism’s gendered, geographical or chronological make-up. Warren’s original depiction of the vocation as ‘a wide-ranging and far-reaching religious phenomenon: many anchorites all over the country… Not one in every parish, but in many’, may yet remain true, even if the vocation appears to have been more widespread than either Clay or Warren could have imagined.[6]

Our knowledge about anchorites is based on two broad kinds of evidence: archaeological and documentary. Neither kind of evidence affords us the objective ‘truth’ about how anchorites actually lived, but instead offers us a series of ideological pictures, or subjective ‘truths’ about the vocation. Some of these pictures do indeed construct the medieval anchorhold as a solitary death cell, in which the recluse endures simply as a living corpse, locked up in death-like darkness. Yet others reveal the less critically prominent, but equally valid, depiction of a busy woman who willingly interrupts her devotions to be of spiritual service to a steady stream of visitors. As the vocation was never standardised and never constituted a religious order in itself (although members of religious orders could, and did, become recluses), it would therefore be unwise to make wide-sweeping generalisations about anchoritism on the basis of individual cells, documents, or lives. Nevertheless, it is clear that much of the surviving evidence presents anchoritism as highly esteemed by the surrounding community, a community which, after all, enabled the vocation to exist and persist in both economic and practical terms.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

|

|

| An illustration of the anchorhold at Hartlip, Kent from Rotha Mary Clay’s The Hermits and Anchorites of England, published in 1914 (Photo: PM Johnston) |

Archaeological evidence of the vocation is scarcer for the earlier medieval period, and tends to reveal the prevalence of small, one-roomed cells, not multi-roomed establishments.[7] Recent work by Tom Licence describes the makeshift nature of the earlier medieval anchorhold: ‘the vast majority were lean-to, timber structures rather than the solid domiciles of stones which first came into view in the 14th century’.[8] Many cells were attached to or close to churches, although some were part of convents, monasteries and even castles and Gilchrist concludes that the majority were built on the inhospitable northern side of the chancel, although the placement of some female-inhabited cells may have been to the west.[9]

The smallest known cells are those of Leatherhead and Compton in Surrey. Leatherhead’s cell was 2.4 metres square, with a window of 53cm square, while Compton’s was 2.0 x 1.3 metres, with a loft where the recluse may have slept.[10] Warren’s plan of Compton in the 12th century illustrates its tiny dimensions, yet this cell was occupied by anchorites from 1185 to the early 14th century.[11] Gilchrist describes both sites, noting the existence of two cells at Compton, one to the south of the chancel and an upper chapel at its east end which may have served as ‘the oratory for an anchorite-priest’.[12] Later medieval anchoritic architectural remains imply that some cells continued to be small one- or two-roomed structures, although notable exceptions may include the four-roomed anchorhouse at Chester-le-Street and the 8.85 by 3.65 metre cell of one 15th-century anchorite priest.[13]

Some later cells seem to have had gardens, although this too appears to be exceptional. Of the 15th-century anchorhold at the Charterhouse of Sheen, Warren affirms: ‘The anchorite paid an annual rent of eight pence for a garden “newly walled”’, while Emma Scherman of Pontefract was apparently given permission to be rehoused because her garden was too noisy.[14]

WRITTEN EVIDENCE

Surviving written evidence for the English anchoritic vocation, more extensive for the later medieval period, includes ceremonies of enclosure, wills, court documents, bishop’s registers, ecclesiastical documents, personal correspondence and anchoritic guides.

The earliest ceremony of enclosure, detailing the final liturgical moments of an anchorite’s life in the world, is recorded in a 12th-century pontifical (a liturgical book of rites) and the latest in a printed 16th-century manual. In theory, such ceremonies were undertaken after permission for enclosure was granted, satisfactory financial arrangements located and an anchorhold built or chosen. Not every recluse would have participated in one; enclosure required only investigation into the candidate’s spiritual reliability, financial security, intended domicile and the granting of an enclosure licence. Nonetheless, the enclosure ceremonies that survive are rich in the rhetoric of death, using it to signal an end to the postulant’s earthly life, to demonstrate permanent separation from the world and to celebrate the recluse’s new fixity of abode.

|

|

||

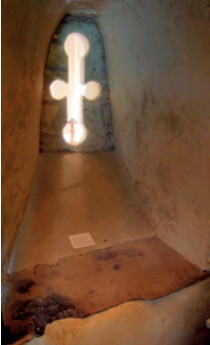

| The anchorite’s window on the south side of St Nicholas, Compton seen from the altar (left), and the view of the altar from the interior (right). The wooden cill on the inside is believed to be original, worn down by centuries of use. | |||

The wills in which anchorites feature usually document small individual bequests and, sometimes, gifts made to the recluses of one geographical area. Infrequently, they detail lifetime endowments for individual recluses. The percentage of wills that mention anchorites is relatively small. Warren notes that only ten per cent of the wills calendared at the London Court of Husting between 1351 and 1360 make reference to them.[15] Nonetheless, they demonstrate the visible support which the (often lay) community gave to the vocation and the esteem in which it was held.

Other indicators of esteem include documented visits of those of high status to various reclusoria for advice. Westminster recluses were consulted by Richard II and Henry V, while a female anchorite from Winchester was brought to see Richard Beauchamp, the Earl of Warwick, in London because he was too busy to travel to her.[16] Emma Rawghton, of All Saint’s Church, North Street, York, renowned for her visions of Mary, was also linked to Beauchamp and made predictions about his future.[17] Jones acknowledges renowned later medieval recluses like Julian of Norwich (c1342-c1416), Rawghton and the Winchester anchorite as rare but not unique examples of ‘a female anchorite occupying a position of spiritual authority’.[18] Nonetheless, these medieval recluses were evidently considered and consulted as agents of the Lord and these visits suggest the potential respect with which medieval society treated at least some of its solitaries.

General ecclesiastical documentation, including episcopal registers and court documents, focuses on the vocation’s clerical support and its operational issues. For example, the episcopal registers of John Stratford, Bishop of Winchester, record the case of Christine, anchorite of St James’s Church in Shere in Surrey, who sought enclosure in 1329 but had fled her cell by 1332.[19] Others record alleged sexual scandal, such as that at Whalley in Lancashire, where an account of the supposed sexual misconduct of the servants of the anchorite Isolda de Heton (enclosed in 1436) suggests that another anchorite absconded: ‘dyvers that had been anchores and recluses in the seyd plase aforetyme, contrary to thyre own oth … have broken owte of the seyd plase’.[20] Like Christine, Isolda seems to have left her reclusorium. A widow with a young child, she may have gone into hiding with her son. The Cistercians of Whalley Abbey petitioned Henry VI to allow them to convert the anchorhold to other uses.

|

|

|

| The anchorhold on the south side of Compton’s chancel (above left) still survives as it contains the staircase to the chancel loft, but the one on the north side (above right) has gone, leaving a recess surrounding a small square window. | ||

Usually, however, the operational documents that surround the vocation are less controversial. They detail pre-enclosure background investigations and post-enclosure provisions for support, for example in terms of licences and mandates which detail the building of anchorholds, the replacement of unsuitable cells and the legislation of diet. On rare occasions they record the rights given to recluses to leave their cells temporarily, as in the case of Emma Scherman, who may have been permitted to make an annual pilgrimage.[21]

Some of the documentation which surrounds anchoritism constructs the vocation as acceptably sociable. Henry Mayr-Harting concludes of the socially-active recluse Wulfric of Haselbury: ‘Anyone living in twelfth-century England would very probably… have had contact with a recluse’.[22] This is echoed by Licence’s assertion that: ‘Set at the heart of the community… it was an unwise recluse that entered her cell to achieve peace and quiet’. Licence argues that recluses potentially ‘provide a ministry different from the priest’s’, involving three key elements: inspiring repentance, interceding on behalf of the faithful and, lastly, mediating God’s power.[23] Some of the sources that surround anchoritism imply then that anchorites were not cut off from society, but rather attempted, as much as was possible, to withdraw from it. Ironically, they could not do this without the compliance of the very society that they strove to reject.

|

|

| The chancel of St John the Baptist, Ruyton XI Towns, Shropshire, displays typical archaeological evidence of an anchorage which stood against the north wall of the chancel, just behind the war memorial. |

English anchoritic guidance texts were also written, revised and translated, chiefly from Latin into English and vice versa, throughout the Middle Ages (c1080-1450) to enable recluses to come to terms with the enormity of their choice. The guides imply that the anchoritic life is one of privation and paradoxical joy because of the God-given grace required to make it bearable. Frequently written in the form of a letter from one writer to one recluse, they range in size from short epistles to intricately subdivided works. Warren argues that 13 English guides are extant but it is difficult to be precise about numbers.[24]

It is tempting to read anchoritic guides as evidence of widespread reclusive practice, especially given the dramatic, visual nature of earlier medieval guidance, coupled with the relative lack of documentary evidence for that early period. Yet what the guides show us is not how recluses actually lived, but what a handful of talented medieval thinkers hoped a number of recluses could achieve at their best, or fail to achieve at their worst. They are rich in the rhetorical theory of anchoritism: complex normative works of instruction, shaped by the ideological agendas of their age. They suggest that the vocation should be founded upon four key ideals: enclosure, comparative solitude, chastity and orthodoxy. The maintenance of each ideal is difficult and continually threatened by every recluse’s natural tendency to sin; a problem that the cell cannot solve, but is meant to intensify.

English anchoritic guides present the central goal of anchoritism as essentially the same for men as it should be, or could be, for women. That aspiration is not, according to the guides at least, extreme suffering (although some are deeply preoccupied with the punitive). The anchoritic life may involve suffering, certainly, but that suffering is not its goal. It is a means to an end, even for the earlier, more bloodthirsty guides. It is not for the power to suffer that the guidance writers argue that the recluse deserves to be admired, but for what that suffering signifies, for there is a contemplative covenant sealed therein.

For the guides construct the purpose of anchoritism as an increased ability to connect with God through heightened contemplative experience, which may or may not involve pain. This much sought-after contemplative experience does not necessarily preclude acceptable social contact between the recluse and the community which surrounds the anchorhold. The guidance writers imply that a range of anchoritic social functions are acceptable, for the vocation is founded upon comparative, not total, isolation. Anchoritism therefore involves, as the guides construct it, the desire for solitude, not necessarily the perfect achievement of it.

|

||

| The enclosure of an anchorite by a bishop: this early 15th-century illumination appears in the English version of a Pontifical manuscript (CCC MS 79) which details church services particular to bishops. The section (f 96r-98r) is entitled Ordo ad recludendum reclusum. (Image: Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge) |

Yet all guidance writers agree that the female recluse has a bigger problem than her male counterparts because she must overcome the legacies of Eve, in order to negotiate her contemplative potential. Women make both the best and the worst of recluses: they have further to fall (potentially at least), but, if they can overcome their inherent weaknesses, they may also rise higher. Certainly the dominant number of women who were attracted to anchoritism implies that this potential ascent was of significant interest to them. The guides argue that the anchorite’s cell potentially provides the female recluse with the opportunity, not to escape her Edenic tendencies, but rather to think through them and move beyond them.

For anchoritic guidance texts for women would not have been written at all if their writers did not believe in the very real power and potential of religious women. Their existence suggests that the female recluse was far more than a convenient target for medieval society’s inevitable anti-feminism. Indeed, many of the English anchoritic guidance writers acknowledge that they write for those who are capable of surpassing them, not only in transgressive potential (in truth the guidance writers are comparatively uninterested in this), but in contemplative capability. They are most intrigued by the transformative spiritual potential of anchorites, by their possible ascetical and contemplative agency.

From the perspective of a guidance writer, the spiritual agency to which their female recluses can aspire is two-fold: ascetical and contemplative. The later-medieval guides especially argue that the female recluse is, as a professional contemplative, potentially well placed to advise the laity on their own spiritual practices and, more than this, to help ensure their spiritual orthodoxy. These texts show us a recluse who can potentially disseminate anchoritic ideology and contemplative theology into the surrounding community. They imply that the medieval anchorhold is just as likely to house a recluse who suspends her contemplation to impart spiritual and material guidance to those that seek her wisdom, as it is to hide, in grave-like seclusion, one who functions as the living dead. The anchorhold portrayed in anchoritic guidance writing is thereby concurrently revealed, in ideological terms, as a potential site of intellectual exchange, spiritual progression and growth, and we see that despite its idealised, relative isolation, it is far from cut off from the outside world.

Recommended Reading

RM Clay, The Hermits and Anchorites of England, Methuen, London, 1914

R Gilchrist, Contemplation and Action: The Other Monasticism, Leicester University Press, London, 1995

R Hasenfratz (ed), Ancrene Wisse, Medieval Institute Publications, Kalamazoo, Michigan, 2000

M Hughes-Edwards, Reading Medieval Anchoritism, University of Wales Press, Cardiff, 2012

EA Jones, ‘Christina of Markyate and the Hermits and Anchorites of England’, in Samuel Fanous and Henrietta Leyser (eds), Christina of Markyate: A Twelfth-century Holy Woman, Routledge, London, 2005

T Licence, ‘Evidence of recluses in eleventh-century England’, in M Godden and S Keynes (eds), Anglo-Saxon England, 36, 2007

T Licence, Hermits and Recluses in English Society: 950-1200, OUP, Oxford, 2011

AK Warren, Anchorites and their Patrons in Medieval England, University of California Press, London, 1985

Notes

1 An extended discussion of some of the material cited in this article can be found in Mari Hughes-Edwards, Reading Medieval Anchoritism (see Recommended Reading).

2 HG Liddell and R Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1843, vol 1, p257

3 See Warren p19 and Clay’s tabulated lists of cells p203-63. Jones problematises Clay’s classification of solitaries by site and county, proposing instead classification by individual (pp232, 235).

4 Gilchrist, p183

5 For Jones’ findings to date, see his website Hermits and Anchorites of England; his ‘Christina of Markyate’, p240-50; his ‘The hermits and anchorites of Oxfordshire’, Oxoniensia, 63 (1998), 51-77 and his ‘Rotha Clay’s Hermits and Anchorites of England’, Monastic Research Bulletin, 3 (1997), 46-8.

6 Warren, p18

7 See T Licence, ‘Evidence of recluses in eleventh-century England’, 2007

8 T Licence, 2011, p87

9 Gilchrist, pp189-90

10 Warren, p32

11 See Warren, p29. HT Turner, ‘Notes on Compton Church, Surrey’, The Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, 12 March 1908, 4-7 (5), suggests the Norman origin of the two-storied cell on the south side and argues that its doorway is a 14th-century insertion.

12 Gilchrist, p187

13 See Clay, pp83, 214 (Clay records Chesterle-Street’s named recluses from 1383 onwards). Warren notes that references to an anchorite’s ‘houses’ are found in later medieval documentation but multi-roomed structures were exceptional, p32. See also Hasenfratz, Ancrene Wisse, p9.

14 Warren, pp50, 78 and Clay, p144

15 Warren, p190

16 Warren, pp163, 204

17 William, Earl of Carysfort (ed), The Pageants of Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, Roxburghe Club, Oxford, 1908; J Rous, Rows Rol, Pickering, London, 1845

18 EA Jones, ‘Anchoritic aspects of Julian of Norwich’, in L Herbert McAvoy (ed), A Companion to Julian of Norwich, DS Brewer, Cambridge, 2008, pp80-1, 82

19 We know that Christine fled her cell, but do not know for certain that she was re-enclosed, although the last letter that documents her case (dated November 1332) gives this or excommunication as her only options. See the episcopal register of John Stratford, Hampshire, Record Office, MS 21M65/A1/5, f46v and f76r.

20 Warren, pp182-3

21 Warren, pp77-8

22 See H Mayr-Harting, ‘Functions of a twelfth-century recluse’, History: The Journal of the Historical Association, 60 (1975), p337, which reveals Wulfric as potential conciliator, healer and scribe.

23 Licence, 2011, pp171, 163

24 Warren, appendix 2, pp294-8