Box and Yew Topiary

John Glenn

|

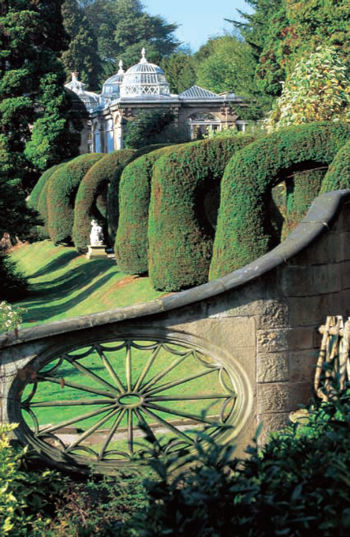

| 19th century Irish yew topiary at Alton Towers |

Nothing over the last three centuries has polarised gardening attitudes more than the art of topiary, and although the horticultural status of clipped Buxus sempervirens [L], box, and Taxus baccata [L], common yew, has varied with taste and fashion, their suitability as subjects for topiary and formal hedges has never been questioned. It has been argued that when clipped as green architecture no other plants give more harmony and distinctive character to formal and geometric gardens. Even the most vigorous exponents of the 'natural style', whilst ridiculing the bizarre excesses of topiary forms, have happily recommended yew and box as the best materials for clipped garden hedges.

Common yew and, to a lesser degree, box are long-lived and they are often the principal living survivals from earlier phases of historic gardens. Often associated with Tudor and Jacobean architecture, the history and nature of this living archaeological evidence has become surrounded by myth. Some features are reputed to be many hundreds of years old and, in one case, almost a thousand. But how old can they be? And how can living garden features have retained any semblance of their original shape all this time? Separating the facts from the mythology is important, particularly when considering conservation and restoration strategies.

|

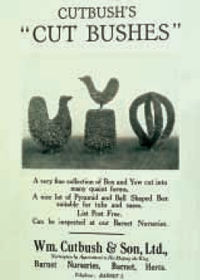

| By the end of the century when Cutbush's 'cut bushes' were being imported from the Netherlands, the popularity for topiary had outstripped native supply. |

EXPOSING THE MYTH

Unlike historic buildings, which require direct intervention to effect change, topiary and formal hedges will gradually alter shape over a few years, and substantial design drift can occur over a number of years. Even if the original philosophy of maintenance clipping has been followed, subtle changes in size or shape can and often do take place. Chris Crowder, the head gardener responsible for the world famous topiary at Levens Hall, states that every year he has been there the freehand clipping techniques they employ have subtly altered the shapes of the topiary. Formal yew and box hedges, properly managed and regularly maintained by skilled operatives, should in theory be less likely to suffer design drift. It is likely, however, that most historic gardens have experienced periods of economic restrictions and labour shortages, during which many hedges and topiary specimens were neglected. A staff of 90 gardeners once maintained the pleasure grounds of Elvaston Castle. Financial cutbacks reduced the labour force in 1852 by 90 per cent. As a result, the shapes of miles of formal hedges and the extensive number of large topiary specimens have changed dramatically.

Not all design drift is due to the effects of time and labour shortages. Over the past three centuries changing garden fashions and philosophies have caused many topiary features and formal hedges to be recut in order to fulfil new design roles. If this transformation has not been recorded, either by written description or pictorially, it may well be difficult or even impossible to understand what the original shape and concept was. Lacking this documentary and pictorial evidence to guide conservation and restoration plans, archaeological analysis of the living evidence and its relationship to the history of the use of yew and box in gardens is often the only option. One of the first prerequisites for this course of action is to establish as accurately as possible the original planting dates.

|

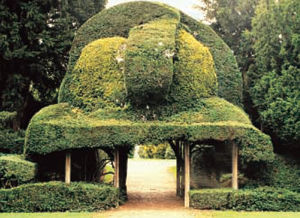

| A mature yew transported some 25 miles to its present site at Elvaston Castle, Derbyshire by William Barron the head gardener c1835 |

It also has been argued that dating is the Achilles' heel of all archaeology, and this hypothesis gains some credence when applied to calculating the age of living yew. Whilst there are a number of investigative options available, all of them are potentially flawed to varying degrees. As the earlier planting details of many historic sites are unlikely to still exist, 'desktop' surveys often rely heavily on descriptions and commentaries written long after the true origins of the gardens have been forgotten and fallacy replaces fact. Topiary and clipped hedges (of privet for example) were fashionable garden features in England during the 16th century, but at that time box and yew were not popular materials. In the 19th century however, a general but mistaken belief arose that the planting dates of many old yew hedges and topiary specimens were contemporaneous with the building of the Tudor and Jacobean mansions with which they are associated.

This application of false antiquity was reinforced by romantically connecting many of these yews to historical personalities and events, such as those allegedly planted for Mary Queen of Scots when she was held captive at Chatsworth. Those yews in reality only just post-dated Wyattville's restoration work of the early 19th century. Although box was in use in English gardens at least 50 years earlier, there is a large body of convincing evidence that common yew did not come into popular fashion until the second half of the 17th century. While original yew surviving from this period is not uncommon, it is quite possible that there isn't a single authentic extant example of an ornamental box feature planted before the 19th century in the whole country. When assessing the history of a site, claims of planting dates earlier than this should therefore be considered with some scepticism.

DATING TECHNIQUES

|

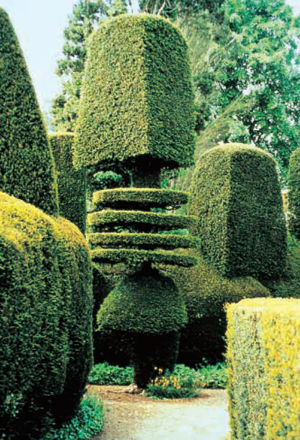

| (Above) Grafted on to an existing common yew to emphasise the form of a crown at Elvaston Castle, Derbyshire. William Barron was largely responsible for popularising this variety of the common yew from the middle of the 19th century. (Below) Yew topiary's association with Tudor and Jacobean architecture, as here at Montacute House in Somerset, is a product of 19th century fashion. The bizarre shape of this topiary is known to have remained virtually unchanged in the past 100 years, with surprisingly little 'design drift'. |

|

The most widely known and misunderstood field technique for dating yew is that of relating girth measurement to the number of years the tree has lived. Whilst this method has some value when applied to other native trees, it is extremely unreliable when applied to seed-grown common yew as genetic variations can occur which dramatically affect annual growth rates. As this has been the most popular commercial method of propagating common yew since the 17th century, the growth rates of the vast majority planted in historic gardens may vary considerably and often unpredictably. Conversely the appliance of dendrochronological dating techniques to core samples taken from living yews, using an increment borer, seems to offer a reasonable level of accuracy, as each annular ring relates to a season's growth. However, dendrochronology is not always straightforward and sometimes the uneven, almost linenfold growth of the circumference of the trunk makes it impossible to obtain core samples that give a true indication of the number of annual rings. Common yew wood is also hard and dense, so the tools have a tendency to jam and break. As a result of these difficulties and the consequent financial implications, very little of this investigative work has been done. In spite of drawbacks, however, this method does have real potential as an aid to garden archaeology.

The value of dendrochronology is illustrated by Stephen Briggs (1999) in his description of the dating of the yew tunnel at Aberglasney Gardens, Wales. For a time this ornamental feature was widely claimed to be a thousand years old. This would have made it exceptional and unique, and the historical status of the garden would have risen immeasurably. As dendrochronology has now proved that the earliest of these yews only date from the latter half of the 18th century, the Aberglasney feature is an interesting but by no means an unusual survival, especially when compared for example to the earlier, much longer and well documented yew tunnel (c 1710) at Melbourne Hall, Derbyshire.

Another dating method is by accurate identification of the species and cultivars of yew. An analysis of 17th and 18th century horticultural and botanical literature shows that, in England, the introduction and commercial availability of 'Exotic' species and cultivars of yew all post-date 1800. Any yew mentioned in early texts, except common yew, were later reclassified as belonging to other genera. The same applies to cultivars and varieties, including Irish yew, Taxus baccata 'Fastigiata', which was still thought by the great Victorian landscape designer, Loudon, to be rare in 1840. So much so, he regarded the post 1830 avenues of them at Elvaston Castle, Derbyshire, as exceptional. Concurrently, in this same remarkable garden, seed grown plants of common yew that exhibited golden or variegated foliage were being collected, planted, and vegetatively propagated under the supervision of the head gardener, William Barron. Prior to his interest in their ornamental potential they had been regarded by other gardeners as diseased and as a consequence discarded. As a result, the planting dates of golden yew found elsewhere in Britain are not likely to be much earlier than the latter half of the 19th century, although Paxton claimed to have planted six at Chatsworth in the early 1840s.

RESTORATION APPROACHES

In recent years there have been reconstructions and restorations of box and yew gardens, two notable ones being at the palace of Het Loo, Netherlands and Hampton Court Palace, England. During the pre-planning stage for the latter garden there was an extensive archaeological and historical debate on the suitable method for recreating the box parterre and the restoration or replacement of the yews. It was decided that the yews, many of which were later confirmed as the original plantings of 1702, were too large to reshape. These historically authentic trees were therefore destroyed and replaced with newly grown yew cones imported for the purpose. Apparently the decision to place accuracy before authenticity was not taken lightly, and it can be argued that the resulting restoration of the Privy Garden at Hampton Court justified the means. The loss of original living fabric, however, is at all times regrettable and should be avoided where possible.

|

| Buxus microphylla 'Faulkner' was used to recreate the geometric centrepiece of this garden at Hall Place, Beaconsfield. The variety was chosen by Anderson and Glenn because of its vigour and colour and as this photo shows, the box parterre was well established after just three seasons. The garden design was probably the work of the architect Henry Woodyer who remodelled the house in 1868 in the Queen Anne style. |

|

| The variegated colour of the new growth of this hedge at Montacute House, Somerset indicates that these plants were originally grown from seed. |

During the planning of the restoration of the Privy Garden, there was also a debate about the final choice of plant for the recreation of the parterre, and it was decided that the dwarf box, currently sold as Buxus sempervirens 'Suffruticosa', should be used. In the author's experience this is not generally a 'good doer' and in the Privy Garden it performed very badly, quickly incurring a great many losses. This poor performance is at odds with the favourable descriptions of the plant found in the horticultural literature of the early 18th century.

A possible explanation for this contradiction has resulted from the interesting research carried out on early herbarium specimens by Dr Jan Woudstra of Sheffield University. He maintains that the box-plant currently available commercially under the name of Buxus sempervirens 'Suffruticosa' is not the same dwarf box that was recommended in the 17th and early 18th centuries for use in parterres. If this is correct, the accuracy of any commercial plant material used for restorations can be called into question. In the absence of a supply of plants with a verifiable historical provenance, it is arguably just as appropriate, and certainly more honest, to use modern cultivars that are known to perform well. A typical example is the use of Buxus microphylla 'Faulkner' as a dwarf box for formal work, which Anderson and Glenn have used since 1990. Initially, the young plant displays a slightly open and loose habit, but after initial clipping it grows much tighter and holds a good sharp line. As it is a much better 'doer' than 'Suffruticosa', a parterre can be well established in about three years. In the last five years this plant has become more widely used, and a recent large-scale example may be seen in the restored Italianate Garden at Ashridge in Hertfordshire. To produce the even effect required in such a formal design, care was taken to propagate the 12,000 plants used from cutting material taken from the same genetic stock.

Superficially the conservation and restoration of box and yew topiary is a straightforward topic, but in reality it is vast and complex. Planting is rarely as ancient as people would like to believe and even the plants sold today may not be the same as those known by the same name in the past. If this article was to introduce the reader to just one notion it would be to question everything when dealing with box and yew in historic gardens.

Recommended Reading

Briggs, C Stephen 'Aberglasney: The theory, history and archaeology of a post-mediaeval landscape', Post-mediaeval Archaeology Vol 33, 1999

Thurley, Simon (ed), The Privy Garden, Hampton Court Palace, Apollo 1996

Glenn, John, 'Climate of Deceit' The Garden, Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society Vol 125 Part 1, January 2000

Glenn, John, 'What's on the Box' The Garden, Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society Vol 125 Part 9, Sept 2000

Glenn, John, 'Return to Camelot' The Garden, Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society Vol 124 Part 12, Dec 1999

Glenn, John, 'Ground Rules' The Garden, Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society Vol 124 Part 11, Nov 1999