The Cathedral Works Yard

Antony Lowe

|

|

| A temporary masons' workshop on the North Green in the 1960s (Photo: Lincoln Cathedral Works Yard Archive) |

The UK's towering gothic cathedrals form a fundamental part of our tangible heritage, continuing to draw in the religious and secular alike. Celebrated as the pinnacle of artistic, architectural and engineering achievement, these buildings are also the repository of an often untold narrative of cyclical renewal, inspiration and growth. Central to this process of rebirth is the cathedral works department.

Of the 42 Anglican cathedrals in the UK, nine retain their own dedicated body of craftspeople, including York, Lincoln, Worcester, Winchester, Salisbury, Durham, Canterbury, Exeter and Gloucester. At the heart of these works departments is a people-based enterprise, but there is no set model dictating their form or management. There are variations in structure, professional association and remit. Some have a full range of trades, whereas others are predominantly formed of stonemasons and glaziers, a natural focus given the nature of the buildings on which they work. Some work solely on the cathedral and its ancillary buildings, whereas others also take on external commercial contracts. Furthermore, in some cathedrals all the craftspeople operate as one unit, whereas in others the association is less rigidly fixed in the cathedral’s organisational structure.

|

|

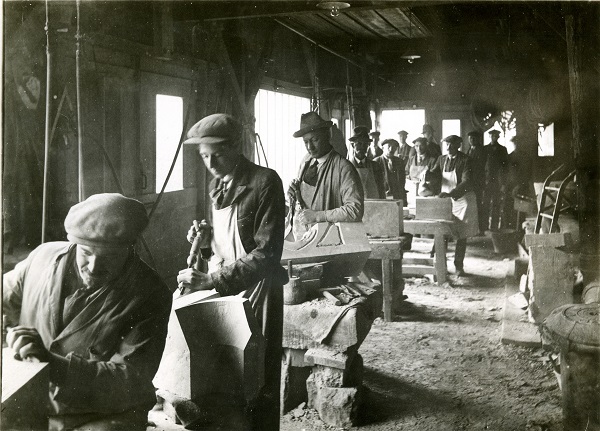

| Craftspeople working on the cathedral in the 1860s (Photo: Lincoln Cathedral Works Yard Archive) |

The common unifying factor, however, is that they all exist solely because of the cathedral. They operate from a workshop, or a series of workshops, generally clustered close to one another within the immediate environment of the cathedral itself. The archetype would be a vernacular workshop tucked away in its own corner of the cathedral close with an enclosed yard buried by unworked piles of raw stone.

Today the evolution and management of these workshops takes place against a wider narrative of declining craft skills. Reports from sector-level organisations such as Historic England have highlighted consistent gaps in the supply of craftspeople with a specific background in historic building conservation, as well as the loss of existing skills through retirement. So at a time when the ultimate sustainability of key sector skills is being questioned, it is important to recognise these sites and organisations as both historically-important and active assets so that they can be managed, developed and protected effectively.

LINCOLN CATHEDRAL

In order to understand the wider works department sector, it is worth considering one particular example in detail. Lincoln Cathedral Works Yard houses a full range of craftspeople including stonemasons, stone conservators, joiners, carpenters, lead-workers, glaziers and an archivist, as well as engineering and grounds maintenance staff. This multidisciplinary body is based on a single site situated at the north east end of the cathedral close, immediately east of the 13th-centurychapter house and the cathedral’s east end. The ‘yard’ is simultaneously a physical historic place and a body of craftspeople whose skills are valued both in terms of their modern application and their location within a historic tradition.

The heritage significance of the site is innately complex and has two main strands. On the one hand it is an architectural, archaeological and historic symbol of the past, while on the other it is a fully operational workshop whose activities have a distinct historic and cultural basis. Its work is of inherent technical value through providing the culturally sensitive expertise needed to manage this complex historic site. Furthermore, it also provides the professional conditions necessary to foster artisanal creativity, which has a much wider social meaning.

|

|

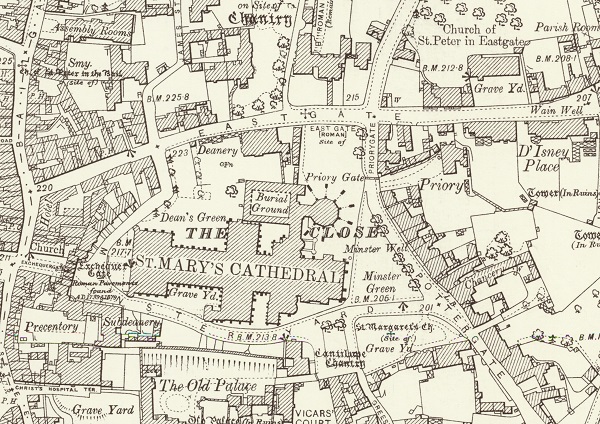

| Detail of the 1/2500 Ordnance Survey map |

The tangible remains at the workshop attest to the wider development of the city of Lincoln as a historically-rich urban tapestry and contain significant evidence for the specific development of a historic craft community on this site. Firstly, the site sits at a critical point in the historic spatial distribution of the city. It is situated immediately outside the scheduled east gate and walls of the Roman fort and later colonia of Lindum, and its significance includes potential archaeological evidence relating to its location in the settlement’s immediate extra-mural areas. The site also lies at the critical transitional space between the medieval domestic suburb of Eastgate and the city’s core ecclesiastical centre clustered around the cathedral itself. The Close Wall for example, built in the 14th century to protect the clergy from the rabble, forms the site’s southern boundary. Beyond it are the medieval close properties. On the site itself are two administrative buildings which date from the 17th century, possibly earlier, although substantially altered with Georgian, Victorian and early Edwardian façades. The buildings were historically used as a bakery, an inn and lodgings before the works department moved to the site in the late 1880s.

Beyond these broader archaeological and standing remains, the site also includes infrastructure specific to the development of the site as a craft base focused on the cathedral. On the site is a series of late Victorian vernacular workshops, altered and expanded throughout the 20th century. These workshops provide a physical locus to the craft tradition to which many of the craftspeople at the site feel they belong, knowing that the skills they practise here have been used on this site for over a century. This communal sense of continuity and tradition is supplemented by the works yard archive, which includes historic photos of masons and other craftspeople working on the cathedral.

|

|

| Lincoln Cathedral Works Yard with administrative buildings to the front and workshops behind (Photo: Antony Lowe) |

Woven into the fabric of these workshops are historic pieces of machinery, including a 1920s compressor that has chugged away here for nearly 100 years, providing a constant background heartbeat. The site includes a large collections store with relic sculpture taken from the cathedral during years of conservation work, including internationally significant examples from the medieval period. There is also a series of hidden underground shafts used to store precious stained glass during the second world war to protect it from air raids.

These buildings and collections also have a unique visual and emotive impact in relation to the surrounding context, which includes fine examples of historic domestic and ecclesiastical architecture. These contrasting uses add to the rich narrative of both the area’s historic growth and the specific lifecycle of the cathedral itself.

In terms of its tangible remains alone, the Lincoln Cathedral Works Yard is significant because it is indicative of the development of Lincoln as a rich historic multiphase settlement from its earliest period. It also exemplifies the subsequent development of domestic, commercial and light industrial activities with close associations to the growth of the cathedral as a distinct and complex space within the wider urban milieu.

The tangible remains, however, are only one part of the story. There are numerous ways to frame the intangible elements of the site but two of the most evident are the distinct ways of working associated with it and the value of the end-product.

There are ways of doing things at the site that have intrinsic value to the people who work there. In particular there is an evident importance placed on working in very close proximity to the cathedral itself, as craftspeople stretching back over 100 years have done. Furthermore, the remit of the yard enables its craftspeople to work on a single building across a significant period of time, as well as creating a very specific multidisciplinary trade network with one common goal. This way of doing things has an evident practical purpose, logistics, but it also facilitates the development of a very specific affinity between craftsperson and building and creates a profound place-based knowledge that is vital for the effective continual renewal of the building. This relies not just on being a skilled craftsperson, but is enhanced by developing an intellectual connection with the building over a long period of time. This allows the growth of a very specific type of intelligence, one centred on a unique place-based artisanal understanding.

| A 2011 sculpture on the south transept warning against the sin of greed (Photo: Antony Lowe) |

There is also a much broader social value associated with work at the site and with traditional trades and craft skills in general, although it can be difficult to pin down why people attribute value to them. Specifically, the premium placed on craft skills draws on broader concepts of the importance of culture and art for social wellbeing. This social value rests, quite rightly, on a belief that skills and techniques that rely on human skill and allow the practitioner to retain control over the production and creation process should be perpetuated. While not necessarily unique to this type of site, there is a real sense that the works yard is a centre of human creativity that is rooted in a deeply historic and identifiable linear progression of techniques and communities.

A tour of the cathedral exterior highlights several recent and modern sculptures which, while responding to the contexts of the cathedral and its message, are not simply reproductions. These include sculptures warning of modern greed, commemorating the fox-hunting ban, and one which immortalises the face of a long-serving employee of the works yard, all carved and placed on the south transept in 2011. The important consideration here is that the work is not just a process of re-creation (though that in itself may have profound value) but also one of creation, and this has a more ephemeral value closely associated with satisfying what art historian Alois Riegl called the innate human ‘will to art’. This importance extends far beyond the purely practical and has connotations beyond the management of one building.

PROTECTING THE INTANGIBLE

So, in cathedral works yards such as Lincoln we have both significant tangible and intangible remains. That leaves the question of management and how we can protect these sites into the future. There are two key

problems to consider. Firstly, there is the problem of museumification. It is important to avoid thinking of the body of craftspeople and the infrastructure as static monuments. The works yard is not simply a crumbling set of stone walls that must be propped up, but the work space of a body of professional people which needs to adapt, grow and respond to innovations in techniques, processes and working practices.

Managing the site as something which is dynamic rather than static, and focusing understanding of its significance more on the people and their methods highlights a very distinct and unique historic value. It was, after all, the medieval cathedral building sites, usually only a physical location for the duration of construction, that provided the most significant chance for multiple trades to come together and innovate. In this environment they were able to develop the new methods, theories and techniques necessary to plan and build increasingly innovative feats of architecture, art and engineering. It is important to consider the works yard not as a simple representation of traditional craft skills, but in fact as the next generation in a historically valuable but technically progressive lineage. It is a body that has important historic roots but in fact has always been the focal point around which action, innovation and architectural development are wrought.

There is, in fostering innovation, an inherent and very real historic meaning. In the 1990s, for example, the yard at Lincoln became a locus around which a wide range of art historians and craftspeople converged to approach the unprecedented re-creation of the north run of the romanesque frieze on the cathedral’s west end, when the original became too damaged to remain in situ. This convergence was akin to the melding of minds which was so integral to the original cathedral building process.

This, however, raises a second problem. Heritage management in this country has yet to fully address the importance of intangible heritage and how it can be managed within the wider significance package. While intangible heritage is, in some ways, considered as part of broader concepts such as communal value (which addresses social importance), this by no means encompasses its potential and full implications. Until legislation and heritage policy consider the full implications of intangible heritage, it is going to be very difficult to manage the works yard as a heritage asset. At the moment we either have to consider it as a tangible historic site, which to some extent limits its ability to grow by failing to consider the weighted importance of physical fabric to communal, people-based value and tradition, or consider it only as a modern workplace, which risks damaging its historic importance.

A more productive, and accurate, way of considering a cathedral works yard is as one which combines interrelated elements of both tangible and intangible heritage. The distinct physical elements of the site are important as symbols of both the broader historic development of the ecclesiastical landscape and its secular surroundings, and the specific growth of its craft community. However, there is also a much wider use and social value attached to the way in which the yard’s craft community has been afforded the necessary scope to develop a particular, place-specific cultural intelligence and to evolve as a centre of artistry and creative innovation.

| North run of the the romanesque frieze on Lincoln Cathedral's west front: these modern replica carvings replace the badly deteriorated 12th-century originals, which have been conserved and mounted as an exhibitin in the Morning Chapel. (Photo: Antony Lowe) |

FURTHER INFORMATION

PS Barnwell et al (eds), The Vernacular Workshop: From Craft to Industry 14001900, CBA, York, 2004

RK Blundel and DJ Smith, ‘Reinventing Artisanal Knowledge and Practice: A Critical Review of Innovation in a CraftbasedIndustry’, Prometheus, 31:1, 2013

M Jones et al (eds), The City by the Pool: Assessing the Archaeology of the City of Lincoln, Oxbow Books, Oxford, 2003

S Jones and T Yarrow, ‘Crafting Authenticity: An Ethnography of Conservation Practice’, Journal of Material Culture, 18:1, 2013

S Jones and T Yarrow, ‘Stone is Stone: Engagement and Detachment in the Craft of Conservation Masonry’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 20:2, 2014

A Riegl, ‘The Modern Cult of Monuments its Essence and its Development’, 1903, in NS Price et al (eds), Historical and Philosophical Issues in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage, Getty Conservation Institute, 1996

R Sennet, The Craftsman, Penguin, London, 2009

D Turnbull, Masons, Tricksters and Cartographers, Harwood Academic, Amsterdam, 2000

M Varutti, ‘Crafting Heritage: Artisans and the Making of Indigenous Heritage in Contemporary Taiwan’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 21:10, 2015