Burials in Churches

Ruth Nugent

Memorials painted onto walls were an alternative to sculptures, although fewer survive and some maybe retrospective memorials. This example is at St Alban’s Cathedral.

MANY CHURCHES have human remains interred within the building, particularly if built before 1850, and in some cases a complex network of burials may lie beneath their floors. It is therefore important that everyone involved in church conservation is aware of the changing practices that occurred over the years, as this will inform our understanding of the history of the building and the causes of defects in the fabric that may arise. It may also help us to avoid the unintended consequences of ill-informed interventions. This brief overview outlines general spatial patterns of burials and monuments inside churches in broadly chronological order, summarising the key periods and events which have caused so many bodies, tombs and memorials to be relocated or removed entirely.

11th and 12th CENTURIES

Until the 11th century, only saints, royals and clergy were usually buried inside churches, with most people interred in minster and parish churchyards. However, during the 10th to 12th centuries, wealthy landowners began building private chapels which gradually led to the development of their own cemeteries.

It was the Normans who popularised monastery burials in the 12th century to benefit from the monks' constant prayers on behalf of the dead, a service which minsters and parish churches were rarely able to offer. Monasteries, especially high status abbeys, remained the most prestigious indoor burial sites until the late 13th century, with some elite individuals being exhumed and relocated indoors, in a bid to underline their status. High ranking lay people, abbots, senior clergy, founders, patrons and donors of large gifts of land or money were usually buried in the monastery’s chapter house or cloisters, as burial inside the monastic church was limited to saints and exceptional individuals.

Cloister burials in particular created a surge in grave slabs decorated with a simple cross, and for the elite, effigy tombs appeared in the mid- 12th century. Often these were empty with the burial beneath the floor. Monumental brasses began to be used for bishops’ burials in the 1270s–1280s, and where an effigy tomb was deemed a physical impediment, brasses could be inserted into processional routes or next to shrines. Unfortunately, few of these early brasses now survive.

13th and 14th CENTURIES

Despite a few late 12th century examples, lay burials did not really move indoors until the mid-13th century. While the chancel was reserved for clergy burials, parishioners could be buried in the nave, transepts and side-chapels. In the 1320s–1330s, the gentry began placing their tombs inside recesses or wall niches within the church. An interesting development in the 14th century saw parish churches and cathedrals allowing individuals and their families to build private chantry chapels inside the church, a proposition which subsequently became more popular than indoor monastery interments. Nonetheless, the lower classes continued to be buried in churchyards and lay burial inside a church was still relatively rare in Britain.

A fashion for wooden effigies, plastered with gesso and painted in imitation of stone, took hold amongst the highest ranking clergy, aristocrats and gentry in the late 13th and early 14th centuries only to be superseded by the more lustrous alabaster in the mid- 14th century. However, the Black Death caused a significant drop in all monument production during the 1350s–1360s, while burials rapidly increased.

15th CENTURY Despite pressure from influential citizens, most cathedrals and abbeys continued to reserve certain spaces for ecclesiastical burials only, such as the chancel. In particular, a tomb on the north side of the high altar was an exceptional burial location because it could be used as an Easter Sepulchre during Holy Week, attracting huge attention during this important time. Yet, by the mid-15th century the nobility and gentry had gained burial rights in the chancel too and were trying to encroach further on exclusive burial spaces.

In contrast, burials of the lower classes were dispersed around guild chapels, nave aisles, near popular devotional images or minor altars in the nave and transepts. Some asked to be interred where they had sat in the nave or near loved ones while others were added to lines of burials along processional pathways inside the church.

However, identifying middling and lower class burials in church buildings is difficult. They often commissioned small floor memorials, and many were placed in cramped urban churches where floor space was at a premium. High traffic has eroded the inscriptions, leading to some being mistaken for paving stones and reused as flooring, or the high turnover of burials meant they were replaced with someone else’s. As early as 1427, an anonymous monk at St Alban’s Abbey lamented over precisely these issues.

16th CENTURY

The Dissolution of the Shrines under Henry VIII began in the 1520s, dismantling saints’ shrines and reburying or discarding saints’ remains. During the religious turbulence of the Reformation and state enforced iconoclasm of the dead under Elizabeth I, some families privately reburied their ancestors elsewhere for fear of desecration, sometimes leaving empty tombs and memorials behind.

Before the 16th century, mortuary monuments were largely horizontal. Now, vertical space was used on an unprecedented scale through wall memorials, upright effigies, busts and memorial windows. This relieved pressure on floor space from accrued tombs and the increased number and size of church pews. Burial locations largely followed the same spatial arrangements as before and defunct chantry chapels were sometimes repurposed as family burial vaults or even storage. Lady Mohun’s chantry chapel built in c1375 at Canterbury Cathedral was still being used as a lumber store by the 18th century, severely damaging her tomb canopy.

Some wall memorials were created out of existing floor memorials to save them from destructive rebuilding work, to relocate them near other family wall memorials or to rescue them from wear and tear. This practice was to continue throughout the following centuries. It is possible to identify these repositioned memorials by the presence of a Lewis hole (a notch for a tool used to lift heavy blocks of stone) or large chips around the edges made by levers and crowbars when it was lifted. Also, secondary features may have been added to transform the floor memorial into a wall feature, such as a tiny plinth to support the base or a loop added to hang it. In contrast, original wall memorials were usually screwed into the wall, not hung from a single point. Another clue may be an inscription referring to the burial ‘Underneath’, ‘Beneath’ or ‘Below’, but confusingly, similar wording can also be found on wall memorials erected in later centuries as they became increasingly distanced from their burials.

Although around 4,000 monumental brasses survive in England, they were often stripped from floor memorials in the mid-late 16th century, either to engrave the reverse for a new memorial or for resale as scrap. What may remain is the ‘matrix’ which the brass was fixed to.

17th and 18th CENTURIES

An unofficial memorial graffitied on a cloister bench in Canterbury Cathedral: graffiti like this on church monuments peaked in the 17th to 19th centuries, but graffiti can also demarcate where monuments have been removed. (Photo: Ruth Nugent)

By the 17th and 18th centuries, following decades of unrepaired iconoclasm, many churches were suffering from serious neglect and damage but were often too cash poor to pay for repairs. Many cloisters had lost their windows through neglect, vandalism, looting, English Civil War destruction and other local crises. This exposed cloister burials and memorials to weathering and even flooding. Churchyards, most notably at Chester Cathedral, were even used as local rubbish dumps, which can explain butchered animal bones appearing in later churchyard burials. Clergy were also recorded requesting burial at their better preserved parish churches rather than their cathedrals which had endured the harshest treatment.

|

||

|

||

|

||

|

||

| Displaced monuments in the cloisters of Chester Cathedral |

Reflooring was often a priority when money became available because as bodies and wooden grave furniture decayed, surrounding soil collapsed into the void, causing subsidence. Since naves and transepts had the densest burial populations, they often needed immediate attention. This situation had a direct impact on existing memorials. New floors commonly incorporated old grave slabs turned face down. In addition, floor memorials in poor condition were sometimes broken up for gravel and used to line pathways in churchyards or repair holes in churchyard walls. As a consequence, many burials lost their grave covers and are now hidden beneath plain paving stones.

Soldiers stationed at cathedrals during the English Civil War in the 1640s were regularly accused of desecrating graves. While allegations were often exaggerated for propaganda purposes, excavations at Canterbury Cathedral in 1993 revealed nave burials had indeed been looted during this period and human remains dumped in a pit beneath the nave. Similar ‘dumps’ of human remains have been found in other churches and cathedrals dating to the 17th–18th centuries, suggesting that many burials were heavily disturbed by Civil War activity and/or reflooring programmes.

19th CENTURY

‘Restoration’ campaigns by the Victorians, especially in cathedrals, removed many older tombs, graves and memorials too damaged to salvage, awkwardly placed, or that didn’t fit the new decorative schema. Also, as at Chester Cathedral, building contractors were occasionally allowed to keep grave markers as part payment and some may have found their way into other local buildings. During restorations, rare survivals of medieval saints' shrines, which had been dismantled and buried during the Reformation, were sometimes discovered and reassembled. Examples of this can be seen at Chester Cathedral (St Werburgh’s shrine); St Alban’s Cathedral (St Alban and St Amphibalus’ shrines) and Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford (St Frideswide's shrine).

The Burial Acts of the 1850s banned intramural (interior) church burials for reasons of space and hygiene. This is generally still the case today, albeit with some exceptions. With the rise of public or ‘garden’ cemeteries and new crematoriums in the later 19th century, many people were now commemorated with a church wall memorial but buried at an entirely different location. Although archbishops, bishops, deans, (and their spouses and children in some cases) could apply for intramural interments, some chose burial (including cremation burial) in the churchyard or cloister garth, with a memorial (anything from a small plaque to an empty tomb) inside the cathedral. Victorian effigy tombs often copied or simplified medieval versions but with increasingly realistic portraiture of the deceased.

20th and 21st CENTURIES

Interior commemoration in the 20th and 21st centuries has been pragmatic, using repairs, remodelling, new fixtures, windows and furniture as alternatives to traditional monuments. Furthermore, as modern interior monuments are no longer expected to cover or even mark a grave, they do not need to be a certain size and shape. Ships’ bells, aeroplane propellers, mosaics and numerous artefacts and art works are among the many new types of memorials introduced in the 20th and 21st centuries. New styles, such as transparent memorials at Exeter Cathedral, have appeared. Cremated remains of eligible clergy have also been placed within stone benches inside some church buildings creating a new use for ancient features.

LOCATING BURIALS TODAY

Multiple disturbances to burials and mortuary monuments have left many churches like a hall of mirrors. Some church and churchyard tombs may also be spolia – that is to say, comprised of different pieces of tombs, memorials, and even altar tables and pieces of shrines, as a way of conserving fragments of dismantled monuments. They may even have no historical relation to any burials they claim to mark.

The function of tombs could alter over time, being repurposed as cenotaphs or converted into war memorials. Their appearance could also significantly change as graves were looted, brasses stripped and grave slabs were displaced. And tombs could migrate, with those originally designed for churchyards being relocated indoors while others staying in their original position find themselves enclosed by later church extensions. Similarly, interior tombs could be moved to the churchyard when space was scarce or the tomb in poor condition or unwanted.

Archival evidence can be equally frustrating. Burial registers (made mandatory in 1538) did not need to record burial locations, and if they did, entries were often vague (such as: ‘north’, ‘by the door’, or just ‘nave’). Wills might record a requested burial location, but there was no guarantee this would be provided, and even less certainty they would not be moved later. However, monument catalogues compiled by a church or an antiquarian may indicate if tombs or burials have moved.

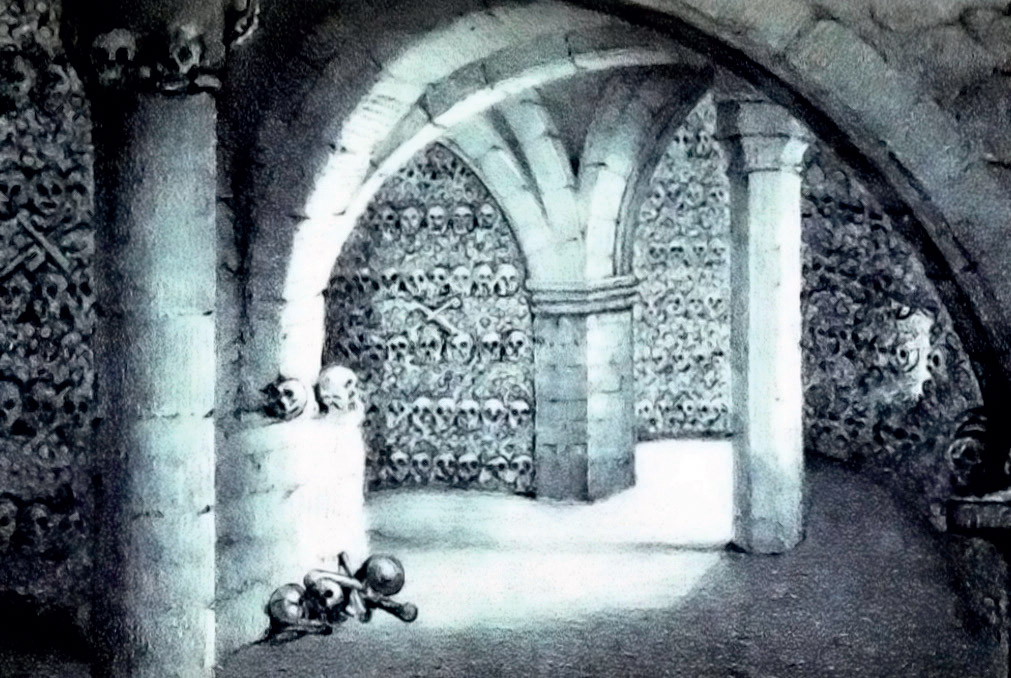

Compounding this further are charnel deposits from all periods, some representing hundreds or even thousands of individuals exhumed ahead of building work or to make room for new interments inside churches and churchyards. For example, in 1512 thousands of individuals were exhumed from Ripon Cathedral’s churchyard (then a minster) ahead of work to widen the nave. The bones filled the Norman-era crypt and were stacked behind a wall east of the choir too. More bones lay below the crypt floor to a depth of 4ft [1.2m], and even more had to be reburied later in the churchyard. Like many church charnel collections, it was likely locked away or blocked up in the late 16th or 17th centuries, then ‘rediscovered’ in the late 18th and 19th centuries. The charnel was thinned out, retaining long bones and almost 10,000 skulls and rearranged into a display in 1843, becoming a popular visitor attraction. It was subsequently closed to the public by local authorities and the bones reburied in the churchyard in 1865–7, reflecting increasing distaste for unburied human remains by the later 19th century. But mass pits of fragmented human remains are likely awaiting discovery under many floors and in numerous churchyards.

|

||

| The ‘Bone-House’ at Ripon Cathedral in 1838, as illustrated in The Tourist’s Guide: being the concise history and description of Ripon (1838, 2nd ed, Anon) |

Repairs and restorations unearthed many grave markers and stone coffins which may still lack a ‘home’. Exeter Cathedral relocated some medieval grave slabs to the refectory as freestanding sculpture. Chester Cathedral installed loose grave markers and a stone sarcophagus in their cloisters (newly glazed in the 1920s) and inserted some into cloister walls. However, some pieces may be wedged behind tombs or pillars, propping open doors or filling up storerooms. How unearthed burial markers will be managed should also be considered before potential burials are disturbed.

Managing historic church burials and monuments is complex and anticipating what may or may not be found during development work is often guesswork. However, a new research and engagement programme called ‘The Human Remains’ aims to reduce the confusion. By working with churches to identify local, regional, and national patterns and histories of burial disturbance in England, Scotland and Wales, it can inform planning and maintenance strategies across all historic sites with religious burials, including cathedrals, churches, castles, stately homes, converted churches and ruined religious houses. Launched in November 2019 and funded by the UKRI Future Leader’s Fellowship scheme for seven years, it demonstrates substantial government investment in church burial environments. By learning from these intricate histories of burial and disturbance, we may offer those buried in our churches a more stable future.