In Trust

Jonathan Taylor

|

|

| Cromarty East Church, Ross-shire: this church was described by John Hume, former principal inspector of buildings for Historic Scotland, as 'unquestionably one of the finest 18th-century parish churches in Scotland'. |

Most historic places of worship are kept open and maintained by the church authorities which own them, with some help from the state and from other charitable bodies. It falls to the incumbent, the churchwardens and the congregation to find the necessary funds to pay for their upkeep and to cope when disasters arise. But what happens when the congregation is too small to cope and can no longer afford to maintain its building?

Of the top ten tourist attractions in Britain, six are cathedrals. Visiting historic buildings is the second most popular recreational activity after shopping, and it is not surprising to find that historic cathedrals and churches are the most numerous, most accessible and the most visited of all. Their importance is unquestionable, not only to those who live nearby and who worship in them, but also to the heritage of this country as a whole, and economically, for their role in tourism.

Who can fail to be moved by lifting the heavy iron latch of a medieval parish church and the slow creaking swing of its solid oak door? Entering an ancient church, whether in a city or the countryside is a moment of great anticipation. The transition from outside to inside, from bright grassy churchyard to cool dark interior is full of mystery and contrasts. No other architecture or experience is quite like this. All the details are unfamiliar elsewhere; the materials used, their texture and richness, their colour, scale and smell. The few moments it takes for the eye to become accustomed to the light intensifies the experience, since the first things you see on entering the dark interior are close by, as if you were passing through a tunnel; the worn paving slabs, wood or tiles, the first pew and perhaps the hymn books waiting to be picked up. Then the scale of the interior is slowly revealed, turning the act of entering the building into an event in itself, filled with drama.

The interiors of almost all places of worship – churches, chapels and cathedrals – have one thing in common; they are all inward looking. The windows are raised above eye-level, so that they let light into the interior without giving views outside, and often they are entirely obscured by stained glass. The architecture is designed to reinforce quiet contemplation in a space apart from the world beyond. It is particularly suited to the function; the worship of God. It is not readily adapted for any other use.

For those who are religious, including the many who only ever attend church for Christenings, weddings and funerals, these buildings have perhaps the greatest significance. Nevertheless, historic churches, cathedrals and other places of worship draw visitors from across society, irrespective of creed and class. The visitor does not have to share the religion to enjoy the architecture.

It is perhaps a sign of the Government’s recognition for the importance of these buildings to the community as a whole that it focuses some grant aid on the repair of churches, and has, in effect, introduced a reduced rate of VAT on repairs through a grant scheme. However, the burden of responsibility remains firmly with the congregation and the local community to fund repair and conservation work and to cope when disasters arise. But what happens when a dwindling congregation finds that it can no longer justify the expense of running, maintaining and repairing a building that is far too large for their needs and it becomes redundant? The options are as follows:

|

||

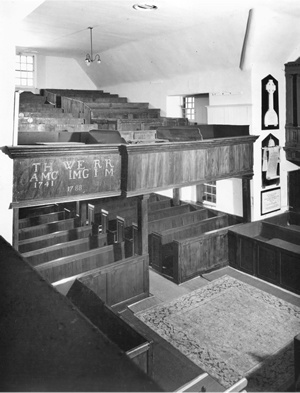

| Cromarty East Church in Ross-shire: interior view showing the north gallery, which was known as the 'poor loft' as money from the rental of the pews was given to the poor of the parish (Photo: RCAHMS) |

Dereliction and demolition

All too often historic

places of worship are abandoned and left derelict, pending their sale

or demolition, creating a soft target for vandalism and theft. Lead may

be stripped from the roofs, fittings may be stolen, windows smashed and

in the worst case, the building may ultimately be gutted by fire. Even

at this point it may be possible to rescue the building, as in the case

of St Elizabeth’s, Gorton, Greater Manchester, but demolition is the more

likely outcome.

Sale – usually for conversion

The

place of worship may be put on the market. However, it is rare to find

a new owner who wishes to keep the building as a place of worship, and

these buildings are notoriously difficult to adapt for new uses. Conversion

to housing, in particular, almost invariably requires the subdivision

of the main spaces, window alterations and often the introduction of a

large number of roof lights to let in more light and to provide views

out. All the fittings are usually stripped out, including stained glass,

organ, pews and so forth, rough walls are usually plastered over, and

the original character is obliterated.

Church trust ownership

Over

the past few decades a few places of worship have been looked after by

a growing number of charitable bodies whose purpose is to look after the

most important historic places of worship which would otherwise be redundant,

and to keep them open to visitors and for occasional worship wherever

possible. Five of these organisations operate nationally. Of these, the

Friends of Friendless Churches is the oldest, having been set up in 1957,

followed by the Churches Conservation Trust which was founded by the Church

of England in 1969 specifically to look after its own redundant churches.

In 1993 the Historic Chapels Trust was established to deal with non-conformist

chapels in England and Wales, and two more trusts have now been established

to look after buildings in Scotland and Wales.

In addition to these national organisations, there are a number of trusts dotted across the country which are responsible for caring for churches locally, such as the Norwich Historic Churches Trust.

THE

FRIENDS OF FRIENDLESS CHURCHES (Follow link for details)

This

society was established in 1957 by Ivor Bulmer-Thomas and has since saved

over a hundred churches from destruction and accepted the direct responsibility

for 31 churches or chapels in England and Wales. Its key objective is

to secure the preservation of churches and chapels of any denomination

within the UK for public access and the benefit of the nation. The buildings

are maintained ‘for the advancement of the Christian religion’, and in

most cases occasional services are held in them, but they may also be

used for other charitable purposes agreed by the society.

Although the society is currently considering a church on the Isle of Man, most new vestings are in Wales where the society is now recognised as the equivalent of the Churches Conservation Trust. It therefore receives 70 per cent funding from the state through Cadw and 30 per cent from the Church in Wales.

THE

CHURCHES CONSERVATION TRUST (Follow link for details)

Established

in 1969 by the Church of England, the trust looks after redundant Church

of England churches only. It is currently responsible for 329 churches,

most of which are Grade I or II* and most are open daily. Some of its

churches host events such as concerts, talks, exhibitions and flower festivals.

Many of the churches also organise occasional services which are advertised

locally.

The Churches Conservation Trust (formerly The Redundant Churches Fund), a registered charity, receives most of its funding from the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and from the Church Commissioners.

THE

HISTORIC CHAPELS TRUST (Follow link for details)

This

trust was founded in 1993 to look after English redundant chapels from

all denominations other than the Anglican Church. Its buildings are either

of outstanding historical or architectural interest, with most of them

being listed as either Grade I or Grade II*. The chapels’ contents and

burial grounds are also repaired and maintained by the Trust. The HCT’s

remit embraces Nonconformist chapels, Roman Catholic churches, synagogues

and private Anglican chapels.

The Trust’s chapels are frequently opened to visitors and used to host a wide range of suitable events. Alternative uses may sometimes be agreed, provided they do not involve unsympathetic alterations to the building. The Trust’s costs are currently supported by a 70 per cent grant from English Heritage, which also contributes to the cost of repairing chapels.

Sixteen

chapels are owned by the Trust. Recent acquisitions include Wallasey Unitarian

church. The repair and conservation of the Unitarian Church at Todmorden

was featured in the 1996 edition of Historic Churches.

THE SCOTTISH REDUNDANT CHURCHES TRUST (Follow link for details)

Founded in 1996, this trust was established to secure the survival of outstanding churches of all denominations where they are threatened with closure. By acquiring these churches and by conserving them intact as historic buildings, the Trust aims to preserve a valuable part of Scotland’s ecclesiastical heritage for the future.

There are now four properties throughout Scotland belonging to the Trust: St Peter’s Church in Orkney (1998), Cromarty East Church in Ross-shire (illustrated above, 1998), Pettinain Church in Lanarkshire (2000) and Tibbermore Church in Perthshire (2001). The first major conservation project undertaken by the Trust is St Peter’s Church at Orkney, which is nearing completion following six months of extensive repair work. This building was on the Buildings at Risk Register of the Scottish Civic Trust and rescued with the aid of £250,000 in grants. It is scheduled to reopen in 2003.

WELSH

RELIGIOUS BUILDINGS TRUST (Follow link for details)

The

Trust was established following the publication of the Cadw-sponsored

report Redundant historic chapels in Wales in September 1996, which suggested

the formation of an independent charitable trust to hold redundant historic

chapels of significance for future generations and to be an advisory body

information source.

The aim of the Trust is to promote and advance the religious and associated heritage of Wales by acquiring and conserving important religious buildings which have become redundant. To avoid duplicating the work of The Friends of Friendless Churches, those of the Church in Wales are excluded. Its first acquisition is likely to be Hen Dþ Cwrdd, a 19th century Unitarian chapel at Trecynon, Aberdare which is redundant and urgently needs the Trust’s help.

ST

GEORGE'S GERMAN LUTHERAN CHURCH

Some

of the churches and chapels taken on by these trusts are already in a

ruined state, such as the Church of the Assumption of Our Lady, near Aylesbury,

but most are acquired as they become redundant, or shortly afterwards.

In this respect St George’s German Lutheran Church, Tower Hamlets, London

is typical. This church has survived virtually unchanged since it was

built in 1762-3, and it is now the oldest German building in Britain.

It was founded by Dederich Beckmann, a wealthy sugar boiler and the cousin

of its first pastor. For over 150 years its congregation consisted of

generations of German immigrants who worked in sugar refineries in the

East End. The church closed in 1996 when the congregation decided to merge

with a neighbouring church. The property was acquired by the Trust in

1999.

|

|

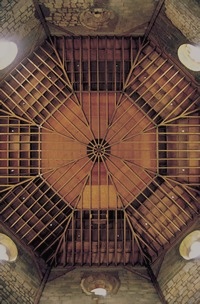

| The Church of the Assumption of Our Lady: this mid 18th-century church in the grounds of Hartwell House near Aylesbury was rescued by the Churches Conservation Trust in 2001. The detail below right shows the new roof, which was designed by Wright Consulting Engineers. |

The church is situated in Alie Street and has a brick facade with a Venetian window at the ground level, a Diocletian window above and a crowning pediment. This was once surmounted by an elaborate bellcote with a cupola and weathervane. Inside, St George’s retains many of its original furnishings and features, including a complete set of ground floor and gallery pews and a high, central double-decker pulpit. The coat of arms of King George III hangs above the communion table – the only German church to have a royal coat of arms.

THE

CHURCH OF THE ASSUMPTION OF OUR LADY

Dating

from the mid 18th century, The Church of the Assumption of Our Lady (left) is

situated in the well-kept grounds of Hartwell House at Hartwell near Aylesbury,

Buckinghamshire. It had lost its original roof during the 1950s when a

combination of poor maintenance and the failure of parapet gutters built

over the roof structure led to the disintegration of the supporting timbers.

Major repairs were required to prevent the loss of the rest of the building.

In July 1976 the building was vested in the Churches Conservation Trust.

Work eventually began in 2001 when a new roof of Westmoreland slate was constructed. In elevation, the design followed the lines of the original, but there the similarity ends. The new roof structure had to be designed to avoid imposing lateral loads on the already weakened walls, and site access prohibited the use of a crane. The solution, which was designed by Wright Consulting Engineers, introduced a simple, modern roof structure using traditional materials in keeping with the original architecture. This involves a self-supporting frame, only requiring vertical stability from the masonry external envelope, and the ceiling structure is suspended from the roof structure via stainless steel hangers.

|

The result was awarded a commendation by the Institution of Structural Engineers in 2002 for its innovative structural solution.

OTHER

TYPES OF CHURCH TRUST

In

addition to the above trusts, all of which have taken ownership of historic

places of worship, there are a number of other trusts with similar sounding

names but which do not own churches or chapels, but do help historic places

of worship which are still in use by giving grants, advice or help in

other ways. These include the Historic Churches Preservation Trust and

the Church Buildings Renewal Trust based in Glasgow.

The Historic Churches Preservation Trust, which was set up to help the countless churches damaged in the Second World War, is particularly important as it operates nationally, offering grants for essential repair work [Editor's note: the HCPT was relaunched as The National Churches Trust in June 2007].

It also administers the King of Prussia Awards – a Gold Medal was first awarded by Freidrich Wilhelm IV, King of Prussia in 1857 in recognition of the work of the Incorporated Church Building Society (ICBS). Since 1977 a Gold Medal has been awarded in May each year to the architect or chartered surveyor of a scheme of repair to a church or chapel in England and Wales.