Cleaning Historic Stained Glass Windows

Léonie Seliger

|

|

| Mould growth |

Stained glass and leaded windows in churches do not normally require regular cleaning. There are, however, reasons why cleaning may become necessary. This article provides an introduction to the types of soiling found on the internal and external faces of stained glass, when and how to clean them safely and sympathetically, and the kinds of damage that can result from inappropriate cleaning.

SURFACE DEPOSITS

Surface deposits and accretions on windows come in a great variety of forms, on both internal and external surfaces.

On the external surface

Rainwater running down the outside of the

building and onto the windows slowly deposits

particles of the surrounding materials onto the

glass surfaces. These deposits include limescale

from render, mortar and limestone; and rust

from ironwork. Over time they form a thin but

very tough patina. On stained glass windows

this usually just mellows the intensity of the

sunlight passing through the glass but on clear

windows a dense patina can be quite intrusive.

Airborne particles can attach themselves to the glass surface and to the leads. Heavy traffic or industrial pollution can deposit thick crusts, which are most visible in those areas that are protected from direct rain, such as at the top of a lancet, in small tracery panels or under a horizontal bar. These crusts can be quite loose and flaky, but they can also be extremely hard. Tree sap may regularly coat a window in sticky droplets, which then allow dust to adhere to the glass. Over time, this can result in similar crusts.

Bird guano is another frequent nuisance. Because there are serious health risks associated with bird guano, it should only be removed by trained people who are aware of the risks and use the appropriate safety equipment.

Organic growth such as algae and lichens (top right) can also be found on the outside of windows.

On the internal surface

Even if a window is not leaking, water in

the form of condensation will regularly run

down the inside surface and can create thick

limescale deposits (facing page). Soot from

decades of burning candles can gradually

cause window glass to darken.

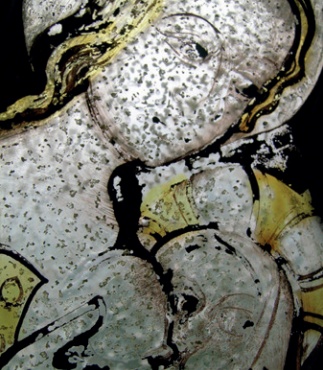

Algae, fungi and moulds (facing page)

are more often found on the inside of a

window, as there they have a regular supply

of condensation water but are not washed

away by rain.

CORROSION OF MEDIEVAL GLASS

|

|

| Lichens on the external surface of medieval stained glass | |

|

|

| Limescale deposits |

Medieval glass will often show corrosion damage and weathering crusts on the inside as well as the outside.

On medieval glass, corrosion processes can result in ‘weathering crusts’. These can cover entire pieces evenly with brownish or whitish crusts but they also often erupt from distinct pits, covering the surface in white spots (above). These crusts are the result of a chemical interaction between the glass and the atmosphere under the influence of water. Underneath the weathering crusts the medieval glass surface is always severely damaged and very fragile.

DAMAGE CAUSED BY DEPOSITS

Some glass types are more prone to damage than others and medieval glass is particularly vulnerable. Some deposits can be harmful to the glass while others are not. Patina and some hard crusts, although they can be unsightly, are unlikely to cause damage to the underlying glass.

Soft deposits that attract and hold water on the surface, and particularly organic growth, can actively damage the glass by keeping it damp. Organic growth often has acidic metabolic by-products and, over time, can trigger corrosion damage even on post-medieval glass and paint.

Painted decoration is particularly at risk. Glass paint is similar to a pottery glaze and is fused to the glass surface in a kiln before the window is assembled. Windows of all ages can have problems with poorly fired, damaged or decaying glass paint (above and right), and it takes an expert to tell whether or not the paint is stable.

HOW TO CLEAN STAINED GLASS

Assessing the condition of glass and painted decoration and advising on a suitable cleaning method should always be carried out by an accredited conservator, even if the actual cleaning can in some cases be carried out by non-professionals. Even plain unpainted glass may be very old and can be damaged by the wrong choice of cleaning method or by unskilled hands.

Church windows consist of a mosaic of small glass pieces which are held together with lead profiles and weather-proofed with a grout. They are typically inserted into stone surrounds and strengthened against wind pressure with horizontal metal bars that are inserted into the surrounding stonework and attached to the windows with wire.

The complicated construction of church windows means that they have to be cleaned by hand, piece by piece. Depending on the nature of the deposits, cleaning can be time consuming and potentially damaging, and may need to be carried out by skilled professionals. In some cases, gentle and comparatively quick cleaning with cotton wool and distilled water can remove simple loose dirt and bring a window back to its original splendour. In other cases, cleaning may be impossible, or can only be done under a microscope in a conservation studio.

|

|

|

| Typical corrosion damage to the exterior face of a medieval stained glass window | Loose flaking paint on medieval glass |

Deposits on windows can include bits of grit from surrounding stonework or rust from iron bars, which could be trapped in the other dust deposits. These can easily act like an abrasive powder and scratch the glass surface. Limescale is also often present and this can leave very unsightly smear marks that may only become visible once the window has dried completely.

The safest and most effective way to clean historic windows that have no painted decoration, or where the decoration is in sound condition, is to roll (not rub) cotton buds dampened with a little de-ionised water over the glass surfaces. The slightly damp cotton fibres collect the dirt from the surface very effectively. Cotton buds of the required size can be made quite easily using bamboo skewers and raw cotton, which is available from most pharmacies. This enables the cotton buds to be rolled to suit the size of the piece of glass to be cleaned.

On unpainted glass, once the cotton bud has stopped collecting dirt, a final polish can be carried out to help the glass regain its brilliance. It is always inadvisable to polish painted glass.

In exceptional circumstances, for example where dense rust staining (previous page, bottom right) has caused unsightly discolorations on plain glazing, more abrasive methods like bristle brushes and plastic pot scourers may be used as a last resort, but only after taking professional advice.

DAMAGE CAUSED BY CLEANING

|

|

| Paint loss on 19th-century glass | |

|

|

| Rust staining before and after cleaning |

The surface of glass is surprisingly prone to scratches. It is quite wrong to assume that only diamonds are hard enough to scratch glass: wire wool, glass-fibre brushes, abrasive powders and metal tools can cause serious damage. While the damage may not be immediately visible, very small scratches can cause corrosion, particularly in medieval glass.

The removal of corrosion deposits on medieval glass is controversial, because over-cleaning can expose very fragile corroded glass surfaces. Cleaning of corroded glass should only be attempted by appropriately trained, skilled and experienced conservators, and should be done in moderation. A corroded window will never look as good as new, nor should it. Time has left its mark and that change is part of the window’s history.

Over-cleaning of windows that have fragile paint can result in severe and irreversible damage, such as the loss of painted detail, and can leave a window unreadable. Unlike paintings on canvas or paper, it is very difficult to touch-in lost glass paint.

DOS AND DON'TS

Cleaning can improve the legibility and help the long-term survival of a window, but it must be done carefully and correctly.

Do seek the advice of an expert before deciding to clean a window. It is always worth getting good advice at the start – once damage is done it cannot be undone. For churches, the local diocese can often help by recommending an advisor who specialises in stained glass. Icon, the Institute of Conservation, has a searchable online register of accredited conservators (www.conservationregister.com).

Do provide safe access. Church windows tend to be tall and are often at great height. Safe access is important; it’s not worth risking injury or worse for a clean window.

Don’t use harsh abrasive pads or household cleaners and never use acids or wire wool. Even the removal of cobwebs should only be done extremely carefully and the duster should never touch a window that contains painted stained glass.

Don’t attempt to clean medieval stained

glass if you are not a trained and experienced

stained glass conservator.

And finally: if in doubt, don’t clean.

| THE HENRY HOLIDAY WINDOWS IN ST MARY'S CHURCH, STOWTING, KENT: A CASE STUDY | |

The congregation of a small medieval parish church in Kent was delighted to learn that their church contained fine stained glass windows by Henry Holiday (1839-1927). Holiday was a Pre-Raphaelite painter, designer, sculptor and illustrator, who succeeded Edward Burne-Jones as designer of stained glass windows at Powell’s Glass Works in London in 1861 and set up his own studio in 1891. One of his best windows can be seen in Westminster Abbey. The three small windows in St Mary’s Church were so densely covered with dirt and microbial growth that no-one had given them a second glance in decades. Ivy had invaded the space between the rusting safety grilles, covering the stained glass even further. The church is situated in a deep and damp valley, and is surrounded by trees that grow very close to the building. This created a sheltered and stagnant micro-climate with very high humidity and low light levels. All of the church’s windows therefore showed dense micro-organism growth on the inside of the glass. In 2005, a survey of the stained glass windows was commissioned. It was then that the partially obscured Henry Holiday glass was identified. Close inspection revealed that the stained glass was not only covered with dirt deposits, microbial growth and ivy, but that underneath it all the delicate paintwork was in very poor condition. The long exposure to stagnant condensation and to acidic metabolic products from the micro-organisms had resulted in patchy losses of the decoration. Losses were particularly severe where water was pooling on the glass above horizontal lead profiles. The thin washes and the very fine applied skin tone were mottled with patchy losses where algal mats and moulds had invaded the surfaces. The severity of the damage, the fragility of the remaining decoration and the importance of the windows led to the relatively unusual decision to protect them with external protective glazing. This decision was not taken lightly, as it constituted a change to the building’s historic fabric. Protective glazing is more usually installed where corroded medieval stained glass needs protection from the elements. In St Mary’s, however, even with planned improvements to the heating system and some thinning out of the trees around the building, the levels of humidity were going to remain high enough to cause more damage to the already badly affected glass. The stained glass was therefore removed from the glazing grooves and taken to the conservation studio. The first treatment was the repeated application of a fine mist of an ethanol-water mixture to kill any active micro-organisms. Careful cleaning with small sable brushes was then carried out, mostly under the microscope to avoid dislodging any of the unstable paint. Loose paint flakes were consolidated with minute droplets of acrylic resin. At times it was deemed too hazardous to remove the dead micro-organisms from very flaky paint layers. In those cases they were left in place and consolidated together. |

|

The protective glazing was installed into the original glazing groove and sealed in. A condensation tray was installed at the bottom of the outer glazing, with a drainage pipe that would evacuate run-off to the exterior. After conservation, the now beautifully crisp and jewel-like Henry Holiday windows were framed with narrow bronze profiles and attached to the stonework about 50mm behind the outer glazing. Small slots at the bottom and at the top of the frames allow air to circulate around the stained glass, keeping it completely dry and free from condensation. The external appearance of these three windows has certainly changed, as the protective glazing has a much more reflective surface than the historic stained glass. The western end of the church is surrounded by trees and is little visited, however, so this change was deemed acceptable. Seen from the inside of the building, the west wall looks just as it did before, except that Henry Holiday’s figures of patriarchs and angels now shine again, and will continue to do so for a very long time to come. |

|