Cleaning Historic Ironwork for Repainting

Keith Blackney

|

||

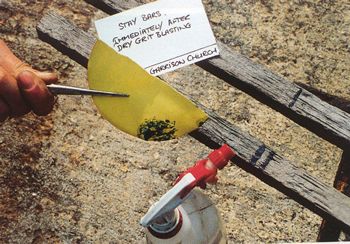

| Testing for salt contamination carried out by English Heritage on stay bars of Garrison Church, Portsmouth immediately after blast cleaning: staining on the potassium hexacyanoferrate paper indicates the presence of salts. |

Historic ironwork, including wrought iron, cast iron and steel, has almost always been coated wherever it was used externally. In addition to providing a decorative finish, the paint coating is essential to prevent corrosion.

Before carrying out major repairs to ironwork it is current usual practice to remove all corrosion products (rust) and existing coatings. This has a number of clear advantages, including facilitating repairs and removing materials which are potentially hazardous to health, while also allowing for archaeological research and revealing hidden defects.

Thorough stripping may also be required to ensure the effectiveness of the new coatings and provide the aesthetic rejuvenation which is usually desired. However, it may be unnecessary or undesirable to strip back to bare metal across the whole structure. Some corrosion products can themselves make a stable crust protecting the underlying metal. Furthermore, the paint layer itself may also contain important historical information, providing an invaluable insight into past coating technology as well as the decorative history of the metalwork itself.

The benefits of cleaning must always be weighed against the risk of accelerated decay and loss of historic material. Cleaning should not be carried out as a matter of course. In the recent restoration of Bolsover Castle, Derbyshire, for example, English Heritage discovered traces of the original painted decoration on two 17th century balcony railings. As a result it was decided to reinstate the original colour scheme and to retain as much of the existing paintwork as possible. To achieve this, the metalwork repairs targeted the areas which had corroded, avoiding collateral damage to adjacent areas of sound historic paintwork.

If stripping important metalwork of its historic coating cannot be avoided, a specialist should be brought in to take samples first, so that all the historical and archaeological information can be salvaged and recorded before it is lost forever.

COATING REMOVAL AND SURFACE PREPARATION

Severe corrosion on historic ironwork is typically localised around difficult-to-paint areas which are liable to retain moisture. Adjacent plain bars will frequently remain in perfect condition beneath a lifetime’s accumulation of paints. A range of targeted cleaning methods may provide the best way to prevent further deterioration, while avoiding unnecessary disturbance of sound paintwork and historic surface finishes. Aesthetic considerations aside, it may only be necessary to remove loose paint and corrosion in addition to any grease and dirt which will compromise the all-important adhesion and unbroken coverage of the new coating.

Appropriate surface preparation is the key to new coatings reaching their full service potential. The main methods of removing corrosion and old coatings include: hand and power tool cleaning using scrapers, wire brushes and chipping tools such as needle guns; chemical stripping; flame cleaning; air abrasive methods commonly described as shot blasting and grit blasting; high pressure water blasting. All these methods can damage ironwork and their success depends on the skill, experience and judgement of those carrying out the processes.

HAND AND POWER TOOL CLEANING

Cleaning by hand and with the aid of power tools is labour intensive and so is generally only carried out commercially as a pre-treatment to reduce the overall work cost when combined with other processes, for example to remove heavy corrosion scales before air abrasive cleaning. Yet it is surprising the speed at which some existing coatings can be removed with hammers or needle guns. However, great care must be taken to avoid bruising, distorting or, in the worst case, fracturing the metal.

CHEMICAL CLEANING

With careful selection and application of materials, chemicals offer an effective, controllable method of cleaning. A strongly alkaline sodium hydroxide solution (caustic soda) is sufficient to remove drying oil coatings. A range of proprietary products usually based around dichloromethane (methylene chloride) is used to break down oil and resin paints as well as re-liquefy vinyl and bitumen. Chemical cleaning of large areas usually involves dipping the ironwork in a solution bath while smaller areas can be treated with gels.

Acid solutions are occasionally applied to remove or stabilise corrosion but care must be exercised when using acids to avoid any potentially damaging contact with sound material. On completion of chemical treatments the metal must be thoroughly cleaned of residues which would otherwise subvert the new coating.

FLAME CLEANING

Flame cleaning, involving wire brushing while burning with an oxy-acetylene or oxy-propane torch, is sometimes used (either alone or as a pre-treatment to air abrasive and chemical cleaning) to break down thick coatings and detach heavy corrosion. However, the crystal structure of iron can be significantly affected by heat treatment, and cast iron is particularly vulnerable to fracturing. This process should only be carried out by a highly skilled operator.

DRY AIR ABRASIVE CLEANING

Air abrasive blast cleaning is now the most widely used method of surface preparation for volume work. Dry blast cleaning methods are divided into shot blasting, an automated factory process, and grit blasting, which is manually carried out in both the workshop and on site. Both methods can be adjusted to produce a range of cleanliness levels and surface profiles, which are often specified by the coatings manufacturers to achieve optimum performance of their products.

Cleaning back to the silvery grey colour of the base metal may suggest that all the contaminants have been removed. However, if left to stand uncoated, corroded areas sometimes develop a dark brown to black staining caused by environmentally-borne chemical contaminants which can remain on the metal even after cleaning. These can include chlorides introduced in the salt used on roads or in sea air, and sulphates from atmospheric pollution for example. These contaminants are hygroscopic (that is to say that they attract moisture from the atmosphere), chemically affecting the performance of the new coating and reinitiating corrosion. If not treated, these will reduce the effectiveness of even the most high performance paint systems.

HYDRO-BLASTING AND WET ABRASIVE CLEANING

Blasting methods incorporating water, such as wet grit blasting, pressurised slurry cleaning and in particular hydro-blasting (using water alone at pressures greater than 30,000psi), are effective practical methods of cleaning salt contaminated iron. The addition of water raises the possibility of rapid re-rusting (gingering). This is sometimes dealt with by adding rust inhibitors to the water. However, residual inhibitors can affect adhesion of the new coating. An alternative solution to this problem is to use paints which are tolerant to gingered surfaces. Some manufacturers even produce ‘wet blast primers’ that are designed to accept damp surfaces post wet blasting.

When applied to historic ironwork, abrasive blast cleaning may remove stable, well-adhered and often protective surface skins created during the original casting or forging, as well as removing sound coatings. Consequently, there has been a move, similar to that in masonry conservation, toward selective cleaning using equipment that can be finely adjusted, working at lower pressures often using fine blast media.

ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES

Whatever method of cleaning ironwork is chosen it is important to bear in mind that the removed material may be highly toxic. In particular, historic paint may contain leads and other heavy metals, with implications for both personal health and the environment. When planning the work, consideration must be given to the control and disposal of all waste material.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- English Heritage Research Transactions - Vol 1: Metals, James and James Ltd, London, 1998