Complying with UK Wildlife Legislation

Bats, Badgers and Newts

Nick Bonsall

|

|

| (Photo: Kurt Hahn) |

Building conservation projects run a high risk of conflict with some of the UK’s rarest animals. The traditional materials, building methods and unmanaged buildings and gardens often associated with restoration projects also provide abundant sources of food and shelter that can appeal to endangered and protected species.

This article focuses on three protected species that are frequently encountered in such contexts: badgers, bats and great crested newts. It explains how and why these animals are protected, the practical implications of that protection, and how best to anticipate and overcome the challenges these animals can present to a restoration project.

THE LEGISLATIVE FOUNDATIONS

There are many active pieces of legislation that refer to species and habitats in the UK. The key pieces of legislation are outlined below:

The Wildlife and Countryside Act (as amended) 1981 is still the major legal instrument for wildlife protection in Britain. This legislation covers the protection of a wide range of protected species and habitats and provides the legislative framework for the designation of Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSIs).

The Conservation (Natural Habitats, &c.) Regulations 1994 implement two pieces of European law and provide for the designation and protection of ‘Special Protection Areas’ (SPAs) and ‘Special Areas of Conservation’ (SACs), together with the designation of ‘European Protected Species’, which include bats and great crested newts.

The Countryside and Rights of Way (CRoW) Act 2000 compels all government departments to have regard for biodiversity when carrying out their functions. In addition, the powers of the statutory nature conservation organisation (Natural England for England) to intervene in the management of SSSIs were strengthened and steps taken to assist in prosecuting individuals breaching wildlife legislation.

The Protection of Badgers Act 1992 consolidated existing legislation on the protection of badgers. This legislation is intended to prevent the persecution of badgers. The act protects both individual badgers and their setts.

THE LEGISLATION IN PRACTICE

Bats and great crested newts are protected under both the Wildlife and Countryside Act and the Conservation (Natural Habitats, &c.) Regulations. It is an offence to intentionally or (in England and Wales) recklessly kill, injure or capture bats and great crested newts or obstruct access to, damage or destroy the resting places used by these animals.

In the case of bats, which use several resting places or roost sites throughout the year, and tend to reuse the same roosts for generations, these sites are protected whether bats are present or not. Any activity resulting in a contravention of the legislation described above would require a Natural England licence to avoid committing an offence.

Unlike bats and great crested newts, badgers are not protected because they are rare or endangered: badgers receive protection under the Protection of Badgers Act because of their history of persecution by man. It is illegal to deliberately kill, injure or take a badger, or to attempt such actions. In addition, it is an offence to intentionally or recklessly destroy a sett, obstruct access to a sett, or disturb a badger while occupying a sett; with a sett defined as ‘any structure or place which displays signs indicating current use by a badger’.

Development activities that may contravene the above legislation must be carried out under a licence granted by Natural England or the relevant statutory nature conservation organisation.

GREAT CRESTED NEWTS

The great crested newt is the largest of Britain’s three newt species and can be identified by its dark brown warty skin and bright yellow-orange belly with irregular blotches. The males also have a jagged crest along the centre of the back and tail.

Breeding takes place in ponds, although a large part of the lifespan is spent in terrestrial habitats where this species may wander as far as a kilometre from its breeding pond. Great crested newt populations often depend on having a network of ponds close together and interlinked by suitable terrestrial habitat. They are most frequently recorded in medium-sized ponds that are well vegetated but not heavily shaded. Occasional drying out is not a barrier to newt breeding and prevents colonisation by fish. The preferred terrestrial habitat is unimproved grassland, scrub and woodland.

The British population of great crested newts is one of the largest in Europe although it has suffered significant declines over the last century, largely due to the loss of habitats such as agricultural ponds. Because of recent population declines and the importance of the British populations of great crested newt in a European context, this species enjoys a high level of protection.

BADGERS

Badgers are common throughout most of Britain although they are more numerous towards the south-west with fewer in flatter arable and upland areas. Badgers can live for up to 14 years and are omnivorous, with worms making up roughly half their diet.

Signs of badger presence include: sett entrance holes, which are generally D-shaped and over 20 centimetres wide; scratch marks on trees; and latrines, which take the form of small pits about 10 centimetres deep containing slimy black faeces. The paths along which badgers travel to and from foraging areas often contain rocks and trees with rubbing marks made by the passing badgers, which may also leave tracks in wet mud and hair caught on undergrowth or fences. Evidence of badger feeding includes shallow ‘snuffle pits’ created by badgers digging for worms.

Setts have a number of classifications depending on their uses:

MAIN |

several large holes with large spoil heaps and obvious paths emerging from and between sett entrances |

|

ANNEXE |

normally less than 150m from main sett. May be in use all the time, even if the main sett is very active |

|

SUBSIDIARY |

usually at least 50m from main sett with no clear paths connecting to other setts. May be used only intermittently |

|

OUTLIER |

small amounts of spoil outside entrance holes. no clear paths connecting to other setts and used only sporadically. May be used by foxes and rabbits |

BATS

The 16 species of bat present in Britain are all relatively small and make use of echo-location to catch and feed on insects. While trees, exposed rock faces and caves were once the natural roost sites for British bats, 15 of the species now make some use of buildings, with a number now largely reliant on them for summer roosting.

Bats are often sensitive to disturbance, which can in extreme circumstances result in the death of adult bats, abandonment of young and/or colony collapse. Bats occupying summer maternity and winter hibernation roosts are particularly sensitive to disturbance and this vulnerability combined with the rarity of many bat species is the reason for the high levels of legal protection which they enjoy.

Bats, particularly the relatively widespread and versatile common and soprano pipistrelle, can roost in virtually any structure. Some buildings are particularly likely to contain bats, either because they provide a large number of possible roosting opportunities or because they are surrounded by good feeding habitats.

|

|

|

| Pipistrelle bat roost | Great crested newt (Photo: Graeme Skinner) |

PROSECUTION UNDER WILDLIFE LEGISLATION

Offences relating to protected species such as bats, great crested newts and badgers can harm more than just a company’s reputation. Each offence relating to bats, badgers or great crested newts carries a possible fine of £5,000 and six months in prison. It is also worth noting that each individual animal affected can be considered a separate offence.

It is important to remember that even with planning permission, individuals are not exempt from wildlife legislation. There are many examples of architects, demolition contractors, builders and others falling foul of the law in relation to protected species. Often offences are committed through ignorance of the relevant legislation and the responsibilities it imposes. Even those who try to ensure they comply with the law can run into difficulties when employees or subcontractors fail to understand or observe legal requirements.

On 20 June 2007 a development company was fined £2,000 with £87 costs after pleading guilty to damaging or destroying a resting place of great crested newts. The developers, aware that they had great crested newts on site, had applied for and been granted a licence by Natural England to enable ecologists to capture the newts so the development could proceed. The newts were placed in a temporary reserve while new ponds were created nearby. However, in December 2006 a contractor, instructed by a company manager to dig the new ponds, drove over special newt fencing enclosing the newt reserve and placed excavated soil on top of it. PC Andrew Long and Wildlife Management Advisors from Natural England visited the site and the prosecution followed.

BEST PRACTICE

The key to preventing surprise discoveries causing project delays and mounting costs is to take a proactive approach and assess the site early. A preliminary site assessment by a professional ecologist is a cost-effective way of highlighting any potential wildlife issues. While the planning system should flag up the requirement for survey, this cannot always be relied upon and for the majority of restoration projects commissioning a preliminary ecological assessment should be considered best practice.

|

||

| Newt hibernaculum with amphibian fencing in the background | ||

|

||

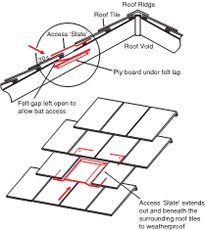

| Lead bat access slate with 20mm high access gap; diagram based on 267 x 384mm roof tiles (Illustration: Access Ecology) |

When commissioning the services of an ecologist it is important to ensure they have the right knowledge, experience and licences to properly undertake the work, and that they are members of the Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management, the ecologists’ professional body.

If the site assessment and records searches indicate that protected species may be present, or uncover records of past presence, and it is considered possible that the project may impact on these features, then a targeted survey will be required.

If protected species are confirmed on site and works are deemed likely to affect them, then a Natural England development licence will be required prior to works proceeding. An experienced ecologist should be able to develop a mitigation plan that allows the project to proceed while ensuring that the local ecology is managed properly.

Undertaking an early assessment allows for appropriate planning of surveys, which can reduce unnecessary disappointment at a later stage. There are seasonal guidelines with most species, usually timed to coincide with aspects of their behaviour such as summer or hibernation roosts in bats, breeding activity in ponds for newts or, in the case of badgers, when signs of activity are most obvious to a surveyor.

Once protected species have been confirmed on site, a range of approaches to safely working with or around the animals can be employed, depending on their number, type of activity and level of importance. The easiest approach is to avoid conflict altogether. Obviously that is not always possible and it is usually a case of adapting existing plans.

There are two key aims of any strategy. The first, mitigation, is to avoid or minimise any harm to animals during works. This can involve capture and removal or exclusion from a resting place or surrounding habitat. The second aim, compensation, is to ensure that the project does not result in any long term detrimental effect on the animals’ local population. This is typically achieved by creating alternative resting places, ensuring that populations are not isolated as a result of works, or providing compensatory habitat.

MITIGATION AND COMPENSATION

Great Crested Newts The level of mitigation

and compensation required is dependent on

the size of the population associated either

with breeding ponds or their terrestrial

habitat on or within close proximity to the

site. Mitigation will usually range from

adapting working methods to the installation

of temporary amphibian fencing and pitfall

traps. The amount of fencing and the length of

time it needs to be in place will depend on the

population size and distance from the nearest

active pond.

Compensation is typically on a two for one basis: if you remove a pond, then you must replace it with two purpose built ponds, linked to complementary habitat.

Badgers These creatures often relocate, and will sometimes use certain setts on a seasonal basis. The sett type, type of impact and alternative sites available will determine the level of mitigation and compensation required on each project. For example, an outlier in an area with lots of alternative locations which has only occasional use will be considered to hold less value than a main sett in an area with few opportunities for an alternative location, or in areas where badger persecution is high. The level of impact is also important. The following works may need to be licensed:

- using heavy machinery (usually tracked vehicles) within 30m of any sett

- using lighter machinery (usually wheeled vehicles), particularly any digging operation within 20m

- light work such as hand digging or scrub clearance within 10m.

It may be necessary to close setts down temporarily, if such works are necessary. This involves installing one-way gates over setts for a number of days prior to the commencement of works. If a sett is to be destroyed and there is no natural alternative within the clan’s territory then an artificial sett may have to be created up to six months in advance of sett closure. In either case, a licence must be obtained to ensure an offence is not committed.

Bats Mitigation for bats can be more difficult to predict and manage, as they are extremely mobile animals and need only a very small gap to access a roosting location. If it is necessary to destroy a roosting location; or if bats may be injured, killed or disturbed by operations, then excluding bats from the roost is the first option, although capture may also be necessary. Exclusion can be achieved through the fitting and monitoring of one-way gates to a roost location provided there is no other route for them to get back in. It may also be necessary to capture by hand any bats found during demolition works, for example.

Compensatory measures range from the installation of bat boxes to the creation of a purpose-built bat house. A number of measures can be utilised which aren’t necessarily expensive and can be incorporated into standard designs. Baffle boxes offer crevice-dwelling bats, like the common pipistrelle, roosting opportunities and can be incorporated into stone or brick cavity walls, roofs and roof voids. Access points can be created in a variety of often straightforward ways, for example by using gaps in pointing or under ridge tiles, or by installing lead bat-slates (illustrated near the start of this section).

AVOIDING A HOUSING CRISIS

Many of our endangered and protected species have chosen to make their homes in our homes. This can lead to conflict, especially when building repairs or alterations are carried out. However, by undertaking the appropriate planning and seeking the advice of the right ecologist, a solution can usually be found which accommodates man and beast alike.

FURTHER INFORMATION

- The Bats in Churches Project and the National Bat Helpline 0345 1300 228

- Bat Conservation Trust publishes details of ecological consultants here.

- The Chartered Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management

- Natural England

- Natural Resources Wales, Tel 0300 065 3000 (ask for the species team)

- NatureScot

- Northern Ireland Bat Group

- Northern Ireland Environment Agency Tel 028 9039 5264