Conservation Plans

Benefit or burden?

Kate Clark

There is a new buzz phrase sweeping through the world of historic building conservation: 'conservation plans'. Everyone from Heritage Lottery Fund applicants to English Heritage and the National Trust seem to be writing them. But are conservation plans the product of just another bit of bureaucracy, dreamed up to make it even more difficult to care for a historic place? Or do they simply reflect a return to the good old fashioned principle of understanding places before you conserve them, which will benefit owners and buildings alike?

WHAT IS A CONSERVATION PLAN?

|

|

| Conservation plans can be used to inform a wide range of projects from the conservation of a ship to a town and its surroundings. |

At its simplest, a conservation plan is a document which explains why a site is significant and how that significance will be retained in any future use, alteration, development or repair. The same approach can be used for historic gardens, landscapes, buildings, archaeological sites, collections or even a ship, and is particularly relevant when a site has more than one type of heritage.

Conservation plans have many different uses. The preparation of a conservation plan should be the first step in thinking about any new alterations, repairs or management proposals. It could be useful for prospective buyers or anyone planning development on an historic site. An owner will find a conservation plan particularly useful when planning the use of space and when establishing what might need listed building consent. Conservation plans also make it possible to work cumulatively - so often we waste time and money when the understanding or recording work of previous generations is lost.

Conservation plans are not new. There are already several publications on recording and analysing historic buildings and English Heritage have two useful leaflets - Development in the Historic Environment and Management Guidelines for Listed Buildings, which explain how understanding historic buildings can help developers and managers. However, the Heritage Lottery Fund found that they needed a standard approach to assessing different types of heritage, which would help to ensure that the funds they dispersed were beneficial. So, in March 1998 they published a new guidance note Conservation Plans for Historic Places. Based on the work of James Semple Kerr who developed this approach in Australia, it nevertheless reflects the fact that most UK sites are older, more complex and encompass different types of heritage. Speaking at a conference in Oxford to launch the guidance, Kerr stressed the flexibility of the approach.

However, to produce a conservation plan which is effective can take time and specialist expertise. As a result the Heritage Lottery Fund only requires a conservation plan to be submitted for large applications or where the project is particularly sensitive to change or particularly complex, such as sites in multiple ownership. Nevertheless, many other projects could not be effectively managed without one, just as a business could not be run properly without a business plan.

THE CONSERVATION PLAN PROCESS

The important thing to remember is that a conservation plan is not a list of headings but a thinking process, and one which anyone who cares for historic sites probably goes through already. The first stage involves understanding the site. Most people assume that they already do this, but the complexities of day-to-day site management means that there is rarely an opportunity to set it down systematically. So the first part of a conservation plan involves background research, drawings and the assessment of the 'physical history' of the site.

ASSESSING SIGNIFICANCE

Once the development of the place is clear, the next stage is to explain the significance of the site both in general and in terms of its different components. Here is an opportunity to explore the values we place on historic sites - be they community, social, educational or aesthetic; local, regional or national. Untangling this mosaic of values makes it much easier to think about what we are trying to achieve when we conserve a site.

VULNERABILITY

Before writing policies, it is useful to pause in order to think more about the process of change. If policies are going to help manage change you need to first understand change. The conservation plan should identify all the things that are happening to a site that make it vulnerable - including, for example, any small cumulative alterations, loss of fabric, problems with mixed ownership, conflicts between different types of heritage, the pressures of visitors, and the need for better access.

WRITING POLICIES

|

|

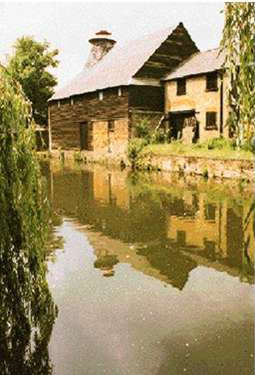

| Barber's Yard, Hertford A conservation plan (prepared by Acanthus Lawrence & Wrightson Architects) secured a difficult planning application to convert these former maltings at Old Cross Wharf, Hertford. © Acanthus Lawrence & Wrightson Architects |

Writing policies is the last stage. These should provide practical guidelines which explain how the significance of the site can be retained in any future uses, alterations, maintenance regimes or development. They can relate to individual topics - such as disabled access, restoration, lighting, setting or fabric - or to individual areas of the site. A policy on restoration might, for example, be appropriate for one part of the building and not another.

Good policies are hard to write. They can involve real debate and a good deal of consultation, which should extend to anyone who has a stake in the site, whether landowners, local authorities, local people or conservation advisers.

The final production should be a document which is well presented, easy to read and informative, but not too long (the hard work nd research can go into appendices) and one which represents as good a degree of consensus as can be achieved.

AFTER DRAFTING

Once the plan is in place, it is a relatively simple matter to draft management proposals, prioritise expenditure or begin to think about new design opportunities, each of which will benefit from the information in the plan.

This does not mean that a conservation plan is a straight-jacket which constrains future development. This is partly because a plan should be reviewed as often as necessary and also because, the better the site is understood, the more flexibility there is. The conservation plan should help to manage change intelligently, where change is appropriate, and not constrain it forever.

All of this sounds complicated and bureaucratic, and, if badly handled, it can be. But it is surprising how often a clear understanding of a site and what it needs can help in the tricky process of finding acceptable solutions for historic sites.

Recommended Reading

- Conservation Plans for Historic Places is available from the Heritage Lottery Fund (020 7591 6000)

- Copies of The Conservation Plan by James Semple Kerr are available from ICOMOS UK (020 8994 6477)

- Conservation Plans in Action: proceedings of the Oxford Conference (edited by Kate Clark and published by English Heritage in 1999) is available from English Heritage

- Further advice on commissioning and preparing plans is available from English Heritage