Counting The Cost

Richard Woolley

The advent of the ubiquitous TV property restoration programme has highlighted the all too common scenario of homeowners catapulting themselves into full scale refurbishment projects, often involving historic buildings, without a sensible budget in mind. When acquainted with these 'guestimates' the bemused expression on the face of Kevin McCloud or Sarah Beeney certainly provides good entertainment but it does highlight a situation that no client of a professional should ever find themselves in.

This is not a new phenomenon. In 1871, Edward Milner, the eminent English landscape gardener presented Lincoln Corporation with a detailed estimate for constructing the new arboretum in Lincoln. However, by the time of the opening ceremony in August 1872, costs had risen from an estimated £4,207 to £8,000, an eye-watering 90 per cent increase. Not surprisingly, this did not go down too well with the committee.

| THE

DEAN'S EYE WINDOW, LINCOLN CATHEDRAL A UNIQUE PROJECT |

The restoration of this important medieval window was completed late in 2005 and was unveiled by the Prince of Wales in May 2006. The complete restoration of a large rose window is an extremely rare event and historic cost data is non-existent. Also the project was supported by English Heritage's Cathedral Grants Scheme and, as such, each phase of work had to be carefully scheduled out and costed. The success of the project relied on a highly experienced professional team of advisers (architect, engineer and setting out specialist) along with an exceptionally skilled direct works department. Each element, be it stone or glass, was broken down into component parts of labour, plant and materials. This allowed accurate composite rates to be created for each carved stone and panel of glass. This immensely complex scheme was completed on budget and on time. |

|

Estimating the cost of a construction project should be a core skill of any quantity surveyor (QS). In an ideal world the client consults with his or her architect, who may then prepare basic sketch drawings and/or a brief scope of works. At this point the client should be interested to find out if his or her exciting scheme can actually be procured for a manageable cost, and a QS should be introduced into the mix. The whole process ought to be a relatively straightforward exercise: client defines requirements; architect interprets requirements and produces scope of works; QS then prices scope of works and hands estimate to client in a suitably detailed format. Once the client has absorbed the bad news, the scheme content is refined until an appropriate budget is established and, hopefully, the project comes to fruition with the oft-used phrase 'on time and on budget' being sung from the rooftops upon completion.

Sadly the process is rarely that simple. There are many issues which stand in the way of a successful estimate and these factors are even more apparent when estimating for work involving historic buildings and structures. Get the estimate too high and your client will not thank you later on when he could have afforded a larger extension or more high level repairs. Get it too low and, after a tense tender opening exercise, you face the unenviable task of telling your client that his scheme is potentially dead in the water.

So what problems might arise?

SOME SPECIFIC DIFFICULTIES

Accessibility How do you calculate the integrity of a stone string course when it is 25m above ground level and can only be seen somewhat obliquely from a nearby window? A lower string course on the same building may appear to be relatively sound but is the upper course the same? Binoculars may assist but nothing compares to standing on a scaffold and tapping away at a piece of stone. For a tall building such as a cathedral or church the only way of accessing high level stonework is by abseiling or, in certain cases, via a cherry picker. These investigations are not free and not always viable.

Health and safety concerns A fire-damaged or badly eroded structure could pose significant risks with the distinct possibility that some areas may be totally out of bounds. Alternatively an empty building may have boarded up windows to prevent vandalism, creating a very gloomy interior. Finally, a 200 year old mill building may be ankle deep in guano. Leptospirosis is not something you want to take home with you after a hard day's site visit.

Hidden structures/elements It is common to find ferrous fixings buried within stone ashlar walls, window tracery, columns, pediments and other structures. The composition of thick walls in ancient buildings can sometimes only be guessed at. Sloping plastered ceilings to roof slopes could be hiding extensive timber decay. A series of cracks in an old brick gable wall could indicate merely a detachment of a later brick skin away from the older timber frame behind or a much more serious structural failure. Changes to the structure could have occurred many moons ago with no documentation to hand. An ancient building can prove to be a minefield for the unwary.

Scarcity of pricing information A number of 'industry standard' pricing books are produced each year which are widely used by the surveying profession. These are predominately geared towards new build or refurbishment works using relatively modern building materials. It is possible to extract certain rates but these are to be used with great caution. For example a current pricing book indicates a rate of £160/m2 for Westmorland green slates laid to diminishing courses, while the writer has received recent tenders with rates of £190/m2, a difference of almost 20 per cent. Similarly, a pricing book suggests that the raking out and re-pointing of decayed joints in stonework would be £26/m2 while a recent tender for wholesale re-pointing to a church has been priced at £54/m2. Reliance on pricing books alone could therefore be disastrous. For many common elements found in historic buildings it is not possible to find pricing information at all, including, for example, wrought ironwork, giltwork and ornate carved stonework.

Specialisms Certain structures involve highly specialised materials and techniques. It is not practical to retain a database of current pricing information for all elements that might be encountered. Repairs to early concrete framed structures, restoration of 18th century wallpaper or repairs to 19th century laminated beams are all typical examples.

Listing status A building may be of great historic value with Grade I or II* status or may be denoted as a scheduled ancient monument. This will necessitate consultations with a whole plethora of organisations, the ramifications of which will not be known until after the production of the initial estimate.

VAT and grants These two categories represent additional costs and cost-offsets respectively. VAT for historic buildings is a moving feast and one which needs careful handling to ensure the best outcome for the client. Establishing the value of any grant aid available can be even more difficult and usually the final amount will not be known until long after the initial estimate.

|

|

|

HISTORIC

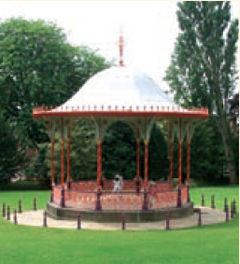

GARDEN STRUCTURE For the refurbishment and restoration of a Victorian iron bandstand (above), an investigative study was carried out before the tender stage, and this established a budget for repairs and the subsequent tender information. However, once on site and after scaffolding and opening up works, it became apparent that the majority of the cast iron column heads were badly cracked. There was no way of knowing this from earlier inspections. After much discussion it was agreed that the bandstand would be dismantled and repaired off site in workshop conditions. The consequence was that the costs escalated significantly. Was this overspend preventable? Possibly not. A full opening up exercise would have involved scaffolding costs, specialist analysis, protection/security measures and the problems of making the structure weathertight again. It is not possible to second guess all eventualities. In a case such as this, the contingency figure has to be relied on. |

|

ENSURING THE PREPARATION OF A SUCCESFUL ESTIMATE

Recognition of the pitfalls likely to be encountered is half the battle. The estimator must then plan for the task ahead and adopt some, if not all, of the following:

Clear brief This is essential whether or not the building is historic and if the architect or client does not provide one, then the QS has the duty of tactfully winkling this out. For example, where is the line to be drawn on repairs? Are aesthetics as important as weatherproofing and structural repairs? It is also important that the client's maximum budget is established at this early stage.

Drawn information Old plans and elevations are useful, if they can be found. If not then the architect should be encouraged to produce rudimentary sketches to allow the production of basic quantities at the very least.

Measured quantities It is very difficult to prepare a satisfactory estimate based on unit rates only (that is to say, costs per square metre, based on the gross internal floor area). These can be used in exceptional circumstances but are unlikely to produce an estimate of acceptable accuracy. Basic quantities of wall, floor and roof areas along with the numbering of doors and windows are all very useful and allow for some certainty in the pricing.

Rates database As discussed earlier, industry standard rates are not collated and published. The Directorate of Ancient Monuments & Historic Buildings (the precursor to English Heritage) produced an estimating guide for directly employed labour up until the 1980s although this was somewhat limited in scope. It is therefore vital that the estimator creates and maintains a database of rates using cost information from previously completed conservation projects.

Site visit This would seem an obvious requirement, but a request to prepare an estimate using two or three e-mailed photographs is not unheard of. A site visit by the QS in the company of the architect and other professionals is much more constructive and informative. In this digital age a building can be comprehensively photographed during a visit and these images can prove to be extremely useful when back at the office.

Adequate fee Calculating the cost with any degree of reliability takes time, particularly where conservation work is concerned, and an adequate estimate is unlikely to be produced without an adequate fee. No client or funding body should ever rely on an estimate produced on a negligible fee or, even worse, no fee at all.

Hazardous materials The incidence of the use of asbestos in historic buildings is unfortunately fairly common. If at all possible, the client should be persuaded to pay for a Type 2 survey before any works commence on site. This is for two primary reasons: firstly, to estimate the costs of removal of contaminated materials and, secondly and possibly more importantly, to avoid lengthy delays (and therefore increased costs) if works are held up on site later on.

Involvement of key professionals and specialists In addition to the architect, certain projects will require assistance from other professionals such as structural engineers and mechanical and electrical consultants. If further specialisms are involved and the client has sufficient monies, budgetary advice should be sought from suitable firms. In certain circumstances it may also be useful to consult with a main contractor with appropriate skills and experience.

Investigations If possible, some opening up should be organised. If not possible due to the need for listed building consent, then opening up at a later date should be arranged and the estimate updated at that point in time.

Access Safe access to high level roofs and walls is extremely useful and should be built into the client's fee budget.

Timescale The process should not be rushed. Adequate time should be given to allow for information gathering and any necessary consultations.

Price risk analysis It would be very easy to assume the worst case and build an estimate up to an untenable level. Nevertheless a scheme involving an historic building should have a healthy contingency. Inevitably there will be surprises, no matter how much investigative work is carried out. A minimum allowance of 10 per cent should be included. Specific provisional sums should also be identified when warranted by the nature or condition of the building.

Experience Last but not least, the surveyor carrying out the estimate should be well versed in the historic world. As with many business practices there is no substitute for experience.

With the potential obstacles identified and a careful checklist of procedures adopted, it should be eminently possible to produce a clear and robust early stage estimate to allow the client and his team to make critical decisions regarding the viability of a scheme. Specific risk areas can be acknowledged and changes can be introduced before too much detailed design work is undertaken and the die is cast.