Rewiring 'A Temple to High Victorian Technology'

Sarah Schmitz and Caroline Rawson

|

|

| Cragside today(photo: Gavin Duthie) |

In 1971, Mark Girouard compiled a list of the best-preserved Victorian country houses to survive in the UK and identified those which would be well worth the National Trust acquiring. Six years later the Trust acquired the property ranked top of that list - Cragside in Rothbury, Northumberland. By then, the need to replace the electrical wiring system in the house - highlighted by a statutory electrical inspection - was already long overdue. However it was not the only priority, and it was to require substantial investment and much careful thought. As a result, the current programme is only the most recent in a series of necessary projects to maintain the fabric of the building and its services. The first was to repair the leaking roof.

Cragside is a house and a garden, and rather more than that. It was the home of Sir William George Armstrong (1810-1900), later Lord Armstrong. Through scientific innovation and entrepreneurial skill he achieved immense wealth in the manufacture of hydraulic machines and armaments. This 'palace of a modern magician' parallels his achievement and derives from it. Many of Armstrong's innovations were tried at or adapted for Cragside. The house itself began as a modest holiday home in 1863 and was transformed by architect Richard Norman Shaw between 1869 and 1884 into an imposing mansion. Now Grade I listed, the house contains some of Shaw's best preserved and most original work, a splendid example of his English vernacular style. Of national importance too is its collection of furnishings, furniture (much designed especially for Cragside), and fine and decorative arts, including work by many other outstanding designers of the age, such as the Hancock brothers, and William Morris and Company. However, it is probably for its technical advances that the house is most important. In 1880, Cragside became the first in the world to be lit by hydro-electricity, and the first to be lit by Joseph Swan's newly invented incandescent light bulbs. At this time, it also had hot and cold running water, central heating, telephones, fire alarms, a hydraulic passenger lift and a Turkish bath suite. Other examples of Armstrong's ingenuity in the field of hydraulics and engineering are scattered outside on the estate. It can be said that Cragside was the place where modern living began.

|

|

| Cragside with newly installed light fittings as illustrated in The Graphic, 2 April 1881 |

To power his hydro-electric and hydraulic projects, Armstrong had the Blackburn burn dammed in the hills above Cragside, creating new lakes. Water from two of the lakes dropped a vertical distance of 103 metres (340 ft) to the power house creating the necessary water pressure. Here he installed a Vortex turbine made in Kendal and a Siemens dynamo which, in 1878, were used to illuminate his paintings in the Cragside's gallery. However, the arc light then available produced far too much light for the purpose, it smoked and it was not safe. It was not until the modern light bulb was invented that it was possible to create what Swan described as the 'first proper installation'. It seems that this consisted of two independently switched circuits, one for all the upstairs lights and one for downstairs, so all the lights in the rooms on a circuit would have been either on or off at the same time. Traces of this circuit are evident throughout the house and are being steadily uncovered and documented by the Trust's resident archaeologist, David Reed of Bernicia Archaeology.

The power supply for this early installation was improved by the introduction of portable batteries in 1883 which were installed to store electricity generated in periods of low demand for use later, and by the completion of a new power house in 1886. This housed a purpose made turbine and generator which was capable of producing more than 10KW of electricity. Nevertheless, it was still entirely dependent on water supply, and capacity was soon outstripped by demand from the growing number of light fittings. At times it was impossible to run both upstairs and downstairs lights at the same time. So in 1895 hydro-electric generation was supplemented by a gas-powered engine which was used to drive a second generator. The house was rewired with a new parallel circuit by Drake & Goreham of London. Although still a DC current, the result was a great improvement, enabling individual fittings to be independently switched for the first time at Cragside.

|

|

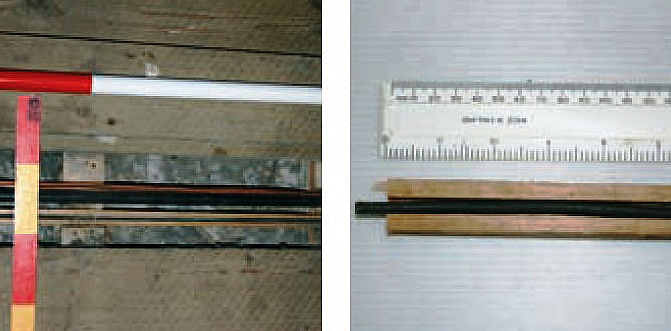

| Wire and timber casing from Armstrong's earliest installation (Photo: Bernicia Archaeology) |

Some further changes to the wiring have taken place since the 19th century, in particular some modifications had been made when the current had changed from DC to AC, and there had been a partial refit in the 1940s. However, under the floorboards and inside the walls there remained a hotchpotch of circuits, conduits and channels, some of enormous historic interest.

Early in the new millennium, the time had finally come to look at rewiring what is clearly one of the largest and most complex houses in the Trust's care. By then, health and safety issues for a building welcoming over 100,000 visitors every year, had become uppermost in the Trust's mind, not least because there was never a guarantee that using a light switch would not give you a shock!

The rewiring of the 100 room mansion is now an integral part of the 'Regenerating Cragside' project - a programme of capital works launched at the beginning of the millennium with the objective of assuring the estate's future.

|

| Timber casing and fluted capping from the Drake & Goreham installation (Photo: Bernicia Archaeology) |

PLANNING

Before the alterations could take place, all aspects of the requirements and their consequences had to be carefully considered, and English Heritage was involved from the outset. Most importantly the scale of the project had to be confirmed. It was decided that a full lighting and power rewire was necessary, as were new security and conservation heating systems. The mains supply would have to be upgraded, and a new sub-station built.

As with any building project undertaken by the National Trust, fundamental principles were set early in the planning stages to protect the fabric and appearance of what is an extremely important Victorian home. These being that:

- light fittings, accessories and switches should remain the same in appearance despite being refurbished to meet current fire and safety regulations

- historical electrical services such as cables dating from the earliest phase of hydroelectrical power should be retained in situ because of the high historic value of the early technology

- the new cabling should follow original cable routes wherever possible to avoid altering or weakening the fabric of the building by, for example, notching joists or chasing plasterwork

- any new discoveries made relating to the history of the house should be thoroughly recorded with photographs and plans and should only be removed if absolutely necessary.

|

|

| Length of timber casing and capping |

It was decided that MICC (mineral insulated copper cable) should be used because of its high resistance to mechanical damage, excellent fire resistance properties and extended serviceable life span. All cabling is to be hidden under floorboards, in roof spaces or behind existing trunking to avoid altering the house's appearance.

The large Victorian kitchen provided an interesting conundrum because its inaccessible concrete ceiling and tiled walls meant that cables could not be hidden. It was agreed between the contractor and the National Trust that cables should be drawn through existing surface mounted steel conduit. This seemed an agreeable compromise, re-using an historic element for the purpose for which it was originally intended.

The selection of new sockets, switches and heaters has also provoked an interesting debate, and is a typical example of the choices which regularly have to be made in sympathy with the building. The appearance of the interiors could so easily be compromised by the use of stark, white, obviously modern fittings but making them appear historical creates ethical questions. The compromise of dark coloured, modern looking fittings was reached because they were 'honest' but unobtrusive. For such decisions having a National Trust Curator of Interiors occasionally available on site has proved invaluable.

|

|

| One of Armstrong's original light fittings on a lion finial on the main staircase |

PREPARATORY WORK

An important element was the packing away of the contents of the house, some 10,000 objects. Almost 80 per cent of Cragside's collection is original to the house, much of it having belonged to Lord Armstrong himself. It contains a rich array of artwork, furniture, workaday Victorian items and personal family belongings. Taking conservation, security and cost into consideration, storing the collection on site was the best course of action. A dedicated storage area was created within the house in which to protect them, and furniture, paintings, textiles, natural history specimens, ceramics and ephemera were then wrapped, labelled and placed in storage by the house team.

In addition, the house itself contains wonderful examples of both Victorian decorative interiors and elements of the later Arts and Crafts Movement. Original wallpapers, carpets, tiling, sculpture and wood carving fill the house and all had to be adequately protected from damage during the re-wire, as had structural elements such as doorways and tiled corridors.

The programme of the project followed three separate phases with the electricians working within only one area or phase of the house at a time. This meant that at least part of the house retained electrical power, allowing access to light, heat and power (vital for tea making in particular). The delicate and important nature of the collection meant that such factors had to be thoroughly considered when planning on-site storage.

|

|

| Channel cut into wood beneath fitting showing how it was originally wired |

Special expertise provided through project posts proved important, not only during the tightly-scheduled packing and protection stages but also later in the main phase of the project. Two project joiners worked ahead of the electricians, preparing rooms by carefully lifting floorboards and removing skirting boards which they will later reinstate. A project conservator was on site at all times liasing with the contractors and being responsible for the day-today protection of the house and its contents. A project archaeologist was also present to record existing historical services which were exposed when floorboards were lifted and to catalogue any interesting finds discovered during the course of the works.

The existing house team who maintain the building when it is open to the public were also on site at all times to provide expert knowledge and work alongside the electricians, ensuring the re-wire went as smoothly as possible.

Seizing the opportunity of the house being closed to the public, the house team were able to clean areas which are normally inaccessible, the ten ton marble fireplace constructed in the drawing room in honour of the visit of the Prince of Wales to Cragside in 1884 being a prime example. The closure of the house has also meant that staff could accept various relevant training opportunities and then utilise their new skills such as the conservation and cleaning of wallpaper.

Volunteers who act as room stewards when the house is open have also been very busy, giving talks to visitors at the front of the house and assisting the staff with their cleaning and inventory work.

LIGHT AT THE END OF THE TUNNEL

At the time of writing this article, work in 40 rooms is almost complete with around 60 remaining in the next phase still to commence. The handover of completed areas from the contractors to the House Team has begun, and the work of thoroughly cleaning and reinstating the show rooms is just beginning, as is the relocation of everything in storage to allow access to the third phase of the building.

It seems appropriate to mention the many other considerations which have to be made when rewiring an historic building. The 'project team', which meets monthly, includes the property manager, project administrator, curator, conservators, building manager, and the marketing and communications officer. The closure of the house could have had a dramatically negative impact on the Cragside estate which remains open to visitors. However, creating new attractions, advising the general public of the house closure and keeping them informed of the progress has been a vital part of the project and has meant that many people continue to visit and enjoy the estate.

In April 2007 when the house finally reopens after 18 months of intensive work, if the Project has been a success in conservation terms, it will appear relatively unchanged to the visitor's eye. Some might find this frustrating but the house's fabric, its contents and visitors will all benefit, something Lord Armstrong himself would no doubt have approved.

Please call 01669 620333 or email cragside@nationaltrust.org.uk for information on opening times, admission prices and facilities at Cragside.