The Easy Wins

A strategic approach to improving energy efficiency in traditional homes

Rachel Coxcoon

|

||

| Tightly packed Georgian housing in Bath: intrinsically sustainable design with a low ratio of external envelope to interior |

The past three years have seen an explosion in retrofit activity, not least because of the heavily promoted (but now defunct) Green Deal programme. External wall insulation in particular has been promoted heavily by government as the number of unfilled cavities and lofts has diminished and policymakers’ attention has turned to the ‘hard to treat’ sector, which includes almost all buildings of traditional construction.[1]

However, the list of approved measures under the Green Deal did not include some of the simplest available interventions. An unfortunate side-effect of this omission has been to focus public awareness on the more expensive, disruptive and (for traditional buildings) potentially damaging[2] measures at the expense of easier, cheaper and less disruptive ones.

Growth in demand for these more expensive measures has also created opportunities for less skilled operatives to move into this area of work. This has increased the risk of poorly applied external wall insulation systems being carried out by general building firms without the specialist knowledge needed to specify each system to the bespoke needs of the house in question. This is especially true of traditional buildings, which function differently to modern ones, particularly with regard to how air and moisture move around them. Modern buildings rely on a high level of air and moisture tightness, and the design aim is to create a sealed envelope that keeps most moisture out through the use of moisture-resistant materials and finishes. Excess moisture such as that generated in bathrooms and kitchens is typically expelled mechanically via extraction fans or, at the very least, trickle ventilation in windows.

Applying an external render that adds to the already impermeable design can significantly improve some more modern buildings in terms of thermal performance. By contrast, traditional homes (partly because they pre-date the technical ability to achieve moisture tightness) have tended to work with flows of moisture. Damp from the ground, driving rain and occupant use would have travelled through the walls and occupants principally relied on sunshine, wind, heating and ventilation through windows, chimneys and draughts in order to keep the building at an acceptable equilibrium.

Since many traditional homes were not originally constructed with an internal bathroom, plumbing or central heating, and because the idea of taking a daily bath or shower would have seemed like madness to many of our predecessors, the amount of moisture generated daily by a household would have been much lower. Most traditional homes now have these features, so the fabric of those buildings must deal with far higher levels of moisture than in the past.

|

|||

| The Centre for Sustainable Energy’s Love Your Old Home booklet (2014) | |||

|

|||

| Damp and mould caused by poor external wall insulation (Photo: CSE) | |||

When coupled with the application of impermeable insulation materials and insufficient ventilation, this can have disastrous consequences. Moisture that would previously have travelled through the walls is now trapped inside. Mould and mildew can build up and eventually cause damage to the fabric. It is therefore vital that those living in traditionally constructed homes are asking potential contractors the right questions about the system that will be used and the way that excess moisture will be dealt with.

Less well documented, but perhaps of equal concern, is the effect that new external finishes can have on the historic significance of many traditional buildings. The Centre for Sustainable Energy (CSE) has run a local energy-efficiency advice service in the Bristol and Somerset area for more than 20 years, including home visits for complex cases. It is regularly called upon to advise householders in traditional homes on how to improve efficiency (mainly by reducing heat loss). Three things are becoming increasingly clear to CSE advisers as they deliver these services:

1 Residents of traditional homes often have little knowledge of the construction techniques used in them, or the way in which moisture moves through the building. This is compounded by a tendency to believe (perhaps because of the marketing techniques of modern house-builders) that moisture movement in or through walls should be resisted at all costs, and that it is a sign of an underlying problem with the house.

2 Very few people understand the meaning of the term ‘significance’ when applied to historic properties. Householders typically fail to distinguish between impacts on historic significance and impacts on the physical fabric of the building when proposing change. They are not the same; one can be present without the other – for example poorly fitted insulation which increases condensation could lead to physical damage in the first instance by creating a build-up of damp between a stone wall and internal wood panelling. If the wood panelling then has to be removed as a result, then not only is there physical damage but ultimately loss of historic significance as well. However, it is also possible to damage only the historic significance of a building, for example by obscuring decorative brickwork with external wall insulation where this measure has no detrimental effect on the physical fabric of the building. Conservation officers may well object to proposed retrofit simply because it will damage historic significance, a concept that the householder often finds vague and elusive, without causing actual physical harm to the building.

3 It is very common for householders to want to make changes based on a desire for a particular product or measure (such as double glazing), rather than a desire to see a particular outcome (such as reducing draughts), often because they have received some sort of marketing literature about the product in question.

Particularly where buildings are listed or in a conservation area, these three factors are the source of a great deal of conflict with local authority conservation and planning teams who expect greater justification for the installation of potentially damaging measures than many householders are prepared to give. More guidance is also becoming available to support local authorities in framing their decisions. The forthcoming Historic England conservation research report The Sustainable Use of Energy in Traditional Dwellings (authored by CSE, 2017) is targeted at local authority planning and conservation officers and explores how to use legislation and policy to guide decision-making.

Where the building is neither listed nor in a conservation area, there is no such oversight from local authority experts, and these three factors (alone or in combination) mean that many householders are making changes to their properties that can be hugely damaging to their value, both from a heritage point of view and also in physical terms.

|

LEAST INVASIVE |

INVASIVE |

MOST INVASIVE |

WALLS |

Gap filling |

Internal solid wall insulation |

External solid wall insulation |

|

|

Insulating within depth of timber frame |

|

ROOFS |

Loft hatch insulation |

Rafter insulation |

|

Loft insulation (unheated loft) |

Flat roof insulation |

||

FLOORS |

Gap filling and floor coverings |

Under-floor insulation (suspended floor) |

Under-floor insulation (solid floor) |

Under-floor heating |

|||

Over-floor insulation |

|||

WINDOWS |

Thermal curtains and blinds |

Refurbishing and draught-proofing original windows |

|

Refurbishing or reinstating |

Framed secondary glazing |

Replacing non-original or badly damaged original windows with timber double glazing or slim-line timber double glazing |

|

DOORS |

Door draught-proofing |

|

New high-performance |

Door refurbishment |

|||

Creating a draught lobby |

|||

CHIMNEYS |

|

Chimney blocking |

|

To try to cut through some of this potential for conflict, the Centre for Sustainable Energy produced a booklet titled Love Your Old Home in 2014. The booklet guides homeowners through a four-step process to evaluate what makes their home historically significant, and what that means for the types of energy efficiency improvements they could make. CSE is also working with the National Trust on guidance for applying for and securing consent for traditional home retrofit, which is primarily aimed at helping residents in protected buildings to understand how to apply for consent for appropriate measures, but will also be a useful resource for local authority officers. An accompanying online resource is also being developed to provide technical advice on a range of retrofit measures

THE ENERGY HIERARCHY

The energy hierarchy is an excellent framework for thinking through the range of possible changes:

- first reduce energy demand (for example by changing behaviour in the home)

- then ensure energy is used as efficiently as possible

- then look at generating the remaining energy needs from renewable sources.

This approach ensures that the ‘low-hanging fruit’ are chosen first, which often yields comparable benefits to more complex, expensive, or harder-to-implement measures.

In a heritage dwelling, the energy hierarchy should be considered within a ‘whole house’ approach – that is, understanding the home as a system, and systematically thinking through whether changes made to some elements or functions will impact on others. For example, draught-proofing will decrease the movement of air in the home, so consider fitting controlled ventilation. Chapter 2 of Warmer Bath, ‘Deciding what to do’, explores how to reduce energy use and improve energy efficiency in a traditional dwelling, and compares measures to each other in terms of cost and carbon cost-effectiveness.

Further guidance on the appropriate choice of measures will be available from a forthcoming Historic England advice note, which CSE has helped to develop and which will set out good practice on the sustainable energy retrofit of traditional dwellings.

|

|

|

| Most of the heat loss through this Georgian sash window was eliminated simply by draught-stripping. The restored shutters and heavy curtains also enabled the window to be insulated after dark. Draught-stripping on the meeting rail of the lower sash (shown open in the middle illustration and closed on the right), neatly eliminating a significant source of draughts. (Photos: Centre for Sustainable Energy) | ||

EASY WINS

With reference to the above, it is crucial that retrofit plans start with the desired outcome, not with a specific measure. It can be useful to rank desired outcomes because this can also guide the best approach. Examples of desired outcomes are:

- a warmer home

- reduced running costs

- increased market value.

Thinking about a Georgian house with sizeable windows against this list of desired outcomes, the measure that might initially spring to mind could be double glazing. But the key question is always the same: ‘Is there something simpler, less invasive, and more cost-effective that I can do first?’

In this case, there is almost certainly a cheaper, less invasive way to achieve all three outcomes. Replacing original Georgian windows with modern double glazing is unlikely to have a positive impact on the market value of the home in any case, since original features are so highly prized. It is also unlikely to be acceptable in heritage terms if the building is protected in any way. It may be that timber, slim-line double glazing units could be acceptable, but these are likely to be astronomically expensive. However, a combination of other measures might achieve the same desired outcomes with less harm (for example draught-proofing the original windows, in combination with fitting thermal blinds and curtains with the installation of secondary glazing and the renovation of existing internal shutters).

Ideally, energy-saving measures should also contribute to conserving the building’s significance, including undertaking necessary remedial and maintenance work, and might even enhance it by emphasising historic features and the ways in which they illustrate the building’s history and use.

CHOOSING APPROPRIATE MEASURES

Behaviour change is always the cheapest measure, and should always be considered first. Better control over heating and lighting systems can sometimes be expensive but can reap rewards in the long run (fitting more efficient boilers, heating controls and timing systems). The imminent roll-out of smart meters bridges the behaviour and control themes, and ‘queue jumping’ is sometimes possible so householders are encouraged to contact their utility provider to see whether they can have a smart meter installed. Daily interaction with the data from a smart meter has been shown to alter energy-use behaviour and cut energy costs without any other measures being implemented.

Beyond behaviour change and better controls, we move into the realms of physical changes to the home. Breaking down the home into its constituent elements, the types of interventions that can be deployed can be ranked from least to most invasive (green to red) which, in general terms, also means least to most expensive.

|

||

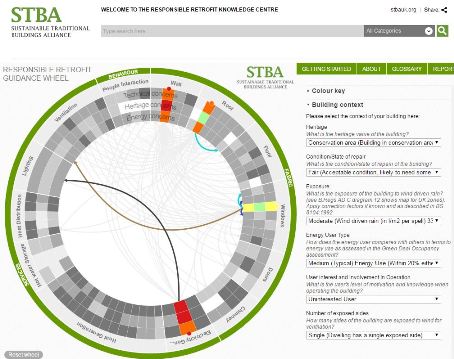

| Produced by the Sustainable Traditional Buildings Alliance, the Responsible Retrofit Guidance Wheel helps users to evaluate how a range of measures might interact with each other and what risks they could pose to a given building’s physical fabric and historic significance. (Image: STBA, see:http://www.responsible-retrofit.org/wheel/ ) | ||

If all the measures coloured green in the table above were deployed (alongside behaviour change and better controls), the likely energy savings and comfort improvements would be significant. In terms of value for money they would be likely to cost less in total than a single red measure in the table.

Detailed guidance on how a range of measures can interact with each other can be found in the excellent Responsible Retrofit Guidance Wheel (left), produced by the Sustainable Traditional Buildings Alliance. This allows the user to select a range of measures and consider how they might interact with each other and what the risks to both the physical fabric and historic significance of the building might be.

Fuel poverty levels are higher in traditional homes than in the wider housing stock, the costs of energy are rising almost inexorably, national retrofit policy is seemingly in disarray following the collapse of the Green Deal, and huge cuts to local authority budgets mean that conservation specialists are thin on the ground. It has never been more important to ensure that householders have access to useful guidance on making the right choices on how to make traditional buildings more energy efficient.

The UK’s heritage housing stock is an irreplaceable resource, the value of which is slowly and irrevocably being eroded through the application of badly planned retrofit projects. While it is clear that the joint challenges of climate change, fuel poverty and energy security must be tackled, it should not be at the expense of our national heritage. A range of useful and comprehensive guidance resources now exists, many of which are referenced below – getting the message out to those who live in traditional homes on how best to make them fit for the future is now the key challenge.

Further Information

• W Anderson and J Robinson, Warmer Bath: A Guide to Improving the Energy Efficiency of Traditional Homes in the City of Bath, Bath Preservation Trust/Centre for Sustainable Energy, 2011

• Department of Energy & Climate Change, Smart Meters: A Guide, 2013

• Oxford City Council, Heritage and Energy Efficiency Tool

• D Pickles et al, Energy Efficiency and Historic Buildings: Application of Part L of the Building Regulations to Historic and Traditionally Constructed Buildings, English Heritage, Swindon, 2011

• Sustainable Traditional Buildings Alliance, Responsible Retrofit Guidance Wheel