In the Footsteps of AR Powys

An unusual timber conservation case study

Lynne Humphries

|

|

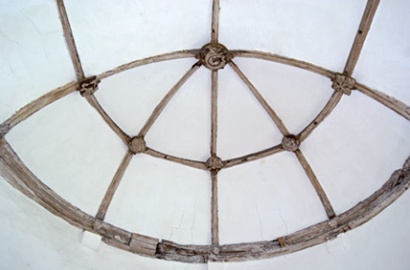

| The east end of St Andrew’s, Winterborne Tomson: the oak barrel-vaulted ceiling probably dates from the 15th or early 16th century, while the box pews, screen, pulpit and altar rail are early 18th century. |

The Church of St Andrew, in Winterborne Tomson, Dorset, is a small Norman church, unaltered in its plan since the early 12th century. It still retains the original single cell form with its curved (apsidal) end. The oak barrel-vaulted roof probably dates from the late 15th or early 16th century and is believed to be unique in that it spans the curve of the apse. All of the interior timberwork, including the box pews, screen, pulpit and altar rails, is early 18th century. The gallery is also of this date but incorporates parts of the medieval screen and rood loft.

By the early 20th century St Andrew’s had fallen into a very poor state of repair, and when the architect AR Powys rescued the church in the 1920s it was almost derelict. Powys was by then the secretary of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, and a pioneer of conservation. Founded by William Morris 40 years earlier, the SPAB was born out of a reaction to the insensitive ‘restoration’ of churches in the pursuit of an idealised vision of the past. Here Powys sought to preserve as much of the surviving fabric as possible and he carried out a remarkably sensitive programme of repairs, conserving original material that would, at that time, usually have been discarded. He and his wife are buried in the churchyard. A plaque in the church, beautifully cut by Reynolds Stone, commemorates Powys’ work.

A programme of conservation at St Andrew’s was recently funded by The Churches Conservation Trust, which has cared for the church since 1974. The aim was to preserve the interior decorative timberwork which was suffering from an ongoing infestation of deathwatch beetle. The project brief included the consolidation and conservation of the moulded wall plate (the horizontal length of timber on which roof timbers rest), the roof bosses on the barrel-vaulted ceiling and the west gallery front, as well as the repair of the west door. Given the scope and complexity of the work, this article focuses on the conservation of its eight finely carved roof bosses.

PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATION

As with all conservation projects, the first step was to examine and record the areas to be dealt with alongside an overall appraisal of the church. The extreme fragility of the wall plate and bosses was immediately evident and several other issues were highlighted that posed difficult questions and generated intense debate. Much of this centred on the repairs that the decorative timber elements had undergone over the years: which repairs needed replacing and which should be retained? What justification was there for removing repairs that were functioning but unsightly? And, most unusually of all: should some of the repairs that were no longer functioning be retained on the grounds that they were revolutionary for their time and therefore historically significant in their own right?

|

||

| Conserved bosses over the apse |

Amazingly, Powys had managed to retain fabric that was so riddled with deathwatch beetle holes that little or no structural integrity remained. The bosses had all been removed, filled with large quantities of wax (probably bees wax), screwed to timber mounting boards with protruding tabs and then screwed back into position on the ceiling ribs. Additional timbers had been nailed to some of the backboards to offer additional support. These hinted at the original form of the bosses.

These repairs and others, such as the timber supports for the gallery panels, were visible and ‘honest’, in the spirit of the SPAB’s philosophy, easily differentiated from the original fabric. However, in many places they were very crude and in several instances the additional timbers supporting the bosses detracted from their original lines.

Several phases of repair had taken place since Powys’ astonishing interventions, and these too had a bearing on the programme of works:

- A new beam had been incorporated behind the moulded wall plate so the current repairs to the wall plate did not need to provide structural support other than to the immediate surrounding area.

- A filler had been applied to the deteriorated exposed face of the wall plate which had discoloured to a vivid orange. This was not only unsightly, but more significantly prevented localised consolidation behind the face. However, it was not deemed to be damaging in itself despite providing little or no support.

- Attempts at treatment of the deathwatch beetle had resulted in an ugly rash of black plastic injection nodules across the timberwork.

- The wall plate had been crudely repaired with both soft and hardwood indents, which corresponded poorly, if at all, to the original profile of the moulding.

THE CHALLENGE

|

|

| Much of the timber was riddled with the flight holes of deathwatch beetle, and some of the bosses were so far gone that there were more voids than timber. (Photo: Brian Ridout) | |

|

|

| One of the best preserved bosses after conservation, showing four beakheads arranged in a square. To save the fine carvings in the 1920s, AR Powys had consolidated the timber using wax and mounted each boss on a board before fixing it back into its original location. |

The repairs carried out by AR Powys were probably unprecedented in their approach and arguably deserved as much care and respect as the building’s earlier historic fabric. The conservation approach and the specific methods used were shaped both by the condition of the elements and by the historical importance of his repairs.

The most challenging conservation issue was how to consolidate the very friable decorative timber elements, which had been damaged by deathwatch beetle to such an extent that in many areas more void than timber remained. The wax which had been applied to the face of the bosses in large quantities, as a consolidant and filler, probably as part of Powys’ original specification, now offered little or no support to the decaying timber behind, and in many areas the deathwatch beetle had continued to eat through the wax. The greatest difficulty was gaining access to the underlying timber to consolidate sufficiently to save the elements.

As it was obvious that the deathwatch beetle infestation, present prior to Powys’ work, had continued, the first step was to deal with the cause of the problems, then to establish the severity of the damage and which elements were structurally compromised.

DAMP AND DECAY

The principal source of damp penetration was via flaws in the roof covering, and specifically in a bituminous felt underlay introduced when the roof was last re-laid. As this is not vapour permeable, condensation which collects on the underside cannot escape, making the adjacent timber surfaces damp. Local flaws were dealt with during the contract, and the CCT hopes to relay the roof on a vapour permeable membrane in 2010-11.

Treatment of the deathwatch beetle was investigated and after extensive talks with damp and timber decay consultant Brian Ridout, of Ridout Associates, chemical treatment was ruled out. This type of treatment had not succeeded in the past and there was no reason to suspect that it would be successful in the future. The most appropriate treatment would be to install light traps in time for the next mating season. Any remaining deathwatch beetle population will continue to decline and will eventually die out as long as the church remains free of damp.

CONSERVING THE BOSSES

Consideration was given to further consolidating the bosses with wax, in keeping with Powys’ work, not least because this would avoid the need for removing the applied wax. As with all consolidation of highly friable and absorbent materials, no consolidant measure is truly reversible, and removing the wax posed significant problems. However, it was decided that further application of wax could not penetrate the remaining timber sufficiently to consolidate it without employing a total immersion method, such as that used with PEG (polyethylene glycol). This would have altered the appearance to a greater extent than other consolidation methods and would have been more costly. Furthermore, the wax had been crudely applied; in many instances it concealed the original carved face of the boss and in all cases it disfigured the carvings, making the original design difficult to read. It had also attracted much dust and debris. Trials were therefore proposed to find a satisfactory compromise, including an appropriate method for removing the wax from the bosses, a suitable consolidant to strengthen the friable timber, and appropriate support fillers for the different areas.

|

|

| Boss from east end after wax removal and consolidation. Support fill has been applied to protect fragile areas, and the crude timber supports have been reduced to follow the original profile of the boss. | |

|

|

| Central boss during conservation. Most of the wax has been removed and friable areas consolidated. A section of white Plastazote has been inserted for support and to fill voids around the perimeter. | |

|

|

| Above: the interior of the church looking west and, right, the central boss in situ before conservation: the wax conceals the friable state of the timber, the back plate is visibly protruding behind the boss, and one of the fixing tabs is damaged. |

Wax removal: the most suitable method was found to be mechanical, using scalpels or small spatulas and fine surgical tools. The timber was in such a fragile condition that it was necessary to consolidate at every stage of the removal process.

Timber consolidation: Paraloid B72 acrylic resin in acetone applied in varying strengths was found to be the most suitable consolidant for the timber generally. Paraloid B72 in acetone was used to re-adhere dislodged fragments.

Surface support fillers: it was necessary to design several different fillers, and their strength had to be then adjusted as required by controlling the ratio of bulking agent according to the condition of the adjacent timber to which it was being applied. For superficial crevices either Plextol B500 acrylic resin or Paraloid B72 in acetone were used, both mixed with spruce wood flour, polyfilla and pigments.

Void fillers: for the larger crevices between the bosses and back boards Plastazote LD45, a closed-cell cross-linked polyethylene foam, was chosen. Clearly non-traditional and therefore a controversial choice, its use provoked considerable debate. It was selected because it is lightweight, chemically inert, easily blended in, and flexible so that it does not apply new stresses to the surrounding fabric. Importantly, it can easily be removed in the future as it was attached to the backboard and not the bosses.

The first boss on the north elevation was in the weakest condition. It predominantly consisted of dust and frass (the powdery waste produced by wood-boring insects). The decision was made not to remove the frass but to consolidate immediately, in situ, with Paraloid B72, with the frass inadvertently serving as a bulking agent. No attempt was made to remove any wax in situ, as there was no remaining structural integrity in the timber. The boss was supported while the three screws were gradually loosened and the boss could be safely lifted down and placed in a box to be transported to the workshop.

The remaining seven bosses were removed from the ribs in the same manner and placed face up in boxes on their backboards. They were then transported to the workshop where the wax was carefully removed by hand as described above. The bosses were consolidated continually during this process with Paraloid B72. After consolidation from the face, all the bosses were turned to allow access to the sides and rear. They were supported in boxes of dry sand with a separating membrane and consolidant was carefully applied to the rear by injection. Much of the rear side of the bosses had disintegrated entirely leaving a large void between the back board and remaining original carved face.

The applied sections of timber were removed or reduced with sharp chisels where required, to either allow access to the rear of the bosses, or to enable the bosses to be read as originally intended. Filler was applied to support fragile areas but no attempt was made to restore the original profile.

Next, the Plastazote LD45 foam filler was cut to shape and inserted around the perimeter gaps to give additional lightweight support to the fragile and vulnerable edges, to improve the visual integrity of the bosses, and to avoid dust and dirt entering. It was set back slightly from the edge and adhered to the backboard with Paraloid B72. A neutral colour was applied to the Plastazote with pigments in Paraloid B72.

The backboards were then lightly cleaned to remove accumulated dirt and debris and any necessary repairs to the backboards and their fixing tabs were carried out. Original fixings and iron nails were retained and pencil markings from previous interventions were not disturbed. Timber inserts from past phases of work were only removed or reduced in size where this was deemed necessary for access or visual integrity.

The largest of the bosses situated at the apex of the ceiling was conserved using the same methods as for the others. However, when the wax was removed, crude timber inserts were exposed. These were removed on the grounds that they protruded above the original line of the carving, preventing effective consolidation of the fragile central areas.

On completion, a very thin coat of limewash was applied to the deteriorated faces of the bosses to improve their visual harmony. This decision was based on the evidence of early applications of a white limewash.

Following conservation of the wall plate and ribs, the bosses were refixed using stainless steel screws in the original fixing holes. Where possible, the conservators avoided packing holes with rawl plugs or fibre plugs to avoid additional stress. The bright steel was toned down by sandpapering the surface and applying a brown wash.

THE WALL PLATE, RIBS AND GALLERY

The wall plate and to a slightly lesser extent the ribs had also suffered extensively from deathwatch beetle attack. Many areas had lost the carved face entirely leaving little more than a mass of flight holes. Black plastic injection nodules, relating to an earlier treatment of the deathwatch beetle infestation, had been inserted around the full length of the wall plate at approximately 30cm intervals and were also present in some of the lower sections of the ribs. As these were both unsightly and redundant they were carefully drilled out avoiding further damage to the timber and filled to blend in with surrounding timberwork.

|

|

|||

| Sections of wall plate from the south elevation before and after conservation. The orange filler and black plastic injection nodules were removed but all timber inserts were retained despite their crudeness. The conserved wall plate was lightly limewashed. In many respects the methods of conservation highlighted the beetle holes and fragile state of the timber work but it was thought that this did not detract from the charm of the church. | ||||

The orange filler applied along the length of the carved wall plate and gallery was not considered to be damaging in itself, but it prevented the consolidant reaching the depths required. Consequently, the decision was taken to remove it as far as possible without causing further loss of original material. Trials carried out suggested the following solutions:

Filler removal: Acetone applied by brush or syringe softened the filler sufficiently to allow manual removal using small spatulas and scalpels. The injection of acetone behind the filler enabled the filler to come away from the decayed timber without further damage or loss. Consolidation was required before, during and after the removal process.

The filler was softened sufficiently by the application by brush and injection of acetone to allow gradual removal without applying pressure to the delicate and fragile timber. Consolidation of the timber with Paraloid B72 was carried out during and after the filler removal process.

Removal of the filler, as with the wax on the bosses, revealed the stark extent of the damage caused by the death watch beetle. The decision was taken not to conceal this decay again but to keep these areas exposed offering support fills to weak and vulnerable areas only. The visual contrast between the carved surfaces and the decayed surfaces ironically resulted in enhancing the original work.

Surface support fillers: Plextol B500 or Paraloid B72 as used on the bosses was also used as the binder more generally, but with different fillers, adjusted to control strength and texture. For the door, spruce wood flour and pigments were added. For the deeper voids of the wall plate and gallery, glass microspheres were used.

Void fillers: to fill the large voids between the timbers of the wall plate and the gallery, lime putty and chalk (chalk dust and nodules) were mixed with the local Masters Pit sand (supplied by Rose of Jericho) and goat hair. Jute twine dipped in a lime putty slurry was inserted as a packer for deep voids.

Support fillers were applied to vulnerable areas of the wall plate and ribs, and horizontal voids between elements were pointed with the lime putty and chalk mortar mix. The timber indents from earlier repairs and any exposed decayed surfaces were then treated with a thin application of limewash to match adjacent areas.

SOMETHING OLD, SOMETHING NEW

Throughout the programme of works at St Andrew’s, both past and present conservation approaches were discussed and debated. It is not surprising to find that the range of technology and materials available to the conservator has increased significantly since the work of Powys in the 1920s. However, many of the proprietary products now on the market for the consolidation of timber cannot be regarded as tried and tested in the context of historic building conservation. Ultimately, a carefully considered balance of traditional and new materials and techniques was required.

Perhaps more surprising is the change in practical approach to the philosophy of conservation which is evident here. The inserts made by Powys were designed to be readily distinguished from the original, but some of these distracted from the lines of the original. Modern practice is to make alterations that are less harsh and more sympathetic to the original. The result has clearly enhanced the simple charm of this beautiful church and our approach should offer plenty of food for thought for future timber conservation projects.