Perfected by the Hand of Taste

Funerary Monuments at St Patrick's Cathedral, Armagh

James Stevens Curl

|

||

| The Church of Ireland (Anglican) Cathedral of St Patrick, Armagh (Photo: St Patrick’s Cathedral, all other photos: James Stevens Curl) |

In 445AD, around a century and a half before St Augustine arrived in Canterbury, Patrick (Patricius, Pátraic, or Pádraig) founded within a hill-fort at Armagh (Ard-macha or Ard-magha) the church which he decreed should be pre-eminent in Ireland. Centuries later, in 1261, Máel Pátraic Ó Scanaill was elected Archbishop of Armagh, an appointment ratified later that year by Pope Urban IV, and, in 1265, on the site which St Patrick had chosen, he began work on a new cathedral-church, the plan of which seems to have partially survived in the present cruciform structure.

Ó Scanaill’s model was probably the church at Mellifont in modern County Louth, and the style appears to have been First Pointed Gothic with lancet windows, traces of which are still visible in the south transept. The body of the nave and aisles owes its origins to works carried out under Archbishop Milo Sweteman from c1365, but the building as a whole underwent draconian re-edifying in 1834-41 under Lewis Nockalls Cottingham (1787-1847), who encased it in alien red sandstone. Cottingham’s only concession to Irishness can be found in the crenellations of the crossing-tower. In 1838, aspects of Cottingham’s interventions were denounced in certain quarters for destroying the ‘associations which the antiquity of the building did and should excite, by making it a regular English parish church… even the reddish sandstone… has an English look…’.[1] There is a certain amount of truth in this criticism, even though Cottingham uncovered some genuine medieval fabric and was himself a pioneer of the Gothic Revival.

The Church of Ireland (Anglican) Cathedral of St Patrick, Armagh, would not rank highly architecturally among the larger churches in these islands, but it is of considerable historical interest, and contains a collection of funerary monuments of national artistic and historical importance, a fact recognised in the pages of the Ulster Gazette, which noted (19 September 1885) that the ‘memorial sculptures… are ranked among the best work of its kind in Europe’. Only three of these can be described and illustrated in a short article, but they are of superb quality and deserve to be better known.

THE DRELINCOURT MONUMENT

Situated in the north aisle, this is distinguished for the reclining figure carved by the Antwerp-born John Michael Rysbrack (1694-1770). The young Rysbrack executed funerary monuments designed by the Scots architect James Gibbs (1682-1754), and it was not long before he was also realising designs by William Kent (c1685-1748). With contacts such as these, Rysbrack could hardly have gone wrong, and it was with an architect, W Coleburne of London, that he created one of Armagh’s most spectacular funerary monuments, a Baroque work of singular importance because it was one of the first in these islands with which he was involved.

|

||

| Baroque Drelincourt monument in the north aisle | ||

The monument commemorates Paris-born Peter (Pierre) Drelincourt (1644-1722), who graduated MA from Trinity College in 1681. Like many Huguenots, he did very well in his new country, and in his case this was largely due to the patronage from 1679 of James Butler (12th Earl and later 1st Duke of Ormond), who actively promoted Huguenot immigration. Drelincourt remained high in the Duke’s esteem and was ‘the most successful embodiment’ of Ormond’s ‘policy of assimilating’ [2] Huguenots into Irish society. In 1691 he was appointed Dean and Rector of Armagh as well as Rector of Clonfeacle: thus he became one of the wealthier clergy of the period, a happy position that enabled him to marry Mary Morris, daughter of Peter Morris (or Maurice), briefly Dean of Derry in 1690.

James Stuart’s account of the Drelincourt monument includes the following description:

This elegant piece of sculpture was executed by the famous M. Rysbrack, and is a noble specimen of his talents. The dean is represented as recumbent. His attitude is graceful and dignified, and the several parts of the figure harmoniously combine in producing a pleasing unity of effect. The drapery is simply disposed, and so arranged as to excite in the mind of the spectator the idea of a perfect symmetry of form, slightly veiled beneath its flowing folds. The features are strongly expressive of intelligence, mildness and benevolence, and were peculiarly admired, by Dr. Drelincourt’s contemporaries, for the strong resemblance which they bore to the original. The whole monument is, indeed, an exquisite piece of workmanship, perfected by the hand of Taste, usque ad unguem.[3] On the front of the sarcophagus [is an] appropriate inscription.[4]

Behind the figure of Drelincourt is a tall slab of marble on which is carved a fulsome Latin inscription giving an account of Drelincourt’s history and background and mentioning the Ormond connection, among much else.

THE STUART MONUMENT

This is now in the north aisle, and is a distinguished work of Francis Leggatt Chantrey (1781-1841). Born in Jordanthorpe, Norton, near Sheffield, [5] young Chantrey had only a rudimentary education, but around 1808 he determined to concentrate on sculpture and moved permanently to London. He soon achieved fame, and King George III sat for him in 1809: this royal patronage marked the start of an illustrious and prolific professional life. In 1809 too, he married his cousin, Mary Anne Wale, who brought a substantial dowry to the marriage, and his career took off at a spectacular pace. Chantrey’s standing led King William IV to confer a knighthood on him in 1835, and when he died the sculptor left a considerable fortune.

|

||

| Neo-Classical Stuart monument in the north aisle |

His splendid monument in Armagh, a serene masterpiece of Neo-Classicism, commemorates William Stuart (1755-1822), fifth son of John Stuart (3rd Earl of Bute and prime minister from 1761 to 1763) and his wife, Mary Wortley Montagu (only daughter of Edward Wortley Montagu and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, the celebrated letter-writer, who introduced inoculation against smallpox to Britain in 1721). William Stuart was ordained in 1779, and 1793 saw his appointment as Bishop of St David’s. His homilies were greatly admired by King George III, and in July 1800 he received a request from the King to consider assumption to the office of Primate of Ireland and was duly translated to the See of Armagh.

As archbishop, Stuart was indiscreetly critical of his fellow-bishops, largely because of their failure to promote education. He chaired the Irish Board of Education Inquiry and under his ægis that organisation issued 14 influential reports between 1809 and 1813. He also oversaw a poorly conceived ‘restoration’ and re-ordering of the cathedral, which had to be comprehensively unpicked and remedied some 25 years later. Stuart had an unfortunate and premature death owing to a mix-up between a bottle of embrocation and one of laudanum.

As far as is known, Chantrey carved three memorials that were erected in Ireland. Apart from that to Archbishop Stuart, he produced the funerary monuments of John James Maxwell (2nd Earl of Farnham) in Urney Parish Church, Cavan (1826), and of Major-General Sir Denis Pack in Kilkenny Cathedral (1828). Stuart’s monument was ordered in 1824 and completed in 1826: it cost a thousand guineas, then a very considerable sum. In addition, there was the expense of transporting it to Armagh, where it was originally erected in June 1827. Rennison recorded that ‘Mr Chantrey’s Man’ had arrived to do the work,[6] and that a place for the monument had been ‘fixed on’.[7]

The place selected was in the south aisle, so the figure of the archbishop originally faced west. Chantrey’s completed work attracted some criticism: the ‘stiffness of the arm or rather shoulder which adjoins the wall’ was noted, for example.[8] William Makepeace Thackeray, however, visited Armagh in 1842 when collecting material for his Irish Sketch Book and singled out the ‘beautiful’ Stuart monument for praise, finding the cathedral as a whole ‘as neat and trim as a lady’s drawing-room’.[9]

Primate Stuart had presided over some very curious alterations in 1802, including the placing of an altar at the west end of the nave,[10] but by the late 1830s such travesties of ecclesiastical arrangements were seen as unacceptable. However, the Cathedral Board Vestry Meetings also reveal that there was some re-ordering and shifting of positions of monuments in the 1880s.[11] In 1886 [12] Alexander James Beresford Beresford Hope (1820-87, politician, author, ecclesiologist, and architectural pundit) wrote a letter recommending the appointment of the architect Richard Herbert Carpenter (1841-93, son of the early Gothic Revivalist Richard Cromwell Carpenter [1812-55])[13] to carry out new works of restoration and re-ordering. Carpenter was at that time in partnership with Benjamin Ingelow (d1925), and Beresford Hope described him as a ‘man full of genius and taste’.[14] Their work at Armagh is outlined in a report published in 1886,[15] although they are vague about what they did to the monuments. That they carried out some moves is clear from a spoof letter published in the Ulster Gazette in July 1888 deploring the fact that Primate Stuart was now facing east, having been removed from the ‘south isle’ where he ‘looked at the children’ of his people as they ‘entered’ the church.

|

||

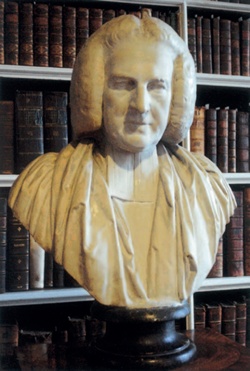

| Bust of Archbishop Robinson in his great library at Armagh, presiding over the volumes he collected |

The Stuart monument has several parallels in other sculptures by Chantrey showing kneeling bishops in their cathedrals: one is that commemorating Bishop Brownlow North in Winchester (1825), and others are the memorials to Bishop Shute Barrington in Durham (1832-3) and to Bishop Henry Ryder in Lichfield (1837). Archbishop Stuart is shown wearing a clerical wig, but Shute Barrington is regarded as the first bishop to discard this accessory and is depicted bald-headed. Stuart’s monument is one of Chantrey’s finest and most noble achievements: it deserves to be better known, not least for its austere dignity. Executed in marble, the entire architectural background to the kneeling figure represents an Antique sarcophagus, complete with pitched lid, but we only see the ‘end’ of this sarcophagus, enhanced and set off by a black background.

THE ROBINSON MONUMENT

This last section will describe a fine monument in the south aisle, differing in style from the previous memorials, and, in its own way, also of considerable interest. It is that commemorating one of the most important prelates of the 18th century, Richard Robinson (1708-94, Archbishop of Armagh from 1765 and 1st Baron Rokeby from 1777).

Robinson was more celebrated as an architectural patron than for the cure of souls. The historian, Anthony Malcolmson, however, has taken a dim view of him, although he recognised that he had ‘many positive achievements to his credit as a builder and improver’, an ‘administrator’ at diocesan, metropolitan, and primatial levels, a legislator, and ‘an enforcer of lapsed ecclesiastical standards’.[16]

Robinson was responsible for encouraging improvements to the See of Armagh, including the building of the Archiepiscopal Palace (1770), the Public Library (c1771, one of the most agreeable of all library-buildings in these islands), and the Royal School, Armagh (1774), all three to designs by Thomas Cooley (1742-84). Robinson also promoted the general beautification of his archiepiscopal city. In short, Robinson has been held to have been a munificent man, intelligent and with refined tastes (as attested by his collection of books in the library he founded), and his sensitive yet firm features spoke eloquently, to some, of his culture and intellect.

|

||

| The monument to Primate Robinson in the south aisle, bust by Joseph Nollekens and the rest of the ensemble by John Bacon II |

Robinson’s funerary monument is a handsome work by two artists. The prelate’s bust appears to be by Joseph Nollekens (1737-1823), the foremost portrait-sculptor working in Britain in the period 1776-1815: born in London, he was the son of Joseph Francis Nollekens (1702-48), a painter from Antwerp who had settled in the capital in 1733. Young Nollekens was apprenticed to the sculptor Peter Scheemakers (1691-1781, also a native of Antwerp). The rest of the monument, however, is by John Bacon II (1777-1859, the first distinguished British sculptor of the industrial revolution) and dates from 1802. Bacon’s monument to Robinson is signed and dated, and consists of a simple inscription on white marble flanked by fluted strips capped by blocks in the centre of each of which is a circular motif, and above the cornice is the archbishop’s mitre, a bound volume, and a plinth on which the bust is set. Nollekens’ creation is set off against a dark-grey panel with a pointed top (an early nod to Gothic, perhaps), and over the primate’s head, set on the panel, is a shield with the Robinson Achievements of Arms.

Bacon the Younger inherited one of the most flourishing sculpture businesses in London at the time, and had a phenomenal number of commissions. He made use of designs by his father (suitably adapted) on several occasions and he also drew upon works by other sculptors for themes and motifs. His work, especially in its architectural treatment, often had Neo-Classical tendencies and his Armagh monument is an example of this.

Nollekens’ portrait-busts often displayed great authority: his sculptured head of Robinson is a noble work, serene and commanding, dignified, and with considerable presence. The fact that he had worked for some time in Rome shows in his creations, for he was clearly well-versed in the Classical style, and when he made funerary sculpture a major activity of his London workshop, he often depended on death-masks as the bases for his portrait-work. There is no evidence, however, that his bust of the primate was derived from a death-mask, for the finished work shows a man who is very much alive, in control, and impressive in every way, and it is probable it was made around the time Nollekens was carving the memorial to Robinson’s brother for Rokeby in 1777, in other words when the archbishop would have been aged 59, or thereabouts, and in his prime.

Taken as a whole, the Robinson monument is impressive. It is an excellent example of its period, when Neo-Classicism was in the ascendant, Baroque was no longer fashionable, yet the ultra-severity of slightly later works was not generally in vogue.

~~~

Recommended Reading |

|

|

|

Notes |

|

| 1 Rennison, 1838; see also Stokes, 1868, for

observations on excessive restoration 2 McGuire & Quinn, iii, p461 3 ‘Even to a hair’, meaning ‘perfectly’ (an expression used by sculptors who tested the smoothness of their work with their finger-nails) 4 Stuart, pp518-19 5 The Church of St James, Norton, contains a memorial tablet to Chantrey, who was buried in the churchyard to the south-west of the church. 6 Rennison, letter from Kelly to the then primate, 1827 7 Beresford, pp56-7; I am indebted to archivist Thirza Mulder for drawing this to my attention. 8 Ibid 9 Thackeray, xviii, pp319-20 10 Myles, p92 11 Minutes of Vestry Meetings (Cathedral Board), p002468030 LE 1.4, p124 12 Rennison, quoting letter of 11 July 1886 13 RC Carpenter, with others, had designed important furnishings for Beresford Hope at Christ Church, Kilndown, Kent, 1840-45. 14 Rennison, 1880-89 quoting letter of 11 July 1886 15 Carpenter and Ingelow, passim 16 Malcolmson, p11 |

|